Corporal Rupp calmly leans his small frame against the wall near Adi and stares with coldness at General Keitel. “You read too many diplomatic correspondences, Herr General, such as all those papers detailing the glider assaults of the Witzig’s group. Nevertheless, your presence is necessary for the genius of inactivity.”

Moving close to Götz, General Ramcke mockingly whispers, “I tried to get you a cashmere bathrobe, Mein Führer.”

Götz ignores the malicious mockery.

General Keitel’s ears turn red and his jaw quivers. He murmurs unheard words in fury while flapping the field glasses around his neck.

“To have generals standing around does contribute to morale.” Corporal Rupp gives a half-smile, like Blondi’s half-wag, and his ropy lips hold the smirk for several minutes.

“Didn’t Wordsworth talk about wise passiveness?” adds Goebbels hoping to calm matters.

“You can quote an Anglo at a time like this?” General Ramcke shouts.

“Well, we’re fighting them, aren’t we?” Götz shouts.

“Rupp, your impertinence is outrageous,” Rancke slams back.

“Remember, General Ramcke, I’m not a Nazi. Strictly a soldier,” Götz declares.

Adi likes dissent. It’s what he calls expanding. It makes his officers accountable for what they plan. But he moves on to more important things. “Herr Rupp, as you know, I’m particularly interested in the concept of German instinct and its importance against whatever struggles befall us.”

“There’s only unreason in times of war, Mein Führer,” reports Götz. “My official statement on the matter. You can verify that in the SS Questionnaire of 1934 which I completed at the Brown House in Munich.”

“Doesn’t unreason have to be adequately reasoned?” asks Goebbels.

“Not if it’s spontaneous.” Corporal Rupp tosses written reports to the floor.

The generals scramble to pick up the scattered papers. All this heated bickering, Adi knows, is widening everyone’s thinking.

“Your official reports have nothing to do with what takes place on the front,” Corporal Götz Rupp says.

“Are you saying we lie?” General Ramcke screeches.

“Official reports contain meaningless details.” Corporal Rupp smashes a page on the floor with his foot. “The victor will be the country that no longer has any forms left. We have axed the Church, but we still honor Saint bureaucracy.”

“The front is getting thicker. Every day. We’ll be unable to even cover it with forms. 3,000 km and growing. Anywhere you look, it’s the front. Up. Down. Sideways. Length! Colossi!” As his nose swells wider, Ramcke could defeat Götz by sniffing him down.

“Generals. Let us calm down with a brandy. Courvoisier,” Goebbels blusters. “Mein Führer allows Courvoisier in his presence as it’s Napoleon’s favorite.”

The day the French armistice was signed, Adi spent one full hour at Napoleon’s Tomb in silent meditation. So of course they drink Courvoisier.

“It was wrong to put Napoleon’s Tomb down in a hole, Adi announces. “I wish to be placed high.”

“We must not think of such things regarding you, Mein Führer, our youthful, vigorous leader. Better to remember our Führer’s visit to the Paris Opera Building where you knew more about the architecture than the director and took over the guided tour yourself,” Keitel adds.

“Ah. The French occupation,” Ramcke sighs. “Those were the good days. We nailed the French that time… even getting our nasty hereditary enemy to sign the armistice in the very railroad car used for the surrender of imperial Germany on November 11, 1918.”

“And the glory of the Führer condemning General de Gaulle to death in absentia,” Goebbels offers proudly.

“It was the French military court who condemned him. They wanted Vichy to stay in control,” Götz corrects.

“It’s all the same,” Goebbels claims with arrogance.

“We conquered France for one reason,” Götz alleges. “To force England to be peaceful.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Keitel shouts.

“Are we forgetting the elegance of our Führer in this whole matter? He—not any Frenchman—was the one who arranged for the remains of Napoleon’s son to be moved to Paris to rest beside his father,” Krosigk declares.

“That so-called son was only the emperor of France for two weeks,” Götz sneers.

“Corporal Rupp, I must remind you, it was a carefully planned gesture to have my name associated forever with Napoleon,” Adi adds calmly.

“No need to dwell on France. That’s in the past,” Goebbels states curtly.

Outside the map room, Hans’ beautiful hairy hand is reaching for a bowl on the table, taking a banana and stripping it until the curved firm pulp is exposed. He extends the tip to Magda and her fleshy white arm, looking like the plump rounded stem of a vase, reaches for it. Hans moves her arm away and places two fingers gently on her front teeth, lowers her head and purses her lips so she can only suck.

As Heinz Linge walks by, he sees both fixated on one banana, puts down his tray of tea and sweets, and seizes another banana under peaches and apples in the fruit bowl. His white service gloves are off gray and hard to keep clean from the Bunker dust. He holds out the banana, and Hans bats it away like some enemy artillery directed at his aircraft.

“The German people have proved unworthy,” Adi says. “I could have accomplished something even with a Weimar constitution if it were not for the traitors in our midst.”

“Yes, yes,” I hear Goebbels agree as his wife’s sucking is down one third of the banana. Der Chef Pilot rolls his eyes feverishly as his hand supports the disappearing soft curve. I feel a surge of delight. Banana dramas are hard to find in the Bunker.

“My Führer, more speeches and more parades, more postcards,” General Ramcke offers in a rasping voice. “But no more films like Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. She ignored the professional military. There were only quick glimpses of a few officers. She favors, of all things, the Labor service.”

Goebbels’ voice booms from the map room in a personal shrill grievance. “The Poles flouted the Corridor and went right on wandering down to the sea. They have the audacity to say you lied. Didn’t you straighten up the Eastern border?”

“You can print that in Das Reich. See that civilians get the paper free at least once a week. Announce it on the radio,” Adi orders.

“Introduced with a few soft drums. Then Beethoven,” Goebbels adds.

“The ‘fifth,’” Adi says.

I continue to scribble down their words hurriedly as Heinz Linge steps briskly out of the map room carrying an empty tray while Magda sucks down the remains of the banana’s flesh. With Hans’ eyes closed, Magda licks the heel of his hand for the finish. Then a child is heard crying, and Magda rushes off, the ugly screech of her chair on the concrete an abrupt indignity.

“Did you convince her about the children?” I ask.

Limp and feeble, Hans is in no shape to answer.

Soon Adi will come from the map room for some last minutes notes about our wedding tonight. I watch and wait.

My wedding. I say the words softly. My wedding. This is the day women wish for, dream about, prepare for. When I was a girl of seventeen, my sister and I decided it was time to be women. We were very close then and decided to lose our virginity together. Older by a few years, it was my duty to plot our fate. Gretl was never as pretty or as firm as I was or still am. She hates to exercise. Even when she was just a girl, she would ride the bus everywhere, even to our school that was eight blocks from home. I walked. I could never get her to go swimming with me. Maybe she was self-conscious about her flabby thighs. She never had the good sense to realize that kind of thing can be overlooked in the heat of passion.

Gretl and I shared a bedroom as we were growing up, and when mother made us turn out the light, we talked about our breasts, how they inched bigger each day. I didn’t know then that Adi’s mother died of breast cancer and had both breasts taken off and he would someday, therefore, have nothing to do with mine.

We talked about hymens, all the different kinds—elastic, thick, delicate. Sticking our finger up inside ourselves, we’d touch ours. My sister felt mine—and I would touch hers—all the time evaluating and questioning who was best to break this important barrier. Gretl’s hymen was very delicate, and I had to be gentle when examining her. Mine was very thick, and Gretl could almost punch it.

We were just young girls without any knowledge of seduction, and there was also little money to buy fancy clothes. I saved the gold paper on my father’s cigars—Zigarrenbands—and pasted them around my nipples and Gretl’s. My nipples got hard instantly as I was older and more sensuous. With Gretl I had to rub them with oil until her buds popped out like ugly plugs. Gretl’s nipples have thin black hairs on the end that disgusted me at the time, but it’s one of the reasons General Fegelein married her and why she got pregnant. Recently, my unfortunate brother-in-law was arrested for treason and the first thing he asked for was a barber to cut his hair before he was shot. Goebbels said it was like the ancient Spartans who combed their hair even before a losing battle. That didn’t make Gretl feel any better.

But back in those youthful days, our only worry was what man could perform well on two inexperienced young girls at the same time. We needed technique and energetic tenderness and were jealous of men, who could go to prostitutes. We didn’t have anybody to pay. We thought about saving up enough money to go to Italy, but the language barrier would hinder any verbal enticements. Besides, the Italians, though overly romantic, are not subtle. How could such boisterous lovers ever know the vibrant deep strings of strong Bavarian women from Simbach?

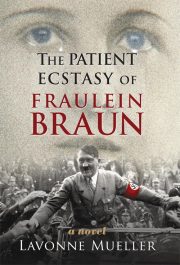

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.