“Die Fahne hoch

Die Reihen fest geschlossen!

The flags held high,

The ranks stand firm together.”

The children chant, “The flags held high, the flags held high,” as they raise their chubby arms.

Wiping condensation from the metal doorknob with his handkerchief soaked in vinegar, straining to look calm, Adi leaves the map room. Veins on his forehead and temple bulge. His generals are behind him. General Krosigk, a whip hanging from his waist that drags on the floor and tangles between his legs, talks about a new plan for resistance in the lake region of Strausberg as he climbs the spiral iron staircase.

“My generals have undone me,” Adi says growling as he watches them go up the stairs. He gives a forced smile. “Like those silly obese generals in Napoleon’s army who were too fat to ride horses and led the troops in carriages. I should listen to Machiavelli: Guard against generals, do away with them, eliminate their esteem.”

Adi’s generals are skeptical of his military strategy. Generals, he reasons, are ungrateful, their minds on glittering guns, tanks, planes, bombs. They never listen to him. As for their quirks—when things go wrong, he hears from them but never when they get themselves and their troops slaughtered. It’s ridiculous for him to stand in front of such fools. You don’t have a bunch of kids in knee pants telling an experienced teacher like himself how to conduct class. Generals get too much praise that belongs to the trench soldier. Nevertheless, Adi ends his meetings with them asking sensitively about their wives and children and giving their families boxes of chocolates knowing that it’s prudent and off-setting to reward your enemies before your friends. That’s an important part of being the Führer.

He takes a few silent minutes to hate all of his generals, signaled by a series of tiny jerks inside his trouser legs.

Seeing the children, Adi smiles broadly and picks up a ball slick from Bunker dampness. He bounces the ball and sings softly to them: “Die Fahne hoch! Die Reihen fest geschlossen!… close ranks up tight…” Then he takes out his comb, puts a slip of paper on it and hums, the children humming with him.

As Helga puts her arms around Uncle Führer’s waist, he pats her hair. Taking a sugar cube from his pocket, he lifts Helga’s face, fondles her mouth, parts her lips lovingly to place a sugar cube on her tongue. Is he thinking of Geli?

“Sugar! Sugar! We want sugar,” chant the children, forgetting their humming, their waving fingers frantically clawing at Uncle Führer’s bulging pocket. As he hands out sugar cubes, he also gives one to Magda, Hans, and me. Loudly sucking, Hans speaks about a breakout as he rubs his Gold Wounded Badge (which he was awarded after five injuries) and flexes his chest so that his other medals jingle softly. He reminds me of a skilled piano player who never comes to the end of his keys, who leaves a vague hint of the final note.

“No talk of that in front of the children,” Adi says softly.

Magda hands the crying Heidi to Adi who cuddles the child gently saying: “Engelchen. Little angel. How well you cry.”

“Oh, my, oh, my,” says Hans to the children. “I’ve eaten the wrong end of my sugar cube first. To digest it, I have to get upside down.” He stands on his head and lets his legs slap loudly against the damp wall.

The children scream excitedly. Even Helga leaves Uncle Führer’s side to examine the rush of blood that turns Han’s face bright red. Adi moves the baby’s head to see Hans. Sitting on the floor, Magda smiles in glory as we adore and entertain her children. She uses them for her own vanity.

Adi used to play hopscotch with the children. One of his secretaries who visited New York taught him the game. When he found out hopscotch was once a religious game in which the final square is heaven, Adi forbade the children to ever play it again.

Once Adi was driven to a toy shop followed by scout cars and riflemen on motorcycles. He bought baby booties for Magda’s approaching delivery. Placing one bootie on each of his thumbs, he cooed to them much to the astonishment of the clerk. The next year he bought the children a rocking horse and when the tail was broken, he made one from his belt.

Adi leans down to little Helmut who has a constant running nose. “Now do you know what month it is?”

“April, Uncle Führer.”

“And what comes after April, Helmut?”

“May.”

“Very good. And what comes after May?”

“September, Uncle Führer.”

“Excellent. You’re a bright boy.” Adi straightens, then looks down with pleasure at Helmut’s curly blond hair.

“But Uncle Führer,” Helga says indignantly, “September does not come after May.”

“Helga, sometimes it does.”

Fräulein Manzialy trots in from the kitchen to ask her Führer if he wants the surprise now.

“Surprise! surprise!” the children scream. Falling gracefully to the floor, Hans is forgotten.

“Ja,” Adi says, handing the baby back to Magda. “Bring the surprise.”

As Adi goes to his bedroom, the children follow. But he closes his door on them, and they stand outside pounding and calling, “Uncle Führer. Uncle Führer.” After a few minutes, he opens the door dressed in lederhosen for he wants to be a common man especially with the little ones. Did not the Kaiser wear a gray uniform like an ordinary soldier?

Fräulein Manzialy rattles a saucepan for a dinner bell, then enters with a large glass of buttermilk for Adi, plum juice for the children, warm bread and a tray of corn on the cob, buttered and slippery.

“Corn on the cob. It’s wild food. The Red Skin natives of Canada eat it,” Adi tells us while adding three spoons of sugar to his buttermilk.

“But so do the Americans.” Magda is reluctant to touch a cob.

“Americans only eat from tin cans,” Helga corrects.

Adi forms a caricatured smile.

“It’s American Indians who eat it,” I add.

“We would do well to study such Indian skills of warfare.” Hans eats a slice of bread as he carefully eyes the corn. “I’ve researched how Americans killed their Indian inferiors. And how their plantation owners ghettoized black people.”

“American plantation owners? I’ve heard they were stupid,” Magda says.

“Plantation owners in antebellum South were known to conjugate Latin verbs.” Adi’s head is down isolating his face. A gentle man who wouldn’t even harm a dish, he moves his palm like a caress over the bowl and anyone seeing such a sweet gesture could not help but love corn.

“Latin has to be better than their awful American slang.” Looking intently at her corncob, Magda smiles.

“I hear their great hero, Frank Sinatra, didn’t weigh enough to make the draft, Mein Führer,” Hans offers.

“We have little to learn from Americans themselves.” Taking a napkin with faded beet marmalade stains, Adi puts it carefully by his plate. “The English are another matter. Their industrial leaders through the years have developed a superior base. And I am sorry that I have not managed to bring the English and German people together… though we started out with promise.”

“Didn’t Lloyd George give you a signed photograph of himself?” Hans asks.

“It read: ‘To Chancellor Hitler, in admiration of his courage, his determination and his leadership,’” I recite proudly.

Adi looks at me pleased.

Not to be outdone, Magda chirps: “Henry Ford admired you as well, Mein Führer.”

“Because I’ve always known that America’s outstanding achievement is technology.”

“Of course Ford was smart enough to be an anti-Semite,” Hans adds.

“Didn’t you once wish to make an alliance with America’s Ku Klux Klan?” Magda asks.

“The Klan was not political enough,” I tell her.

Helmut is making little soft balls of bread and using the crust to build a fort, his running nose snorting. The other children are restless and sip at their juice making loud smacking sounds. Helga looks at the Führer with adoration.

“I have no respect for U.S. troops. They like all the comforts of home at war. They’ve dishonored the influence of Baron von Steuben who was George Washington’s drillmaster. West Point used to have the spirit of von Steuben.” Adi finishes his buttermilk in one long gulp.

“I’m mostly interested in America’s Civil War, especially the details of Stonewall Jackson’s maneuvers in the Shenandoah Valley,” Hans says.

“Yes, yes. I have studied their Civil War.” Adi picks up a crust from Helmut’s bread-fort and chews it briskly.

“But look how idiotic they are now. FDR wants to drop thousand of bats over Tokyo to frighten the Japanese.” Hans hisses between his teeth in disgust.

“The bats died in transit.” Adi frowns for even an animal like a bat deserves respect.

“The Americans have so much space in their country, why do they want to come here?” I ask.

“A country never has enough space,” Hans answers.

“Anglo orchestras are not performing the great Wagner but play silly songs as… ‘Yes, We Have No Bananas.’” Magda begins singing in a throaty tone while looking knowingly at Hans.

“Nobody orders sauerkraut in the U.S.” I’m eager to show that I’m keeping up with the news. “And the Allies go around kicking dachshunds.”

Adi finds this hard to believe.

Picking up a cob, Hans asks, “You just bite at it, Mein Führer?”

“Do you have false teeth?”

“I’m twenty-eight, Mein Führer.” His face tenses in disbelief as he flexes his fingers anxiously.

Adi notices minor mannerisms in people. Looking at the pilot’s twitching hands he asks: “Are you impatient with me?”

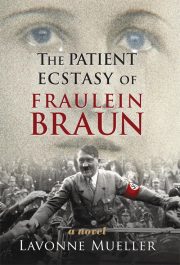

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.