We once came across the body of a stray sheep in the woods. The starved animal lay on its side in bunch grass—bloated and out of recognition with its legs straight out. Adi was devastated by the death of this loyal working creature that gave its wool so willingly. Using our hands, fingers and a flat stone, we buried it in the softest dirt we could find. As Adi’s palms were blistered and raw, I licked the blood and dirt from his hands. Later, back at the Berghof, Adi sent an SS patrol to place a marker on the little sheep’s grave. I soaked Adi’s palms in warm salt water, jealous of the water drops that lingered in each dented vee of his hand.

Handing me a pansy, he’d say, “When I see a flower, my hand sees it first.” That’s how much he misses those painting days when he wouldn’t sketch people. He was right to concentrate on blossoms that could never betray him.

If we came across wildflowers he didn’t know, we’d give them names. I would start: “This is a Russian loser.” He’d add, “Rommelous Vainous.” And we’d laugh.

From painting, he learned about politics. The space around an object is there for the taking. Space. Untouched. Vulnerable. Brush in his hand, he could be anything. Paint couldn’t see him, but he could see paint. There was joy in sending one line running into the next—lines like soldiers, one depending on the other. He’d command strokes to look long when they were short, approach at one angle, then withdraw, make things brighter when they were dull. He moved trees from place to place. Those artist hands painted words even when he gave speeches, his gestures drawn so fully and colorfully. “Paintings are such splendid lies,” said this once poor artist who lived in an attic room on Schleissheimerstrasse.

Blondi’s bark would intercept any further thoughts on art. She’s always interrupting, something my two little Scotties never do. Smelling of dried urine, she oozes spittle on her jowls. She pivots in place like an idiot toy, turning around exactly seven times before lying down. Her mouth hangs open and her tongue droops to the side like a lecherous old prostitute. With a funny crate-nose, cold and wet, she also has wiry hair that makes her look bulky. She has chronic problems with irritated anal glands, a condition that gives off an awful oily smell. Because she’s always biting at imaginary insects like a horse chewing on its flank, the base of her tail is getting thin. Even when I divert her with a bone, she eats stones. Hot spots, areas of moist irritated skin, are on her back and hips—Adi calls them “Berghof sores” and treats them with iodine. Most irritating of all, she’s such a stupid pacifist she’ll sleep right next to a cow or cat if you let her.

The click of her toenails on the Bunker concrete drives me mad. She’s a poor sleeper and has nightmares, stomping her feet in her dreams. When they both emerge from Adi’s room, she half-wags her tail, a kind of salute that’s suppose to impress me. I’d be more impressed to see her tail out stiff and her body stuffed hanging on the wall next to Frederick the Great.

The three of us walk from room to room in this concrete—Blondi with her large tongue hanging out covered with dust. With Adi she neither snarls, snaps, whimpers nor splays her legs to spread ugly toes in a web when she walks as she does with me. Believing in sled dog rations, he feeds her fatty meat, forgiving a creature its inability to survive on vegetables. “That girl has stools that weigh almost two pounds,” he says triumphantly as I watch her squirm on the concrete rubbing worms out from her rear.

I dream about the old days—days above ground when the smell of dogs was not pungent. And that wonderful time Adi let me go to Berlin. Not to walk beside him. My visits were only “privately” official. I understood that. The fat housewives of Berlin know nothing about love outside their houses and chubby little brats. It was Goebbels who talked the Führer into including me, especially for that one great historic moment of cleansing German literature. “She can’t miss it,” Goebbels urged. Adi finally agreed, his consent influenced by the headaches I helped to lessen by rubbing warm oil on his forehead and placing liver slices over his eyes at night. Though grateful to me, he worried that a liver essence might have entered his retina.

He never insists that meat be verboten at his dinner table for a warrior who fights for Germany needs a belly full of bloody beef to attack. His generals eat like pigs. Adi reports to them, “Do we not have in common with Blondi a four-chambered heart? Don’t we both come from an egg? Don’t we both drink the same water?” Adi encourages women in every kitchen in Germany to mount a sign in runic script over the stove: “German Shepherds Divide Us from the French.”

At a staff meeting, he gave lessons to his officers who were fishermen on how to detach the hook without injuring the fish’s jaw so the creature could be released back into the water. He wanted no fish to be slaughtered.

That important day in Berlin, I carried a torch along with 30,000 students as we marched down Unter den Linden. Smart enough to tuck a pair of walking shoes in my bag, I wore them even though I desperately wanted to stroll in my laced black calf-high heels. This was fashionable Berlin. With sensible clogs, I’d be like a student. I’ve always looked young. Swimming and walking give me flawless skin. So I appeared quite youthful. With a wreath of heather on my head, I wore my full white dirndl skirt and blue sweater.

Before the main building of Berlin University, we sang patriotic songs as the SS threw books out the library windows and then dragged oxcarts of volumes like so many Joan of Arcs through the streets to be burned… 20,000 books to be incinerated not far from the statues of Alexander and Wilhelm Von Humboldt. A charming blond boy put a mangled book on Alexander’s stone head. How imaginative these young people were, how proud I was to be in their midst. If they only knew they were brushing up against the very woman who lives with their God.

In the square before the Opera House, “Gobbespierre” strolled proudly to the pyre. There was excited pushing and shoving but nothing out of control. For a small man, Goebbels’ hands are surprisingly broad and he angled them like a raft surfing through the thick slush of the common man. I couldn’t detect his limp. Maybe it was his posture or the handsome young men beside him in their SA plus-four knickers and brown shirts.

Goebbels likes to make important speeches at night when people aren’t quite so alert after a hard day’s work, when he can use blazing torchlights to whip them into a frenzied patriotism.

One student began to chant, “Optimus magister bonus liber.” Goebbels shouted along with him, “The best teacher is a good book. Get rid of slimy teachers.” I found it humorous that Josef Goebbels, who wrote a book that couldn’t get published, was now about to destroy all the published ones.

“Whenever I hear the word culture, I reach for my gun. Das Knaben Wunderhorn, old German folk songs that belong to our country, have no author’s name. That’s what we should honor.” Goebbels’ voice was shrill and pierced my ear like a stab. Nobody is more a lover of culture than Goebbels, but he was speaking for those who can’t handle words and ideas wisely, like people who can’t save money and are constantly in debt. Somebody has to make sure pennies as well as words are prudently parceled out.

“Better to turn a Nazi into a great artist than to turn a great artist into a Nazi,” Goebbels shouted. An open trailer rolled behind him carrying airplane wings marked with dark black crosses. There was cheering.

I felt the warmth of a young student pushing up against me. He wore an old postman’s jacket and began to rub his legs against mine, enjoying his own kind of camaraderie. He whispered his name in my ear: “Karl.”

“It’s necessary to execute devious books,” Karl told me. He had a high forehead and beady eyes without lashes.

“And the greatest book is Kampf.”

“You can hardly call that a book.” Karl’s hands, with the long tapering fingers of a good Aryan, were rubbing my back.

“Then what?” I asked indignantly.

“Experience. Didn’t all the medievalists turn from books to the earth itself? Like Copernicus—looking at the sun. The Führer’s book is the sun.”

I was happy I’d listened to Goebbels’ long-winded musings about Copernicus. “Ah, yes. The sun.”

“Like each of these.” Karl’s hands went under my sweater and squeezed my breasts as I leaned against his reedy chest.

“Do you mean—the life force?”

“The milk that is life’s knowledge,” he said. “A true Nietzsche thing unto itself.”

Göring explained to me that the Nietzchean Uberman was free from God. “To believe in nothing?” I asked proudly, showing off to Karl.

“To believe in prediction. Which comes from nothing. The Führer is at the center of experimental learning. He has used all technical application to predict the master race.” Karl took his hands away, and they hung long and lonely at his side.

“And just what laboratory is conducting these experiments for the Führer?” I asked shyly, knowing full well that unlike this young student, I could ask my question to the Führer himself.

“Ghettos.”

“Are you speaking of resettlement camps?” I asked.

“With a shaved head you can spot one instantly. Their skull gives them away. For science has provided the Führer a supreme view of the world. He’s dissecting inferiors for a brute understanding with the caveat of lösung. Solution.”

Karl’s thumbs moved to my armpit.

“Are they in discomfort?” I asked.

“Who?”

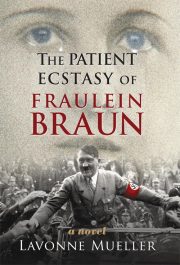

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.