When she returned home, husband Josef was away in Dresden. There was nothing to do but rub against the pointed frame edges of 32 Dürer sketches Josef had obtained from Poland. Dürer, Magda said happily, was not impotent.

19

NO, MAGDA IS NOT MY RIVAL. Nor are all the fat wives of his generals who coo over him, bring him dishes of cookies and play the piano for him after dinner. And I understand and accept his passion for Germany. I’m mostly jealous of Blondi.

Bormann gave Blondi to Adi. Why, why didn’t I give Adi a dog, a polite dog that would know its place, a mutt that didn’t try to imitate Adi’s speeches by rolling her eyes in wonder and dilating her snout.

A mutt that didn’t put paws over her ears, especially when I’m talking. And she lounges on the map table and is so lazy that Adi has to pick her up like a brick and move her out of the way.

Journalists wrote about Blondi. Sonnets and poems were composed about her, letters from various kennels arrived, tributes from breeders. Philosophical notes on German shepherds appeared in the daily paper. Once a woman wrote to ask if she could baptize her daughter “Blondi.” Bormann replied to such correspondence by sending glossy pictures of the Führer walking with Blondi at his side.

Having my two adorable little Scotties, Negus and Stasi, I certainly don’t dislike dogs. I had pets as a child—lizards, cats, a bird. And I was fond of my uncle’s pony that he used for his cart to haul lumber. I get along fine with Blondi. I have to. She has no reason to be jealous of me. She has Adi whenever she wants even while sleeping and loudly hiccupping at the foot of his bed every night.

“Adi, why can’t I sleep at the foot of your bed?” I was teasing, but as strange as it sounds, I’d really love to.

“Blondi is not only my watchdog, her higher temperature keeps my feet warm.”

“I think I could achieve that myself.”

Adi looks at me annoyed. With Blondi, there is no sarcasm. “You would do well to study her discipline.”

“I’m disciplined. Don’t I cut your toenails once a week?”

“You are saving them?” he asks earnestly.

“In a bank. On your side table. You know that.”

“Yes. Yes. Make sure you don’t default.”

“I won’t. I’m faithful as an old dog.”

Arching an eyebrow, he looks at me to observe even the slightest sign of mockery. He won’t stand for that. Blondi is a friend more valuable to him now that his generals are so erratic.

“Make sure your hands are clean.”

“Ja.” I scrub my hands with soap and alcohol as he’s fearful of germs and even more concerned about an epidemic in the Bunker. Although we don’t have proper bathtubs, we have plenty of water.

“And be very sterile with Blondi’s pups, too.”

“Ja. I don’t wish to wear fleas.”

Adi just stared sternly at me, not wanting to speak and acknowledge my disrespect.

Blondi had five babies in March. After giving birth, she began licking her two closest tits and drinking her own milk along with the pups. I’m not looking forward to nurturing five more silly creatures.

Adi asked Magda and me to put the infant pups between our breasts as it’s the fastest and easiest way to keep the little ones warm after birth. Cradled in our bras, they nestled and nipped restlessly like moving jaws. When I was not available, Magda could accommodate all five. As the five sucked on her one night, the sight and sounds of this baby orgy got Josef amorous. He jumped in to join the pups and even extended other delights to them saying their coyote ancestry was very appealing.

Favorite of the litter, Wolf, lets no one touch him except Adi. Wolf could be my second rival. With the war coming to an end, with the Russians circling us, I know Wolf will probably never grow up and that’s some consolation. Wolfie was allowed to play one day up above at the Bunker entrance and was wounded by flying glass. Adi extracted each sliver himself with a tweezers. Afterward, he made everybody put resin on their shoes so we wouldn’t skid and slide on the floor and disturb Wolfie’s naps.

Blondi talks. Or so Adi says. After the Ardennes when he was so depressed, he turned to Blondi more and more. Adi moves her lips, opening and closing them with his fingers and rewarding her with sweet bits of butterkuchen and spinatpudding. She’d growl: “Grrrr… kl… grrrr… kl… ah… grrrrr.” As she now spoke Adi’s mother’s name, Blondi became two loves in one, Klara and Blondi—connected with one tail. Hanging by a thread from that tail is me.

As the war worsens, Adi talks more and more about dogs. Magda encourages this neutral subject especially at meals. Goebbels tells Adi about accidentally stepping on Blondi’s food dish and how she backed him threateningly up against the dripping concrete wall and wouldn’t let him move for ten minutes. Adi said: “You seriously offended her.”

I tried to make friends with Blondi since she was a pup. At the Berghof, I walked her for hours in the mountains while Adi conferenced with his officers. Her doggy rear was often rubbed bare and bleeding, and she insisted on coating her sides with bars of blood as she wagged her tail. Now Adi has her wear a little wooden splint on her tail. A chronic barker from the beginning, she likes to lie on her side and be dragged. My arms still ache from that.

Adi speaks of Odysseus’ dog that waited 20 years for him. He loves loyalty. Odysseus wept when the dog recognized him. One dog story leads to another. In World War I, when he was a corporal, he saw a war dog killed, its back and stomach torn away so that the dog’s still beating heart was exposed. Adi wanted to touch that little beating heart, but it seemed profane. He watched it reverently as it slowly came to a stop like an old pocket watch. Then he buried the heart. The body itself was unimportant.

There were some good times with Blondi, pre-Bunker times. Once the three of us climbed the hills taking a trail through the thick fir forest to come out on a stream-crossing still slippery after rain. We stopped, tasted the water, then Adi gave me a bath like my mother did when I was a child. He moved his hands tenderly over my body, then between my thighs, water cupped in his palms, cool water on my hairy lips that never drink. Adi took a soft leaf to dry me in what he called my hoary marmot, his mustache grazing me. Blondi licked my feet. I startled and suddenly peaked. And Adi rinsed me loose.

Adi and I are mountain people. Die von dem Berg. We love spotting mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and fresh bear tracks. I like to lie down and rest in sword lilies listening to the wild geese while deer and elk stare at us. We’d find a place with no trails where snow can block a path even in June. But September is the best time at the Berghof, especially strolling through the flowery basin where occasional hikers go by in their caps decorated with edelweiss. They are SS hikers as Adi wouldn’t let any unauthorized people in the area. These SS don’t salute. Among intimate German wilderness friends, it’s not necessary.

I loved the deep green grass, and I remember my childhood school nuns telling me that a saint would lean over each and every blade praying, “Grow… grow.” Though it’s an amusing story, Adi hates to hear such things as religion is idiotic to him.

Making me stay off the trails during my monthlies, Adi explains that animals are infuriated by such a scent though he adores my blood. With a “survivor’s bleed,” I can withstand any crisis. Women triumph by bleeding, Adi says. Now, even little Helga will possess this strength.

Yes, that’s what I miss the most, the Berghof. We’d walk holding each other’s baby finger as it was too distracting for Adi to hold hands. Grouse in the trees, an osprey or loon appearing, a golden eagle soaring over… they’re our wilderness pets. As the sun went down, we’d lie on wild roses and bear grass, in the Viennese manner, our legs stretched out in opposite directions, our heads touching—my head against miracles.

Adi would stop and watch the beavers, holding Blondi close to him on a leash, mule deer nibbling close by. It was half a mile to some huckleberry patches where we’d spend an hour berry picking. Adi was enraged when General Krebs told him he had woodpecker soup on this very spot, boiling the pathetic creature in spring water and adding some mountain lilies for flavoring. “There’s no need to kill animals,” Adi says, “no need to fish and hunt when there’s so many berries to pick.”

Adi announces, “This is it. This is the only wilderness we’ll ever have. There will be no more added to the earth.”

We follow closed-off logging roads and scramble up goat trails where lupine bloom with elderberry, fireweed and bluebells. Being strict about sanitary conditions in the wild, we bury our feces and Blondi’s stools at least 400 feet from any waterway and cover the mess with a foot of soil.

Walking in a cow-column along country roads was something he did as a schoolboy working on a farm one summer. Klara cooked for the workers. He and Klara were united in smells of the earth’s wonderful raw odor. In the winter, Klara would help him make snowshoes from thick hickory limbs and rawhide. In the evenings, he would draw and paint as she baked.

He never painted people. Nein. If he looked into their eyes, he’d have to persuade them and that would divert his mind from working. So he sketched bowls, chairs, the simple dross of life. Ebony paint was human enough. He killed color by using black. He learned from being an artist that the first thing you paint you make awkward. Those artists who follow can turn what you did into something more symmetrical because what they are making symmetrical you have already twisted. Daring! That’s what it’s all about. Every decision he makes is daring. Leaders deserve luck only if they accept the hazards of an action. These were the things he’d tell me on our hikes.

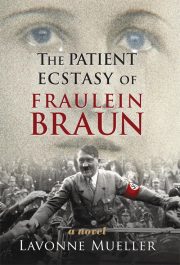

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.