“You can compare Adolf to a monk?”

“Courage is courage, is it not?” Hans takes a sandwich from his pocket. “This bread may have come from a Berlin bakery on Kurfurstendamm. Just occupied. A Russian might have taken the pan from the oven, thrown the loaves on the table. Maybe that Ivan is now on his way to the Führerbunker.”

We both stare at the sandwich.

“Don’t eat it,” I say. “We have good potato noodles and orangen biskuit. I’ll have something to eat with you.”

Walking to the dining area, the chef pilot blusters on in minute detail about a possible breakout. Hans’ adjutant recently left through the collapsing subway tunnels and over Lake Wannsee to carry Mein Führer’s last will and testament out of Berlin. Is not the Führer himself more valuable, more important than a will?

“It’s useless to go on and on about the Weimar years. Everybody knows that decadence. All the crazy art with no logic, no top or bottom or margins. Not even frames. They even stole door knobs,” Hans adds sadly.

We don’t feel like eating. Glistening noodles and vegetable cutlets stare at us from the plate. I think about the armless soldier playing his little tin harmonica with a cigarette still in his mouth. What can it all mean? Why doesn’t the world understand? How can I possibly protect Adi in all this distress? Should I encourage him to take Hans’ suggestion for the breakout?

Magda joins us at the table. Her dress is back in order but one sleeve has a damp spot where the children fell asleep against her arm crying. Jumping up to get her a cup of coffee, she waves Hans away and pours herself a glass of Holzschnaps from the douche bag that she carries in her skirt pocket. Hans drinks from his sour army canteen. I gulp sweet grape juice from the tumbler that has little Nazi hooked cross flags stretched evenly all around the chipped rim.

“Let me take the children out.” Hans begins his campaign once again. “There’s an emergency air strip near the Brandenburg Gate.”

“I can’t let them go without me.” She lapses into her usual nostalgia. “I can remember when we never ate without a printed French menu in the ambassadorial fashion.”

“I can take you out. You and the children. If you stay behind…”

“My husband will not leave,” Magda says firmly. “He’ll perform his duties to the end.”

“They are only babies,” Hans says softly.

“Of course they are babies. They’re mine, after all.”

“I have no intention of forgetting that. For this reason I must save them. I’ve kept planes ready at my underground hangar at Tempelhof airport. I recently flew Prince Viktor zu Wied to safety.“

“My children remain with my husband and me. When the time comes, I’ll take my dress apart. Sleeves. Sash. Collar. Skirt. I’ll throw the pieces in every direction so I won’t leave a souvenir for the Russians.”

Magda tugs at her dress, demonstrating her anger at the enemy. “Mein Führer only claimed what was his. The Rhineland. The Sudetenland. The Polish Corridor. People of Austria gave him permission to annex them, didn’t they? Why do they cry over France? What was he suppose to do, not invade?”

The two of them forget I’m present.

Alarmed at Magda’s outburst, Hans reaches out and grabs her hands as if she were a child having a tantrum. He whispers soft reassuring sounds to calm her. I’m fascinated. It’s a tender moment, one I don’t often find in connection with Magda. As his hands are large and hairy with chappy fingers, I can see why he has control and skill with that airplane stick up in the sky. Before Hans can calm her, Magda’s right sleeve is half ripped from her dress. He whispers war courage to her, his own stories of heroes. Oberleutnant Hofmann, the true patriot we can never forget, flying over and over. Only one leg. Flying over and over. Never giving up.

“A British plane dropped a peg-leg over Munich. They even included a gift tag addressed to Hofmann,” I offer with sarcasm. But they don’t hear me.

Magda turns calm. “Oberleutnant Hofmann was finally drafted to the hereafter, as Rommel was. Though I think we helped Rommy along.”

“Rommel, that sly Swabian fox,” Hans bellows. “What’s this myth about him being a great general? He spent too much time sitting on his heels in camel thorns like a native and no time with his supply lines. He had his ears so close to the ground they were full of sand fleas. He didn’t know what was going on around him.”

“I rather like his ‘Panzer Song.’” Magda begins singing: “Panzer rollen in Afrika vor…”

“And he used planes. You don’t hear about that,” Hans states.

“I heard,” I say proudly. “He flew over the battlefields in a Storch light observation aircraft, landing around his tanks.”

“Who told you that?” Hans asks.

“Goebbels.” It was really Göring, but I don’t want to bring up Göring’s name at this time.

“Rommel was constantly in the front lines. We even bombed him a couple of time ourselves.”

“Didn’t he win the Blue Max?” Magda asks.

“Long before this war,” Hans says dismissively. “Africa was all a sport to him. Open terrain. No civilians. Sharpshooting into the vision slits of French tanks. A game.”

“I miss those wonderful boxes of Magenbrot he would send just to me… such delicious sweet Swabian cookies,” Magda gushes.

“But from the desert, Rommel learned that silence and loneliness are infinite,” I interject, repeating what General Keitel once told me, in order to counteract Magda’s remark about silly cookies. “Is that not valuable in wartime?”

“The real hero of the desert was the German 88 mm, the most effective field gun against tanks in Africa. Ladies, better to think only of hofmann,” Hans brays.

“Of course. Precious Hofmann,” Magda says.

Magda is more sad about Hofmann dying before she could get him in her arms than the fact that he had died so heroically.

Trying to put Magda’s ripped sleeve back where it belongs is an impossible gesture. But Hans tries, the back of his hand brushing across her breast. Though she has calmed from her war fury, she’s now agitated by lust.

“You must eat noodles,” I say to both of them. “A full stomach is comforting.”

They don’t hear me, see me, or know that I’m there. The room has become still. They stare at each other without moving. From the situation conference in the map room comes the faint chatter of Generals Krosigk, Keitel, and Ramcke along with Götz Rupp, Goebbels, and Bormann talking to their Führer. I see them all as the door has been flung wide open because Heinz Linge goes back and forth with trays of cups, tea, and platters of pflaumenkuchen, crullers, and egg pudding to pacify the raving sweet tooth of his Führer. The cakes smell of dampness. Adi doesn’t care, he happily nibbles and gestures with a cream puff, jabbing it into Bormann’s chest of medals and smearing yellow cream all along his top buttons.

“I absolutely oppose the machine gun because it makes close combat impossible. Jet propulsion is an obstacle to air combat. And developing an A-Bomb is so much Jewish pseudo-science,” Adi shouts. “Now a Panzer tank… that’s a superior weapon. One 25-ton Panzer IV has 39,000 kg of steel, 195 kg of copper, 238 kg of aluminum, 63 kg of lead, 66 kg of zinc, 116 kg of rubber.”

“How magnificent is your memory,” Krosigk proclaims, smiling. “You know everything about the Panzer down to its pistol ammunition.” I wonder if the rumor is true that the general still has all his original milk teeth.

“I also continue to read the railway timetable.” Adi begins reciting from memory complicated arrival and departure times.

How long will Hans and Magda stare at each other like two fascinated animals? Who will make the first move? I think about the insect world where sex results in death.

“There! Right there! A formation of tanks are crowded together,” Adi shouts, and he’s pointing to his detailed ground plans with black dots to show where mines are planted. “Can’t you see, Generals?” He says Generals and makes it sound like bums.

“Their white stars are clear to see,” Goebbels remarks.

Götz calls loudly for ordnung. Order! Gunfire suddenly erupts for Adi shoots into the concrete walls to establish himself in the real war. He does this exercise for Corporal Götz Rupp feels it’s important that Adi relive active battle. Corporal Rupp yells: “Grenade!” Adi holds a phantom grenade so real to him that his fingers move expertly to work the pin loose.

The generals back away from the action as Corporal Rupp tells them that warfare is determined by the quick thinking of the common soldier in battle. Animal instinct moves that soldier to decide whether to advance or whether to employ one form of artillery over another. It’s the unplanned, the spontaneous decisions that brings about historic consequences. Things get exciting only when things go wrong, Götz tells them. He gives an example: “Place a grenade on the helmet of a soldier. If the grenade is balanced, he can pull the pin and stand at attention. No damage if the soldier maintains absolute stillness as the explosion dissipates above his steel helmet. But if he becomes rattled and lets the grenade fall… you see, it’s all in the hands of the individual.”

General Keitel is enraged. “Are you saying we should not give orders?”

“You know the old saying: ‘Germans won’t fight without an order.’ However, we can’t rely only on generals. Not even the great German military,” Götz says.

“Can you please restate that in high German,” General Krosigk orders sarcastically.

“Come now,” Goebbels pleads, “we all wish to kill the same enemy.”

“I don’t consider the act of killing so difficult,” Ramcke adds. “One has only to pull the pin.” In his uniform pocket, Ramcke carries a tin of loose gold nuggets that he shuffles with his fingers like worry beads.

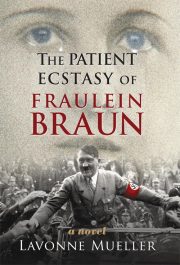

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.