Having confided in me, I felt obligated to respond with equal candor. “I get an allowance from the Führer. But it’s handled by Bormann who makes me beg. He requests I list all my personal purchases. Should I be interrogated for what’s mine?”

“How awful.” The duchess clutched her thin muscular neck protectively, as if begging for money was like getting your throat slashed. “Surely you’ve mentioned this to Adolf.”

“Ja. Ja. He’s been known to rush into his office, open the safe, and stuff bills into my purse. But too often, he’s away. Or in conference. Then I have to account to Bormann for every lipstick. Pads for my monthlies are itemized on legal sheets. Once Bormann gave me some bills that had funny oriental marks stamped on the back. He did it on purpose to embarrass me, giving me money that had once been used in Japan and was now worthless.”

“Get rid of him!”

“Impossible. Most people complain that Bormann never contributed a single idea to our National Socialist World, but Adi likes him.”

“But why?”

“Duchess, he records every detail. And can be called at any hour. One night, at three in the morning, Adi telephoned him to find out the market price of an orange in 1905. Bormann called back with the answer in twenty minutes.”

The duchess reached into her black beaded purse for a small box. “Take it. You won’t have to account for this in front of that evil man.”

I had no idea what she was giving me, but she explained it was a box of perfumed pessaries. Snapping open the lid, she extracted one of the suppositories, lifted her skirt, shoved aside what I thought might be the fleshy pouch, and inserted the sweet smelling cylinder into her vagina. After I inserted one into myself, we walked to the terrace to join Adi and the duke for lunch.

Silently eating his afternoon vegetables, Adi stared at peas so intently they might have been the first peas he’d ever seen. The sun was bright, and Wally complained about the light in her eyes. Adi said: “Duchess, perhaps it’s the glare from the beef on your plate.”

After lunch the duke held a small flat wooden screen in which he did needlepoint, the needle moving rhythmically in and out of the material. “I learned from my nanny,” he announced to us as he stitched some little pugs. “Oh, I have a favor to ask. The duchess and I would like to visit your marvelous marmalade factory in Dresden?”

Finding her brittle and more of a man than her husband, Adi despised talking to Mrs. Simpson. Her lips were little calipers hiding a male tongue. That body was noisy, discreetly passing wind. I attributed her “combustion” to the 161 pieces of baggage that went with her everywhere. Steamer trunks are known to be gassy.

18

ADI NEVER GOT THEM TO THE MARMALADE FACTORY, and Magda said there was a strong rumor that the duchess was to divorce the duke and marry the Pope.

Perhaps if the duchess had brought all her dogs to Berchtesgaden, it would have been difficult for Adi to detest her.

There was a time Adi considered kidnapping the duke and restoring him to the throne in order to get rid of Churchill. But it was the duke’s wife that put an end to that plan. Wally was considered more of a nuisance than Winny.

After they departed, we learned Wallis told their hall-boy that the Berghof was lacking the simple basics of civility.

I hate to think what the duchess would think of the Führerbunker.

Following the progress of the enemy as his adjutants phone it in, Adi moves pins of battalions that are no longer in full strength on white greaseproof maps. He makes inroads with tanks, his magnifying glass and spectacles resting on truck convoys that are greatly depleted. Sometimes I think his maps are more appealing, even more sensuous than me. He fondles them, runs his hand along their spines, caresses each juncture, leans into towns and cities and beckoning country roads as if he were penetrating their forked curves and splayed mounds.

But maps aren’t my rival nor is Magda who loves him madly though I don’t believe she ever got physically close to him. With Adi, one never knows to what extent he lets himself get intimate. Sometimes he considers a cheerful hug as virtually fornication.

To have all of him concentrated on just me would be heaven. For when he touches me, he’s inwardly dealing with some logistical problem. When his eyes are focused directly on me, his hands are fidgeting with orders and code sheets. His heart beats so secretly when we embrace, I can’t feel the slightest pulse.

Thinking about his doubles, I fantasize they could fill this ache. But they’re merely substitutes for the real thing. Would they be better than nothing, the long nothing hours when he’s working and traveling?

Adi has four doubles. I can tell instantly they’re not Adi. In cars or planes or balconies, at a distance, the average person wouldn’t know. Sepp, Ewald, Jochen, Baldur. They’re Adi’s height with his same facial structure and a little mustache. They’re indeed handsome as my Adi is handsome. As close as they are to the original, they lack that fiery beauty of the real thing. Adi is not friends with these men. They’re only mannequins or what he calls “gestures of immolation.”

A driver tried to shoot Adi in the arm. The pilot Kummer wanted to take him up in a plane so he could push the Führer out. An idiotic potato farmer threw a hatchet at Adi’s Mercedes. Then there was the Munich banker who couldn’t shoot straight. Finally the awful bomb under his desk that didn’t kill him but caused his ears to ring, his arm to shake and persistent agony.

“Adi, let Dr. Morell give you something for your pain.”

“Pain is good.”

“How can you say that?”

“Don’t leprous people pray for pain?”

“You’re not a leper.”

“Some of my generals think I am.”

Then I tell Adi his arm would get better if he exercised it, but he only says: “Not until I get the injury out of my mind.” Adi can’t be destroyed. Never. Unless He himself chooses it.

When a young girl jumped up and kissed him, he nearly fainted as he felt her sharp wire metal glasses on his cheek and thought it was a knife. Later, he became apprehensive when people threw flowers at him fearing hidden grenades.

It was Magda who knew the four doubles, not me. At least on one occasion. I felt no jealousy as they were hardly the real thing, and if they helped her release that passion she has for Adi, then why not? Her longing for Adi is annoying. I understand how one must feel to want him, to yearn, knowing the impossibility of it. One day, holding a bag of fresh cherries that were bleeding through the paper bag, she confessed, “I have an appointment with the Führer’s four doubles at the Hotel Klomser.” Smiling in acceptance and maybe with a hint of superiority, I knew she had to settle for second best.

“They’re all coming at once. Arriving together at the Potsdamer station.” Magda had chosen one of her more conservative print dresses with a pink bow at the modest neckline. Being with four Hitler doubles demanded decorum. However, when the pink bow was removed—and it was arranged to be removed easily—there was ample cleavage ready for exposure. Magda creamed the sides of her breasts so that in the manner of a ski lift, one’s hand could glide easily to the summit house.

“Will it cause riots?” I wanted to know. “Four Führer doubles stepping off the train?”

“They’re in disguise,” Magda explained.

“Have they reverted back to the people they really are?”

“Nein. How ridiculous. What would be the sense of going backwards?” Magda is always annoyed at my Bavarian practicality.

“Who are they pretending to be when they get off the train? I asked.

“Announcers for Radio-Abwehr. With their hair and mustaches dyed red.”

“All four of them?”

“Each with a different shade. Two are wearing lifts in their shoes, two are wearing no shoes at all—just slippers to appear short. All this for me.” Magda lightly touched the bow at her neckline. I could tell she was anxious to be rid of it. “They will convert back to Führer doubles the moment we enter our hotel room.”

“Does the Führer know you’re entertaining his doubles?”

“He’s happy to have them rewarded with the company of a good German woman. But he reminded me they’re still on duty. I must be aware of that at all times. At any moment one could… could…” Her frown and sputtering words made clear that losing one of the four Führers at a particular summit moment would be devastating.

“Where were they when that awful farmer tossed a hatchet at our Führer?”

“They were not sent for at that time and are very remorseful about not being there.”

“Especially since the Führer survived, as a double would have,” I said. “And the cherries?”

“For them, the dear ones. Fresh fruit from my summer home.” Cherry juice stained her fingers making delicate ruby swirls.

Magda did meet Sepp, Ewald, Jochen, and Baldur at the Potsdamer Station. The train was on time. They went directly to the Hotel Klomser where to her horror Magda found all four men impotent.

They lined up before her in bed. Four naked bodies with their poor putsches hanging down like old soggy fruit. It was so distressing that at first Magda felt they should be dismissed from their honor. Gradually she realized that perhaps they were more valuable this way—without distractions. Not that they cared for men, either. They just didn’t seem to care for anything but being a Führer double.

She and the four men sat on the hotel bed and ate cherries, the pink bow at her neck never disturbed. She felt unduly deprived having prepared herself with no underwear. There’s something sad about a woman with no underwear reduced to eating cherries.

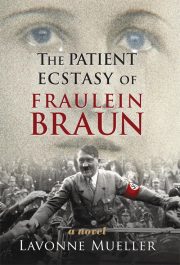

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.