I am carefully reading books on a list Goebbels gave me, but I was disturbed half way through War and Peace. The book torments me. It’s easy to see that the novel is about Napoleon’s conflict with Russia. When Napoleon retreats from Moscow, I cried. Not for Napoleon but for Adi.

I can’t read all the time. When Magda and the children are sleeping, when everybody’s in the map room and even the stove isn’t bubbling with meals, when I have absolutely nothing to do, I find other ways to fill the hours. I lie down in my room only I can’t sleep because I know the afternoon is Adi’s busiest time. I sometimes put on his fur-lined military goggles to feel a hint of his face. Listless and useless, unable to help him, I think of the unseen murderous blue sky above and that forces me to burn myself alive, like a sunflower yellows itself alive. Moving my hand slowly between my thighs, I linger, sink deeper to find that dark tribe smelling strongly of the earth. I rub slowly. I’m foamy. A sharp smell of wild apricots. Faster. I’m crusty in this imitation of a noble act that will be fulfilled on my wedding night. Ready to explode, my tender little knob that Adi calls the Old Silesian is forever primed, this grandeur and nobility of my body. Arab women Goebbels met had their Old Silesian surgically removed when they were little girls thus becoming wooden dolls and feeling hardly anything but able to continue love making in a mechanical way hour after hour with nothing but sandal oil to help them along. I can’t touch my “old silesian” too much as it will go off right away and then I’ll have nothing left for the remaining hours. Patience and control, like a good soldier. Never firing off at will. To spark at the right time. Let the “old silesian” stand at attention, let it quiver and be in amazing agony without rank. Think of things. Anything. Just to keep the “old silesian” simmering, never to boil until the afternoon dies. Time. Take up the slack of time. Thinking: Adi, when I first met him, his clean uniform showing the sharp creases so carefully ironed. Those military buttons, each one standing erect, refusing to lie flat against his firm chest. His straight proud body, unlike any other, complete, everything perfect. His form so honest, so intelligent, not only what the eye can see, but underneath, beyond the eye, toward purpose and mission. His great German objective in spite of generals who walk on maps not roads, harping on colonies and tanks. Once I saw Adi’s name scrawled on a stone wall, and I glowed with happiness and carved my initials beside it—E.B. Whenever Adi wrote me a note, I pinned it to a chain and wore it around my neck. Now thinking… silly Goebbels cured actress-lovers of snoring with drugs. The Duke of Windsor loving that woman who Goebbels said was like sticking it into a tree-crotch. My swimmer’s swagger Adi loves. Feather grass, moss, lichen at the Berghof. Singing,

“I’m a good loyal Nazi

A good loyal Nazi so keen

On my way

To Nazi Berlin

Where I can now be seen.”

I use an old church chalice as a vase and stopped making slash marks on the concrete walls to designate the days passing. That morning at the beauty shop when Adi was preparing for Barbarossa, an operation so big that even the people in Berlin knew, and the hairdresser who heard rumors of who I was wouldn’t curl my hair for fear he’d frizz me into reprisals. Awful pain of my second inoculation against typhus in the Bunker. Yesterday, roast hare for lunch, killed by a landmine, the fat juice from the hare’s breast spilling grease on my chin. Now I’m rubbing harder, urging a pattern of dew, tamping down. The wood orchids by the Berghof. First thing I remember in life, standing up in my baby bed waving my arms to be picked up, but mother’s in the next room scrubbing the floor. Tiny wooden slats hem me in, and I want out of the crib. Mutter’s wash bucket scrapes the floor. The milky white floor. Flinging my arms over and over to the empty air, I realize even then that I hate waiting. Short curls in a globe below my firm belly. This is the silky hair he feels. I ease in, stop at the crevice, glide back and forth. Strategy is nothing, of little importance now. There, there, so tender, so eager. And not even willing it, I pop. And the Bunker sinks into night. The afternoon is over.

I love being spontaneous, imagining he’s pleasuring me, never stopping to reason things out. Never avoiding my immediate impulses. That’s the way Ilse was.

I was once good friends with Ilse Hess who is much more down to earth than Magda. Ilse can laugh at herself. What makes me think of Ilse now? Maybe cracks in the walls that spiral out into cloud shapes. But clouds are only made of water and drip like concrete and are as much a false illusion as any fantasy, even the romantic memories I have of Ilse. Her handsome husband—in his blue-gray uniform, dark blue tie and insignia of a Hauptmann—liked Ilse to go with him when he was flying. They ate doughnuts with melted glazes and Kokosnussbonbons, their lips rimmed in chocolate, swooping over fields and gliding down low to scare the cows. Screaming as the plane dived and seeing her frightened made Rudi feel manly. We laughed at her acting in the sky. Ilse wasn’t afraid of flying saying, “It’s dead birds who never fall from their nests.”

Hess. Once the Führer’s deputy. I loved his thick Bavarian brogue. But what a terrible thing he did to Adi by going off secretly to make peace. What was he thinking? Adi was once so fond of him. Hadn’t they both been wounded in the First World War? Ilse told me Rudi still had little pieces from an exploding shell in his left hand and upper arm. She wanted him to have a surgeon remove all that, but he refused never wanting to forget the Battle of Verdun and how General Von Falkenhayn had been so glorious in leading him and the others along the River Maas. But Ilse couldn’t help but cry when she saw Rudi’s scars. They made love that way, she crying, he trying to comfort her. Soon he was the aviator and went up. As he made love like the Frontschweine, those still alive from the great bloody infantry, there was no comfort. It was trench-love, she said, not all together unpleasant, but it was rough. Not that he could help himself when he wore his black leather flight suit and kept on his parachute harness. Wearing fleece-lined flying boots, he used them to pry her open. She acquired plenty of bruising. Many were lavender over time, and now with him in some British prison, lavender blemishes are all she has left. So it was good that he gifted her in whatever way he could.

I have no contact with Ilse at present, but she must lead a dreary, lonely life.

When I mention to Adi the slightest thing about Ilse, or even Rudi, he naturally gets upset. I always have to remind him that Rudi was a corporal, too, in the infantry.

“He was never a corporal for long.”

“But Adi, Hess was with you in prison.”

When agitated, Adi bites his mustache. “Did he appreciate that!”

“Landsberg Prison. Cell 7,” I say proudly. “You were the admired one who got to keep a light on until midnight. The warden became a National Socialist because of you.”

“You never forget anything,” Adi says in admiration.

“And to think you once dictated Mein Kampf to Hess.”

“He added some lines of his own in Kampf. On the sly.”

“Even then he was a traitor,” I add.

“In spite of that, my book sold over a million and a half copies. And you, my Evchen, are probably the only one who has read every single word of it,” he says lovingly. He pauses for emphasis. “You could be a man. It would be a lot easier for me.”

His words make me deliriously happy.

“Regardless of Hess’ stupidity, I foolishly helped him all the time. Even got him to marry that fat wife of his.”

“She’s not fat, Adi.”

“She ate lunch every day at the Osteria Bavaria Restaurant which serves huge platters of beef.”

“In spite of the beef, you got him to marry Ilse?”

“She had spider veins on her legs, but she was the daughter of Oberstabsarzt Dr. Prohl.”

“She probably really fancied you,” I teased.

Adi gave a sultry smile. “She got as close to me as possible. I visited them often at 48 Harthauserstrasse.”

“Now he’s in prison,” I say gaily. But sometimes I can’t help but miss Ilse, especially her stories of trench-love and how she and Rudi use to scare the cows.

14

A SPANISH CAPTAIN LOPED THOUGH THE BUNKER. It’s amazing how international the Bunker can be. Rather short as Spanish men tend to be, he was nevertheless handsome in boots as soft and supple as Sunday gloves. Thick black hair curled up above sled-runner epaulets. He insisted that he see Adi. Bormann made him wait for two hours because the Führer was lunching with his secretaries. The captain waited patiently, all the time tapping the tip of his boots with his whip. If Spain hadn’t remained neutral, perhaps Bormann would have got the Führer to shorten his meal. Adi never eats much, some chilled asparagus and hardboiled eggs. Most of those desserts he craves come with his linden tea in the late afternoon. Spain did give us some volunteer troops because Adi helped them in the Spanish Civil War.

When the captain went topside for a quick smoke, I followed him, eager to sneak a few puffs myself. He offered me a hand rolled cigarette, but I refused for I knew the paper around this hand-rolled cigarette was sealed with the captain’s saliva. Who knows what foreign germs were hidden there.

Spain can do more than give us one little division, so when I let the captain privately join me in my quarters for lunch, I permitted him to clasp my two hands. His legs wandered if his hands could not. I pretended not to notice his superficial indiscretions because he talked endlessly about Chamberlain in the newsreels who pranced around with an umbrella while our Führer strutted like a powerful European player. Being a cavalry captain, his thighs could do things to me that his horses probably never had much interest in. With only one division, I couldn’t let myself be amused for long, so I abruptly pulled away as he grunted and happily released himself into his Spanish yak underwear.

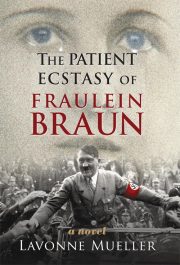

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.