Why am I chosen? Chosen for these last days to be constantly within his reach, to hear all his stories, over and over, a litany that is more dear than any I have heard as a child whispered about the saints in church. His mother waited for him with steaming tea each day after school. Klara would stare at the clock and know exactly when he was leaving the school door, each block at each minute, counting the seconds until he arrived. One day he was late. Having borrowed a book, he promised to return it that very day. His word was his honor, and he walked five miles to the lender’s house while it was raining. Cold, wet and sneezing, he arrived home explaining why he had deprived her of two hours of himself. She threw the teapot out the window into the backyard and smashed his cup. This from a sweet calm woman who rarely raised her voice. Then she composed herself and fitted all the pieces of his cup carefully together placing it in front of him. Adi said he wanted to write an opera about it.

13

KLARA LOVED HIM MORE THAN ANY HUMAN could or would love another human. His happiest years, he said, were spent in Linz at Humboldtstrasse 31. Klara was brave and good, and he learned compassion from her. He would catch slowworms that were chalk white and nice to touch, spongy like his mother’s legs. He never let his friends chop those worms into pieces insisting they use bread for bait as he was eager to save any life he could, especially a life of such prehistoric value. For killing worms would be like killing one’s ancestors.

He and his mother found joy together in simple things. They watched the Kaiser speeding by from Potsdam in his shining black automobile. When Adi was quarantined with scarlet fever and had to stay in the hospital for three months, Klara stood outside the building and could only wave to him at his window. She came every day, even in high winds and storms—all day long only going home at night to sleep. At age ten, he played with a Schnauzer dog that belonged to a girl named Inge who lived next door. When he was 15, he dressed the bust of Wagner with his only cap and his mother’s good wool scarf because he heard Parsifal for the first time. He and Klara walked the streets of Linz chilled without a hat or shawl. That didn’t stop him from sketching all the flowers held by maidens in Parsifal. Such flowers were vaulted and protected in a cathedral of sound.

I’m not jealous of his mother because it was Klara who gave him to me, struggling with the pain of birth when he was born on April 20th in the small town of Braunau on the River Inn that is the frontier between Austria and my beloved Bavaria.

His loving mother would board a crowded Linz bus clutching little Adi’s hand, glaring from one passenger to another shouting: “Can’t some one give this young child a seat!”

Klara was tough when it came to her son. He speaks of her proudly, and she makes me think of a shark that can still bite into your leg after being beached on dry land for many hours. It’s not that she’s stern, just wonderfully strong.

If Klara were still alive, she’d be down here in the Bunker with us the way I wish my mother could be.

The Bunker world is more mine than any up above… drinking coffee with officers as they beat out tunes on their cups with a spoon, talking to Adi when he first emerges from the map room, getting literature and painting lectures from Goebbels, exchanging ideas with the runners who come in and are out of breath and drop down on ammunition boxes waiting to talk to their Führer. Everybody is astonished at how much I know about the war and its strategy. “All depends on General Busse’s Ninth Army. He won’t permit all Berlin to be captured by the enemy,” I state.

I can say things to Goebbels that I would never say above ground: “Even if the Russians finally occupy Berlin, I’ll still be happy for I’ll have Him then forever and ever.” When I say this, Josef Goebbels frowns but somehow understands. The Bunker has made us all more sensitive. If you’re very close to war, as we are, you get overly tender. It’s like being wounded.

As she was boiling soup in the kitchen, I asked our cook if I could on occasion call her mother. She’s only five years older than me and from the silly Rahnsdorf district of Berlin, but it’s difficult to be down here without my mother. So for the last hour, I’ve said: “Mama, more coffee please. Mutter, are there any eggs left for lunch? Mutter, I want something special for my wedding dinner.” But she’s only Fräulein Manzialy who works on a wooden table chopping meat and vegetables, the table wobbly but as enduring as any soldier in the Bunker.

I ache to go up and flaunt myself through this once forbidden city of Berlin. I want to scream to every man, woman and child that I’m going to marry the Führer.

Underground, when there’s no sky above, you think of many things. Sunday is no different from any other day. A dreaminess is all around, but that doesn’t mean the atmosphere is less vital. There’s Adi’s family—his valet, cook, secretaries, doctors, adjutants. Making fun of Adi’s personal entourage, Goebbels calls them the “chauffeureska,” but they’re all necessary and I’m fond of them.

I “read” the Bunker. If the tables and chairs rattle, it’s a medium attack. If only the walls shake, it’s not nearly as bad as when the ground bucks in a maximum hit.

I “read” other things. Everyone coming in wears phosphorous buttons on their coats, tiny round lights to help them find their way around the streets at night. There are ten straight-back chairs placed Italian style along the wall outside the map room for those who wait to speak to Adi, people who have many different ways to show their anticipation. Diplomats look stern, facing each other in little groups. Newspaper people are casual with their legs sprawled. Flexing their arms nervously are civilians. All act similar in entering and leaving the Bunker, more hopeful when entering, more wary when leaving.

When I’m eager to learn more about the war, I choose an old officer like General Korseman. Since he has no need of promotion, he’s less guarded and talks more easily.

“Fräulein,” he would say, “how difficult it is when bombs go down 50 tons a minute for 45 minutes in Hamburg. Americans are also dropping leaflets that state, Das war Hamburg. Imagine: This was Hamburg! Now those papers floating down say, ‘this was Germany! We forbid anyone to touch the leaflets for they could be dusted with poison.’”

“We lost one-eighth of our industrial production. That’s 30 less U-boats a month from the destroyed Hamburg Howaldtswerke shipyards,” I add.

“Yes, Fräulein. You have a remarkable mind for important matters.”

“But the Führer has injected concrete into his staff’s morale after Hamburg with strong speeches to uplift us all. When he speaks and sways, you can see the people sway with him. If he leans forward, they lean forward,” I say proudly.

Besides talking to officers, I also deal with what I call “beseechers.” A distinguished looking civilian or courier will pull me aside and make a request. “Fräulein,” they will say, “I wish to talk to the Führer.” Taking out a piece of folded paper, they ask me to give it to Adi. It would be about pardoning a Jew, a suggestion for the war effort, or the invention of a new weapon. They look for any way that takes them into the inner circle. I smile and ignore their pleas.

The Wehrmacht has a system of proxy marriage for soldiers at the front, and two lieutenants came happily into the Bunker one day on their way to the northern sector to inform Goebbels that they were just married. Their intended wives back in Leipzig went to the local registrar and took the marriage vows with their hands upon a steel helmet. It was all very romantic. Goebbels rewards such soldiers with chocolates, an autographed copy of Mein Kampf, and a sturdy pat on the back. The grooms refused to eat dinner with us for a soldier is warned never to fill his belly before battle. Shot in an empty stomach is better for survival. And off they went singing,

“The sun shines red, get ready

Who knows if it will shine on us tomorrow

To the machines

To the machines

Comrades, there’s no going back.”

Psychics come down to make Adi’s chart or read his cards. (It’s rumored that Churchill hired an astrologer to find out what Adi’s astrologers are predicting.) But I have no use for astrologers. Adi is my present and my future, and there is no need to consult anybody else. One psychic told me that when the Führer shuffled cards for a reading, it was the weakest shuffle ever seen. “He’s war weary,” I explain with irritation. “Can’t you even read that?”

I study the soldiers who come into the Bunker. They’re so easy with violence, scraping the mud from each other’s uniforms with their bayonets and often singing,

“They say we shot our mothers

They say we shot our brothers

They say our cousins, too

For we are never through

Oh oh, die

Die you bastards, die.”

Goebbels gives us lectures on new things like psychiatry. I study paintings from his collection that he keeps in a metal fireproof box and learn about cities and countries from Adi’s generals. Each day I talk to diplomats and commanders. I decorate, plan lunches, look after my clothes, exercise, and play with the Goebbels children.

When there’s water on the Bunker floors, Magda and I make small paper boats for the children to float down our own little Spree. Goebbels brought in an old motor tire, and we roll the little ones inside it along the walls as they scream in excitement. We have to improvise games as Magda let the children take only one toy each to the Bunker.

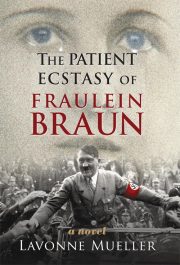

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.