Herr Doktor Goebbels waved a carpenter’s apron like a flag with his own hands in all the glory of the people. Those wonderful days when the German workers knew who loved them. He once backed a Communist up against the wall and gave him a bloody nose. He’d done it all for Germany and asked for nothing but poetry in return as he is “Kunstmensch”—a man of art. All those glorious meals at the Horcher restaurant where the Führer had talked to him of Linz. All those stirring chats about Napoleon who admired the silk weavers of Lyon, who built porcelain workshops, encouraged furniture designers, protected historical buildings. How was it possible that a Frenchman so full of pain and so squat and peculiar looking could be so marvelous? The Herr Doktor stops talking abruptly and stares at me. “Napoleon said he wanted to marry a womb. The Führer and I understand that’s the only way for a soldier. Yes, we know what it takes. Our Führer used to carry Schopenhauer in his greatcoat pocket all through the First War. Now he carries Nietzsche.”

Magda nearly divorced Josef embarrassed by the mistresses her husband flaunted on Baldur, his white motor yacht where he poured cheap wine into carefully dusted bottles of Chateau d’Yquem 1910 and gave the women perfume stockpiled from occupied Paris with strange names like Je Reviens. Magda got so angry she couldn’t endure Josef’s presence in the same café. So they divided Berlin’s restaurants between them. Adi put a stop to that and gave Josef a strong lecture on his obligations to the Reich. Off limits were the actresses Jenny Jugo, Luise Ullrich and Lida Baarová. Josef Goebbels had to meekly ask Madga’s forgiveness. Then he gave the Führer a gift of 18 Mickey Mouse films along with Der Schneemann, the cartoon Snowman by Hans Fischerkoesen, as they share a great love of cinematic art. In return, Adi gave Josef an armored Mercedes with bulletproof windows, especially pleased after Goebbels led Brownshirts to see the movie All Quiet on the Western Front and released white mice in the aisles. People ran out of the theatre screaming, and the film was suppressed.

“Where did you get the white mice?” I asked.

“Shipped direct from the old Knickerbocker Hotel off Times Square in New York.”

“Be serious.”

“Ratten hinaus! Donated by the science labs at Dachau where rats are kept.”

“Why Dachau?”

Goebbels has a policy of ignoring questions he doesn’t wish to answer. “I’ve always been careful with film. Enemies can easily hide there. I wrote to six American movie companies with offices in Berlin ordering an immediate dismissal of all Jews working for them—to stamp out that Friedrichstrasse crowd. I consider myself an advocate for natural culture.”

“Did you demand Proof of Descent from every film actress? Even the ones of a more personal interest?”

Again he ignores my question. “It’s always so pleasant to be with you, Eva.”

“I never congratulated you for getting an honorary doctorate from the University of Breslau.”

“I get many honorary doctorates, my dear.”

“Is that why you insist on people calling you Herr Doktor?”

“Doktor G will do, though pretty girls can continue with Josef, of course.” His look is outright jaunty.

“You know what some of your men call you?”

“Gobbespierre. After Robespierre.” He smiles. “Though I’d never admit it, I find that dashing.”

“They say you spend your time with literary chauffeurs.”

“Who is they?”

“Bormann.”

“What do you expect from an illiterate?” He suddenly looks down at his feet. “Eva, tell me honestly. Have you secretly despised me?” Running his fingers through his thin hair, he touches my arm to show that he now wishes to be more personal.

“Never,” I lie.

“Even a little? For not serving in World War I? For this tedious lament I carry around for the humble Russian soul? The very country that wants to eat us up. Do you hate me for being a cripple?”

“I never think of that.” But I do.

“I like a little bitterness with everything. I’ve been with women in Africa who have tattooed breasts. Some with two toes. Split feet are admired in many tribes.”

“How do you know that?”

“I’m the propaganda minister, am I not?”

I know that if Adi has only one man left, Josef will be the one.

“Let me show you.” Before I can demure, he unlaces his shoe, and I see the soft, pink deformed foot so sly and shifty it makes me think of that wobbly soft bunch inside his underwear. “Do you find it ugly?” he asks. He sees that I hesitate. “At what point do we declare something beautiful? Was all that scratching on cave walls deliberately made to be beautiful? You may prefer the normal or the regular, Evie, but Kant tells us that we instinctively look for form in whatever we behold. Even this. My foot is an aesthetic lesson.”

In between her lovers, Magda uses this “aesthetic” appendage often, claiming his deformity as a tool to pry her wider. That opening which issued six babies into the world hardly needs to be stretched.

Adi, who informs me repeatedly about the best and brightest future race, won’t acknowledge Goebbels’ deformed stem. “Look in any alley,” Adi says talking about everyday people who limp and lope through life, “good common Germans.” But must Goebbels be short as well? Is that why the Herr Doktor likes Russian literature so much? He can hide in the wide tall sweep of Russian characters.

“I was once temporarily impotent,” Goebbels confesses. “I went to a Buddhist temple and was told to have my penis bitten by a wasp. An old Buddhist custom. It did take care of the matter.”

“Was it painful?“

“On the contrary, though it did burst a blood vessel. But that’s all over with. Even my tapeworm is gone. Do you remember the party at the Sans Souci Hotel when I gave the Führer all those Donald Duck films?”

“But Josef, you told me yourself that silly Mr. Disney erased all the udders from cows in his cartoons.”

“He was quite right to do so. We must think of our children.”

“I would rather see films with real people. Real people don’t turn on their axis. Real people aren’t jumping mushrooms, spiderwood faces, purple cornflower horses, leaves with bloodless veins.”

“I adore fantasy, Eva. After all, I live in the country of the Brothers Grimm. I prefer the natural literature of the people, the Volkspoesie like the Grimms’ Kinder und Hausmärchen for the children. But remember, all those people in the Grimms’ tales acquired methods of thievery.”

“Only against monsters and witches.”

“Ah, then you do know the Grimms.”

“Adi loves fantasy and cartoons. So I have to be familiar with them. But those things are why he hates to dance, and I’m forced to waltz with doorknobs.”

“Das Lech is why he hates to dance, my dear.”

“I’d hold him so tightly not a drop of his essence would dare leak away.”

“Dancers are considered traitors.”

“Not unless they jitterbug.”

“Dance—and one forgets the war, Eva.”

“I would think it’s helpful to forget the war from time to time.”

“If it’s so helpful, waltz with me. Here. Now.” He gives off a forced Bohemian flair.

“There’s no music.”

“There’s imposed realism.” Goebbels takes my hand and begins to sing softly, “Es wird ein Wunder Geschehen.” It’s the popular inspirational song being sung these days… “A miracle will happen.”

“When will it happen?” I chant back.

“Miracles take time.”

17

SINCE ADI HATES TO DANCE, I see no reason to refuse Josef. We float around his office desk that is really a butcher-block table from the burnt out Rheingold Restaurant that once held dissected chickens and slippery ducks coated in oil. Now instead of hens, it holds cluttered requisitions for supplies that are nowhere to be found. I’m lighter on my feet than Magda, and he can move closer to me as my breasts are small, firm and resilient. He does lean against my orbs that become soft claws. Feeling a sense of modest revenge, I think of Magda and her little double, Helga, and beg him to tell me about his mistresses, all those actresses. He gave them up for a short while at the Führer’s insistence. But he couldn’t stay away from them, and Adi had to announce that a wife should not be annoyed over anyone as silly as an actress. If I were one, Goebbels might forget himself. But I’m Eva Braun.

“My actresses cry out in passion with a chaotic welter of so many voices and with such projection,” he brags. “Each has her own special nostrum.”

Josef wants to kiss me. It’s quite all right, we’re comrades, are we not? We love the same man. What is a simple moment in the eternal? He takes nothing from the Führer who never kisses.

Adi won’t kiss me on the mouth as he’s kissed no one on the mouth except his mother because the tongue can have a yellow coating indicating bacteria or cracks across the width revealing loss of nutrients—teeth marks along the edges mean bad digestion. My Adi can’t know what’s under the tongue, wet and hiding. As a boy, he saw a prostitute in Linz stooped in the shadows and shining a flashlight on her legs. Leering at him, she tried to get the few coins in his pocket that he thoughtlessly rattled as he walked. The prostitute then shined the light on her mouth and lifted her chunky tongue and he saw parasites there—tiny swarming parasites nesting in a cove of glistening pink. Two entire chapters of Mein Kampf are devoted to the evils of such women.

Josef says I’m silly to think he’d desire anything but the mouth beneath my nose. He simply wants me to kiss back and is patient. He uses his two bony fingers to purse my lips, then gives me a quick peck.

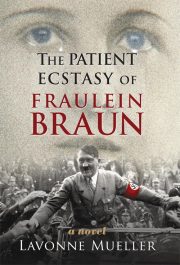

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.