“I have five Fieseler-Storch airplanes,” Hans announces.

“Are those the ones with open cockpits? Josef would never approve. Not for the children.” Magda pulls the baby close to her breast.

“There’s room for two children on your lap. Me in front. Two on Fräulein Braun’s lap in another plane. Two with my aide Colonel Beetz in another. Three planes for the Führer, his clothing, paintings…”

“The Führer has given orders that high ranking personnel are only to fly in aircraft with at least three engines.” Hair frizzy from the Bunker dampness frames Magda’s face. Frizzy hair makes her cheeks look puffed. I notice thin little squint lines by her eyes.

“But my planes can take off and land in meadows, if need be.”

“How safe can that be?” Magda moves so that her large crotch no longer shows. Hans is bereft.

“My full concern is for Mein Führer, you, the children, Fräulein Braun…”

“My husband?” Her lips turn down in that taunting way she uses to be coy.

“Herr Bormann, too.”

“Herr Bormann?” Magda chuckles. “He can carry the Führer’s Iron Cross on his lap.”

“Talk to her,” Hans says to me in a desperate tone. The crotch that just disappeared could possibly disappear forever. He holds a list of all the Bunker people who will fly to the Berghof as soon as the Führer orders a breakout.

“The children will be quite safe here,” I answer, almost believing it.

“We’re surrounded. If the Ivans find such women as yourselves…”

“What will they do to me?” Magda teases.

Hans looks at her tenderly, his lust momentarily forgotten. “They will instruct beauty.”

“You’re such a silly poet. And just when I wanted something more… graphic.”

“At the Weisser Krug Inn, women were raped by the Russians and nailed through their breasts to the walls. At the Roter Krug Inn in Gumbinnen, the same thing. Frau Goebbels, I’ve ordered a barge near your island estate. With plenty of food. Go there and hide. I’ll come and fly you out to Switzerland.”

Helmut jumps up and down in a pair of German boots that have springs in the soles for leaping over trenches. Two children are naked and jumping in water wiggles seeping from the scabby walls. They begin to fight. Separating them, Hans bounces Heidi on his back galloping to Magda’s side.

“Do this horse a favor,” he pleads. “Let me fly you out.”

Magda pats his pony head. “You can trot the children to their room. It’s bath time.”

“All of you, on my back,” he calls. Giggling children squeeze on Der Chef Pilot’s back, one on his neck and little Helmut bouncing and holding the end of his uniform like a tail. Sitting in a corner staring in disgust is Helga.

As I help unbutton the children’s clothes, Hans carries water to a tub.

Helga sits on a chair with her legs tightly crossed.

“Is the half-wit pilot going to live here?” Helga asks.

“Of course not,” I say.

“Of course not,” Hans repeats, saluting the children playfully. “I have wounded to fly out of Berlin.”

“What kind of wounded,” Helga asks.

“Men who have fought bravely for their country.”

“What kind of wounds?”

“No need for that,” Magda says, straddling the baby on her ample hip.

“I want to know,” Helga says.

“No, dear. It’s unnecessary.” Magda puts the baby on a cot. The children have little cots just like soldiers.

“I have a right to know. I’m a woman now.”

“That you are,” Magda agrees proudly.

“Tell me, then!”

“What is it you wish to know, dear?”

“Do brains pop out when soldiers get shot?“

Magda signals for Hans to answer.

“Jawohl.”

“How far?”

“If a man is shot in the head…” Hans begins looking nervously at Magda.

“How do people look when they’re bombed,” Helga interrupts.

“They get roasted purple and shrink to half their size.” Hans is seized with an honesty sanctioned by truth. He hopes this morbid account will help his demands for a breakout.

“And little kids? Like my brother and sisters? How do they look when they’re bombed?”

“I saw a direct hit on a school, and the children were fried in water pouring from a blasted boiler.”

“Fried like sausages?“

“Often, that’s so.” Der Chef Pilot looks hesitantly at Magda, but she’s only smiling in complete acceptance.

“But the brains remain gooey?” Helga asks.

“How do you mean?”

“Like pudding. And don’t try to make things better.” Staring boldly, Helga only allows herself to blink in careful determination.

“Yes. It’s pudding,” Magda says in a patronizing voice. “But what else, dear, would you expect brains to be? Made of granite? Then how could you hold up your lovely head?”

“Or toss your pretty little curls back and forth,” Hans adds.

“That reminds me, I must fix your hair. It’s really out of control.” Magda moves towards her daughter.

“Only Uncle Führer knows how to fix my hair.”

“May your mother help, the mother who loves you so much?”

“A mother who is beautiful as well,” Hans adds.

“You’re both treating me like a baby. When does Uncle Führer get finished with his meeting?”

“You know he’s never really finished, Helga.” I place my arm on her thin shoulder.

“Can’t I help you, dear? Just this once?” asks Magda.

“Uncle Führer is the only one with any sense around here.”

“Is that the way to speak to your mother?” Hans asks.

“Stay out of this, please, Herr Baur.” Removing my arm from Helga’s shoulder, Magda brings the girl closer to her side.

“I don’t want to be babied, mother.” Helga pushes away and sits defiantly on her cot.

“Your mutter is only trying to assist you,” Hans offers.

“Der Chef Pilot should concern himself with propellers—not little girls.” Magda sits on the cot protectively next to her daughter.

“I’m not a little girl,” Helga shouts, jumping up. The children stop playing with a wooden car on the floor and gawk curiously at their sister.

“We know you’re not a little girl,” I say remembering how she took in everything at the shelter orgy.

“What do you know? You don’t even have any kids,” Helga shouts.

“Is that the way to speak to Fräulein Braun?” Hans asks.

“Der Chef Pilot should not be telling my daughter how and how not to speak.”

“I’m only attempting to help,” Hans offers. His tight lantern face lifts upward in authority.

“Help? You can’t even get my stupid mother on your silly airplane because my baby sister won’t eat her in your dumb contraption,” Helga says.

“Breast feeding is not eating your mother,” I correct.

“This little brat needs a spanking.” Hans is now angry.

“Don’t any of you touch me,” Helga screams. “Lay a hand on me, I’ll tell Uncle Führer.”

Suddenly, Adi is standing in the doorway. “What’s going on here?” he asks sternly.

“They’re a bunch of idiots.” Helga runs to Adi’s open arms.

“There, there,” Adi says, stroking her head and looking at the other children. He’s happy seeing his Nazikinder, his wonderful blond Nazi children.

“Morons. All of them.” Helga whines, her face buried in his tunic.

“There, there,” Adi whispers, looking at us with a knowing smile. “Perhaps you would like to take a little rest in Uncle Führer’s room, my schönheit. My beauty.”

“Can I?”

“Only during my situation briefing with General Krebs.”

“That old stink-pot!”

“Helga! Don’t talk like that in front of the Führer.” Magda is finally upset.

“She’s quite right. He’s a stink-pot,” says Adi.

“See. I told you so.”

“Still, you must wait until I finish with him,” Adi says.

“Will you come in and fix my hair? Like you always do?”

“Der Führer is much too busy for that,” I say.

“There are a few minutes here and there,” Adi offers. His patience and loving pats make me envious.

Holding Helga’s hand, Adi leaves. The hair net she wears to be grown up is tight and mashes down her golden curls so she appears bald. The little bald lady looks back at us smirking. Magda cherishes those smirks, her glory transparent as her daughter goes to the Führer’s room to lie on his bed and wait for him.

“Now there’s your answer,” Magda tells Der Chef Pilot. She picks up a popular children’s book titled Mama, Tell Me about Hitler to read to the children.

Hans looks sadly after his Führer who left without addressing the breakout. Saying nothing, he leaves the room for the iron staircase. I watch him slowly spiral to the top.

After Adi settles Helga in his bed, he’ll go to the bathroom and swab his buttocks with antiseptic lotion because he leaned against the map table. Who knows what his generals bring in from the war?

It’s disturbing to the Führer to think in terms of negotiating a truce. Hess’ maneuver in May of 1941, flying off to try and make peace, is a stupid act that has nothing to show for itself but the wreckage of a perfectly good Messerschmitt and his imprisonment. His wife influenced him, trying to make Hess a hero with his flying stunts and war record. She did it hoping he’d get special treatment after the war from the Allies.

Maybe Hans’ plan for a breakout from the Bunker is another crazy Hess idea.

The Russians are close and fighting on top is fierce. As a Catholic schoolgirl I was taught that St. Thomas Aquinas pronounced war perfectly acceptable when waged for the right reason. He seems the only smart saint. His wisdom soothes me though Adi hates religion and its false concepts.

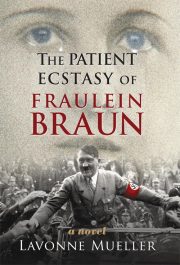

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.