Magda has broad shoulders. But not without help. With boxes full of shoulder pads, she uses them so often she looks deformed, perhaps to show up her husband’s club foot. As if this were a way to get revenge for his flaunting of mistresses. With three pads on each shoulder, she will look at Josef from head to toe as if he were a glob of green mold on a hunk of dying cheese.

Longing to be political as well as sensual, Magda spoke on the radio during the early years of the war, mostly on Mother’s Day. “Produce children,” she urged. “Kinder, Kirche, Kuche.” She called her speech “Babies, Mothers: Mothers, Babies” using this title because she didn’t know which of the two words should come first. Exalted in being a fine German mother, she hoped to inspire other German mothers. She also publicly announced to the world that she would never leave the Führer’s side.

She stops babbling about her past triumphs, realizing there will not be another radio broadcast to proclaim her loyalty. And she hasn’t delivered twins or certainly not many twins, something the Reich desires of all married women.

“On your wedding night, Eva, you will… will finally get what you want.”

“How do you know what I want?”

Magda has a way of projecting her own desires on me. But what else can she do? She’ll never have Adi the way I have him. I feel sorry for her from time to time.

“I know my Führer well enough to realize he can never fully give of himself. Except to the Reich.”

Magda learned the military way of speaking curtly, her head up, standing straight. That’s her method of keeping some of Adi to herself. Wasn’t she part of his official world?

“Oh, I’ll get his full self.”

She was startled by my confidence, maybe even fearful of it and changed the subject to politics. “This hell going on up there is only a test,” Magda pronounced as we both walked to the dining area for coffee to steady her large dose of Veronal. “A divine test. They’ll all know that in the future. The world will know he’s right. We will never lose for it cannot happen because it must not happen.” The generator was still and there wasn’t enough air to stir the blond tendrils of hair by Magda’s forehead. She looked like a woman in a wig. “What do people expect from peace when they will have to do everything? In wartime, we have a great Hitler to think for us.”

15

ON TOP OF THE BUNKER, Bormann receives Hans Baur who comes roaring up in a motorcycle sidecar wearing a leather coat and his Golden Badge of Honor to signify his early party membership. His camouflage cap brashly on one side over his ear, with a firm vulture beak of a nose, he struts into the room interrupting Magda and me for another of his breakout plans.

“Please convince the Führer that he must leave for the Berghof. Now! I can still fly all of you out.”

“Hardly the optimism our Führer demands,” I remind him.

“I can be optimistic only as a soldier. As a simple human being, I despair of what is being done to my country. I must fly him out.”

“He won’t go,” I say.

When Josef Goebbels comes in, Hans Baur starts on him. “Herr Goebbels, the enemy shoot children sleigh-riding. This is not a noble war. I can fly out your little ones.”

“Magda put them down for their nap. Come, have onion cake in the dining room. It’s from the Rheinpfalz.” Josef stares upward as if the city of Rheinpfalz is visible on the ceiling.

Hans Baur refuses onion cake from the Reinpfalz. He has sandwiches in his pocket. All the pilots I have known have sandwiches in their pocket. He wears a dignified black uniform of the foreign ministry that looks very much like the SS. His cousin got him the uniform. Better not to be identified as a pilot, especially the pilot of the Führer.

“Do you think I’m not careful with children?” Hans snorts.

“You’re the Führer’s pilot, what more is there to say.”

“There is quite a bit more,” Hans says more politely. “I’ve been flying since the age of sixteen, got my aerobatic license at seventeen. I’m the only soldier who reported to the Luftwaffe with my own aircraft.” I know he wants to make sure Goebbels realizes that a breakout would be in most experienced hands. Assuring us that he has good eyesight, Hans states he can see anything no matter how far away and can fire from the clouds down to the treetops if need be.

“You must be a good hunter as well. Have you been with the falcons lately?” Goebbels asks.

“I have no time for that,” Der Chef Pilot tells him.

Hans has no dueling scars. He carefully avoided them at the university because most dueling scars are rumored to be self-inflicted. But for Magda, these wounds—real or not—are attractive. As a child, she etched a line on her chin with a potato knife. Her mother took her to a Swiss plastic surgeon to get it erased. What man, her mother said, would marry a woman with a self-imposed scar on her face.

“And your girlfriends,” Goebbels asks smiling. “Are they all well?”

“Women are virgins till we fly them over the Reich.” When excited, he answers in broad Swabian.

Both men laugh loudly and slap each other on the back. Goebbels doesn’t know that der chef has flown Magda over Munich.

“So you have been very busy, no doubt,” Goebbels says. “One after the other Fräulein going over the Reich.”

A pheasant flew into his propellers yesterday. Bloody feathers smeared his leather helmet when he landed. He laughs, but I know those feathers made him think of Magda in her splendid hats. Everything makes him think of Magda.

Hans Baur is serious knowing there’s not much time left, not for him or for all the girlfriends he has carefully hidden in towns and villages. His country is drowning, and he has only one objective—to rescue his Führer. “Why won’t Mein Führer leave?” Hans moans to Goebbels over and over. Being so depressed, he has to go to the half-bombed Tippel Pub on Linienstrasse every night singing melancholy songs: “Es geht alles vorüber, es geht alles vorbei. All of life goes by. All of life has its time. After one month comes another.” The pub musician pounds on a war-damaged harmonium with lost keys, and everyone has to hum the missing notes.

Since flying the wounded to hospitals, Hans plays Skat and 24, 40, 48 Grand Slam with other pilots at the now underground Kustler Eck, drinking too many stone mugs of beer. How is it possible for him to fly all of Germany out of Germany because that’s what he feels he must do. Last night he heard a soldier with no arms playing the Beer Barrel Polka on a little tin harmonica, a Manoli cigarette in his mouth. (Hans marched off to war one September morning in 1939 to that rousing polka.) A nurse placed the harmonica in that soldier’s mouth and he puckered in a special way to keep the harmonica and the cigarette both between his lips. But the tune now sounded mournful.

Magda saunters in smiling with that secret way she has, her eyes heavy lidded, the ends of her lips slightly dipping downward. Hans is happy to see her so casually dressed with one shoulder bare as the children no doubt tugged at her clothes as she put them to sleep. Quickly greeting us, she then goes back in the room to her children.

Bormann enters looking tired, raw, and resembling a fat line of ground beef from a very large meat grinder. “Hans, what’s the news?”

“What news?” Hans asks innocently.

“What is coming at us?”

“Mostly mortars, Herr Bormann. Though only yesterday, I emerged from cloud cover to go directly into a fierce rage with five enemy crates. I hosed them with shells, but got hit in my engine cowling panels. Luckily my plane flattened out and made a perfect landing on its belly in a cabbage field.”

“Keep track of the numbers. Record it in triplicate. The Führer likes numbers. By the way, I admire your part in the Rosarius Traveling Circus.”

“Yes, we learned a lot about the enemy as you know since our flights were comprised of all the airworthy captured planes we could find. I’ve become familiar with enemy techniques and now if the Führer will just let me…”

“Yes… the Führer appreciates your efforts.”

Bormann doesn’t acknowledge Goebbels’ presence or mine, quickly darting into the map room.

“He didn’t give me time to explain the breakout,” Hans says.

“It’s useless.” I pat his arm.

“She’s right,” agrees Goebbels.

“The breakout must come now. Now! What is the Führer thinking?”

“He’s thinking of the rotten Weimar government and still carries an old letter stamp in his pocket that cost tens of billions of marks. We drank Weimar coffee as it doubled in price while we drank it. He has a lump of coal on his desk. Can you forget that the Weimar government had to back up currency with coal! What else can he possibly be thinking? If you both will please excuse me, I must now commit map perjury for the Führer’s morale.” Goebbels enters the map room with an early-war flourish.

“I had no intention of offending the Reichsminister.” The chef pilot sits on a trunk that wobbles as I use it for a table not a bench. Two soldiers found the trunk outside the rubble of the Friedrichstrasse Train Station, and I had them make little legs that they attached with wooden screws. “What do you scribble all the time, Fräulein?”

“Memories. Delights. My life with a genius.”

“Why?”

“To mark my existence with the Führer. Who knows that truth better than I do… about how honorable and brave he is?”

“Little monk, little monk, you are taking a hard road,” Hans recites.

“Whatever does that mean?”

“That applies to our great leader—the famous words of Frundsberg to Dr. Martin Luther before the Diet of Worms in 1521.”

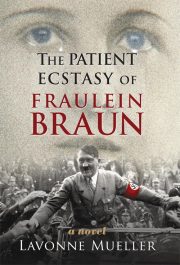

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.