Venice. All those wispy violet cardinals praying in gondolas. Birds posing like ancient tapestry. Since the city is so rich in past splendor, I was surprised its pieces didn’t seem to fit together. Houses built on bridges, crooked streets running off without apparent form or reason, aimless canals. Even their tea tastes of arrowroot.

As Josef and Magda were reading Goethe’s account of Venice in the book Italian Journey, they wanted me to read it, too, but I preferred to read the city on my feet, following holy processions through the narrow paths beside the canals, buying mounds of green olives that I ate with my fingers from an oily paper cone.

That day we came into Venice on shiny black gondolas—our red and black swastika flags trailing over the water in a fan of triumph—we made Venice wonderfully Germanic. Swaying but standing erect, we sang while floating through canals: “So weit die braune Heide geht… gehort das alles wir…”

Italians gathered in the little squares and alleys smiling and waving at us. I had seen pictures of this city in schoolbooks, but the overripe buildings with narrow windows that smelled of fish were an exotic delight that I would write about in my next letter to Mother. My mutter said she would like to have her fortune told in Venice under the city’s ancient weight of so much richness. Her fortune would prove more prosperous under funny square lamps in wrought-iron brackets.

Josef and Magda bought opium pills coated in gold flakes. The light layered yellow glaze was able to slow down the effects of the pills so the results were dazzlingly timed. While the three of us sat on brocaded cushions in a hotel suite, a hooded young man and a girl in harlequin dress both played lutes and gave us massages using dominoes. Rhythmic dominoes were interchanged so that those prancing in all the orifices of Josef and Magda were also prancing in mine. We three were love gambling right in the middle of a city of old churches, cisterns, and gullibility. Having won over Musso politically, we were now trafficking in his pleasures.

Before we met the Pope, Josef prepared us for this splendor by giving Magda and me each a diamond studded live fish attached to a leash. Strolling along the canals, Magda and I walked our fish like puppies. Later, Josef had them dried, and they became delicate pins with little diamond chips along the fins. Adi hates me in baubles as his mother never could afford so much as a brooch, and he would be horrified that a fish was killed, so I could only wear it when I visited my mother and later I gave it to her as a birthday gift.

Since the Pope was not at the Vatican, we met him in a sumptuous villa along a muddy Venice canal that was the second home of a countess from Bologna. Above the entryway, the villa flew a huge papal white and yellow flag. In all the rooms were roses on the crosses, not the dying body of Jesus. This I found to be more in keeping with Adi’s demand for the removal of conventional crucifixes in Germany. Roses make things less religious. Adi said Bismarck was suspicious of the Catholic religion because of its Jewish foundation.

I wore a navy blue dress with large silver buttons. A Countess Bologna servant gave me a black veil. We were treated quite well by the priests as most of them favored us because we were against the Communists and Freemasons and had “Gott Mit Uns,” God With Us, on our standard infantryman’s belt buckle. When the Pope came in, we genuflected and kissed the ring on his thin and yellow hand as Josef snickered silently observing the satin vestments and enormous retinue of cardinals and prelates hovering around in a manner he claimed was an outrageous show of rubrics. He could smell the inquisition. But I was impressed because before the Pope met us, he only ate a simple lunch of boiled onions in cream sauce that was served to him from a Vatican cook on his knees.

With a flashy poisonous lime skirt and tight white sweater, Magda was dressed inappropriately. White above the waist was her pious concession, a mesh sweater with pointed steeples jutting out. She smelled of DDT powder from dusting her pubic hair to take care of crabs and was often in agony, the itching making her wildly distracted. Maybe that was why she addressed the head of the Catholic Church as Mein Herr Pope and referred to the Virgin Mary reverently as “Mamma Mia.” On her head she wore a simple creamy lace handkerchief over the black veil that was provided by a humpback nun who later sat in sulky silence on the step of a faldstool. In full diplomatic attire, Josef kept his chromium-plated Beretta pistol strapped to his leg, hidden under his trousers. Being ironic, he addressed the Pope as Eure Majestat.

Hoping to confirm the rumor of his double row of teeth, I tried to see the upper mouth of Pius XII. But he had a wart removed from his lip that morning and couldn’t smile and scrunched up his mouth in a menacing twist. Whether it was from pain or from his double row of teeth, I was never able to know.

Josef was grateful to the pontiff for many things—for being pro-Axis, for not being admired in England, for the Concordat, an agreement that ensured the Catholic schools would not teach anything against Nazi authority, and for not protesting Kristallnacht.

As Goebbels would tell us later, “Kristallnacht was a wonderful free shopping orgy. How can anyone possibly fault that?”

“And the Vatican Index forbidding books was an inspiration for us,” I offered.

“Oh, yes,” Goebbels agreed happily.

Still, Adi remained annoyed by His Holiness’ opposition to the mercy killing of the genetically insane, and in 1941 finally ordered the euthanasia program stopped because of pressure from religious leaders. It’s a mystery to me why the Church cares so strongly for people who have no brains. My father worked with a woman whose demented 15-year-old son used to regularly chase the family around the back yard with a hatchet. When the SS came to take the idiot boy away, the family was actually relieved.

H-H, as we came to call His Holiness, was serene and distant. Giving a blessing by passing his hand above us, he silently deliberated over each head as if it were a dish of food for him to judge as edible or not.

Josef gave H-H a gift box of fat beer sausages, two sporting rifles with silver inlay, and one Walther pistol decorated in gold that his cardinals took away silently but with smiling faces. Though Josef hated the Catholics, he was grateful for the Jesuit principles set down by Ignatius Loyola that he imitated when it came time to build the SS.

But when I looked into H-H’s eyes, I saw a dreaminess that had no focus on what Germany hoped to do.

H-H seemed more concerned with froufrou statues and altar cloths than any racial laws. Adi had worried unduly that the Church would show active resistance to him. But I could see the Pope would give us no trouble, and Josef and Magda agreed as we waited on our knees just to hear him say something. Anything. With both his hands held tightly to his stomach, H-H looked as if he were trying to keep the heavy-creamed onions he had for lunch down where they belonged.

Magda presented the Pope with a passionflower, placing it on the floor by his portable throne and saying piously that she would never give one to a Jew as the pistils and stamens resembled the Crucifixion.

Josef broke the silence by thanking the Pope for authorizing birthday greetings to the Führer each year on April 20th.

The Pope said nothing.

“We Germans thank you for the non-interference regarding our bombing of Coventry,” Josef said.

Silence.

“You must keep the Vatican illuminated after dark so that the enemy does not attack your churches.” Josef shifted his weight on one knee.

“We can’t supply light at night as the Führer has yet to occupy the moon,” I announced with a hint of sarcastic humor that made Josef grin.

Silence.

“There is a question, Eure Majestat, regarding that small something that was promised from the Uffizi Museum for the Führer’s Linz collection.”

Silence.

“The shelling in Florence besmirched the Madonna by Arnoldi. I want Eure Majestat to know our soldiers are patrolling the streets for her nose.”

Silence.

The German ambassador to the Vatican, Ernst Von Weizsäcker, announced that our special train was waiting, a train run by two steam locomotives and protected at front and rear by banks of 2-centimetre quick firing antiaircraft guns manned by 26 soldiers. Adi had given us his own Pullman number 10206 with its kitchen and bath car. As we gave our respectful good-byes and reached a door riddled with bullet holes, the Pope suddenly stood, put his red velvet slippers together and swayed, his body totally rigid in a huge sweeping circle. He performed this 180-degree turn in silence three times before stopping, then pranced in a flourish through a long arched hallway.

We never learned what H-H meant. However, being shy, perhaps he was telling us he was ordained to circle not only Venice and the Vatican but the globe as well.

For the journey home, Magda requested a separate train car and had it uncoupled and shunted onto a single track siding so that she and her husband could make noisy love inspired by the Pope. Magda claimed that she did 180 degree turns on Josef’s potency for several hours. When they were finished and rejoined us, the constant jolting of the train on the uneven Italian rails gave me no peace and I did not sleep until we wobbled to a heavily braked stop at the Anhalter Station in Berlin.

Now, all that seems so long ago.

With one child in her arms and four trailing behind, Magda sweeps with a regal grandness into the dining area. Walking noticeably apart is Helga who can’t stand the idea of being one of the brood. Hans stoops to the little ones playfully, moving their hands as he sings,

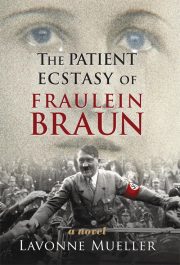

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.