Adi’s spirits go up and down so rapidly these days that I try to think of something other than battlefields. War hinders pleasant thoughts. Yet Adi is near me, and that’s what is important. I’m mistress of this Bunker and have furnished our home and done little things for him that would be impossible to do if we weren’t hunkered down below. Simple things that one might find silly. Like taking shells apart to decorate picture frames. Sometimes I imagine I smell new lumber and fresh varnish the way a bride might smell in her new house in another time. I look at white concrete and try to see golden pine and cushioned window seats of creamy velvet. That’s idle dreaming like those elegant patisserie shops I long for on Kurfürstendam or the Schlosscafe with plenty of schnapps and jolly waitresses. When will I ever see my Adi at the Berghof in his short leather pants and Bavarian hat with its saucy little feather? With the sound of stags rutting, we would amble with Blondi, Negus, and Stasi, pausing by the marsh marigolds, the daisies, and the pink sweet peas as trees exposed their crotches to us wantonly. Grasshoppers would snap their wings like a Nazi salute as we walked by. The dogs tried to catch the play of sunlight on the leaves of mountain maples, Stasi leaping like a greyhound. I’d pick purple asters and pin them in my hair while Adi told me Mozart was influenced by birdsongs. And in the winter months, Adi would kneel before “frost flowers” marveling in their petals of flat ice crystals. What happened to those times?

After several hours, Magda and I sneak into my room and peer through the half opened connecting door to see Adi and Helga on his bed. She calls him the “pigtail king” for only he can put five perfect pigtails in her hair. Removing her hairnet, he carefully parts the golden mop of curls into five sections and twists them into little braids. As she nuzzles her head in his lap, he tells her the story about finding an orphan puppy that he had to feed with a little tube of milk. She leaps up and sucks on Adi’s ear wanting to be fed like the doggy. After she slurps loudly for a full ten minutes, Adi mumbles Brahms’ “Lullaby”:

Guten Abend, gute Nacht,

Mit Roslein bedacht,

Mit Näglein besteckt.

Schlupf’ unter die Deck.

Adi leaves for the map room steering a sated Helga to her bedroom. As she goes happily to her cot, Magda follows and I’m left alone in the dining room thinking: Was I ever like Helga? Could I have ever been so awkward and childish? So skinny and silly?

I imagine myself as a little girl burying my face in Adi’s waist, my hands innocently around his thighs. My fingers find his pleasure, and I make him happy not even knowing it.

But who wants to be a child? It will soon be my wedding night. But I worry… is Hans right? Should we stage a breakout? Perhaps after we’re man and wife? But Adi tells me he has other plans.

Wearing riding breeches and carrying a whip under his arm, Josef Goebbels comes from the map room walking erect in his leather jacket with silver armbands that now look like the color of concrete. His face is bloated red with rage so that the pox scars on his cheeks are clearly visible. He has high blood pressure and when agitated, which is mostly every day, he becomes scarlet down to his scrawny neck. As the doctor has no patience with so ordinary an affliction, Dr. Morell injects him with a sterling silver syringe for everything but blood pressure.

It’s obviously not going well in the map room. It never goes well these days.

“Is he shouting?” I ask.

“That a man like the Führer has to shout after suffering the horrors of Dresden. Think of it, bombing a city that’s a showcase of historic treasures. Is that what Churchill calls civilization? Our children are singing,

“Mein vater ist in Krieg

My mother is in Dresden

Dresden ist abgebrannt

Dresden is burnt down.”

He rubs his sweaty forehead and then scratches his tense neck. He tells me his voice is strained as he just gulped undiluted adrenalin for energy.

I think of the Dresden vase in my bedroom at the Berghof falling and breaking into pieces, and the Rilke line Goebbels often quotes: “Be a ringing glass that shatters as it rings.”

“Why are you smiling?” he asks.

“We Germans will ring as we shatter.”

“You remembered Rilke.”

“You’re the one who gave me my Rilke lessons.”

“Poets will remember our Führer. But will the common worker also realize how great he is?” Goebbels asks.

“Most German houses still have Führer niches in their bedrooms, little Führer-altars with paper roses and his portrait. Though badly damaged, the Wertheim Department Store sells glass frame photos of Hitler.”

“Ach ja! As they should,” he tells me.

“Remember how Magda always played gramophone records of the Führer’s monologues after dinner? At the Berghof?”

“Now those gramophone records lie smashed at our bombed Brown House in Munich,” he tells me. “Oh, Eva, there was a time I only worried about rectal bleeding. There was a time I thought only of making strong ties to England so that we could intimidate France.”

“How glorious when we put all our occupied countries on Berlin time. I’d sit on the grass at the Berghof thinking, ‘Paris is exactly now.’”

“Yes, my dear girl, the glorious days of the Berghof. Sometimes the Führer would talk to the village people… coming out the side door on an afternoon in his gray, chalk-striped suit… smiling, shaking hands… accepting flowers.”

The Berghof. Dürer’s The Violet in a simple silver frame on the wall. The plain Landhaus country style furniture Adi loves. Sitting on the terrace, the smell of wild morning glories, the sound of shuffling cards. Playing Ping-Pong as we sang Beethoven’s “Ode To Joy,” drinking, laughing, a canary in the cage, the wind a gentle comb to our hair. Mountain knapweed, thimbleberry shrubs, lanterns hanging in the trees. Paths scattered with moon spots and balsam fir. Nature bursting into color like a violent fire. I fought all the wrens for the best blueberries. Ilse Hess would take off her ruby rings one by one (each the size of a parrot’s perch) before playing Bach’s “D-Minor toccata” on the baby grand piano for the Reichstag deputies. Leaving the gold leaf dinner table, Adi would throw a flower to one of the ladies.

“We occupied Athens as the frightened women washed their icons in wine. Their prime minister committed suicide,” I announce proudly.

“Now they’re singing and tearing up occupation money in Athens, and I’m establishing a Werewolf Guerrilla Resistance. But let’s drink to good memories.”

There’s the smell of bland spit and damp leather in Goebbels’ office. He shoves aside papers he tells me were taken from American dispatch riders, papers that will never be evaluated. A bar of Lux soap is on top of a file cabinet stuffed with interviews of Germans repatriated from America. Pouring two drinks in glasses rimmed with specks of faded gold, he says the Americans are occupying Aachen where his mother is buried. He remembers the letter of condolence from Adi when she died, the most sensitive letter ever written about the death of a mother—telling him soon his agony would dissolve into the glorious despair of remembering.

Now… Josef’s hometown, Rheydt, with his dear childhood house on Dahlener Strasse, was handed over to the Americans without a fight.

The concrete seems to sweat more in this room, rivulets clinging and streaking the walls as if even concrete knows where the most important people gather. Goebbels takes a full gulp emptying his glass and pouring another. He talks about the old days, how he marched with workmen, side by side, holding up shining shovels that his adjutant polished like the brass buttons on his jacket, marching brother to brother. Oh, how he loved mingling with the masses, he, who came from their social class but was now a man of letters—a doctor from the University of Würzburg, his diploma with rite superato—singing with people who didn’t know the Mann brothers from any man. Then the Führer passed the Enabling Act dispensing with parliamentary government and in a single stroke brought the workers to prominence. But the trade unions ruined that. Unions getting money from Russia became enemies of the Reich. Moscow gold invaded us. Then we got saddled with too many stupid war generals… such as Rommel, who was like some old medieval manuscript full of errors, superstitions and silly customs. Montaigne’s words are a prediction from the past: “One ought to fear the generals more than the enemy.”

Tears are in Goebbels’ eyes as he tells me how he visited the grave of Adi’s mother two years ago. He arrived in Leonding not far from Linz and stood in that solemn village cemetery where the Führer’s mother rests for eternity. He was overcome with wonder at the humble tombstone that covered the mother of such a genius and recited John Donne’s poem before her grave:

“Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful

For thou art not so.”

Since then, he keeps a picture of her grave on his desk remembering her cancer and the words of Tolstoy that a woman who has never been ill is a monster. And that’s why he dislikes that American artist Whistler whose famous painting of his mother has the folds of her gown looking very sinister.

After visiting Klara’s grave, he went to the Führer’s boyhood home, picked leaves off the maple trees in the yard as the little Adolf might have done as a child, to make a bouquet to place before the house. Then he stood there inhaling the air of Linz before eating a haunch of wild boar at the Weinzinger Hotel.

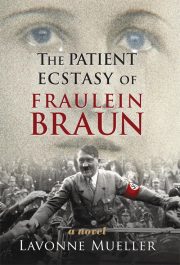

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.