“But how exactly is it going in Russia?”

“Garrison tactics. The enemy ceaselessly moving from village to village.”

“Is that good?”

“You easily win over those peasants with a fist of salt. But Fräulein Braun, that country with its everlasting distance hates us. Ice. Snow.”

“We have ice, snow.”

“Not like Russia. It’s maddening how those Reds never go into assembly position. They attack from their infantry columns wearing white camouflage coats—coming at us wave after wave. They don’t even have enough military etiquette to use proper strategy. And hordes of them get by on so little—bread crusts, raw vegetables. Six soldiers to our one obeying without question in their hideous Slav-Asiatic manner, using wind and snow to their advantage by employing ammunition sleds. Though below zero weather turns itself on them, too, as many of their wounded freeze to death in Marxist hospital beds. Civilians leave Moscow on crowded trains—hanging on the outside frozen stiff.”

“They get the same frostbite we do,” I offered.

“But in their country, frostbite is a punishable offense—considered avoidable. Stupidity should be punished.”

“General, is not frostbite avoidable for us?”

Reverting to von ways, he took out a carved ivory pipe with the stem of a deer horn from his small sailcloth haversack of provisions that every general carries. “You might ask that question to our Führer. He’s much too kind hearted toward our troops.”

“But isn’t that good?”

“The Führer should not have let Heydrich—chief of concentration camps in conquered lands—continue to drive in an open, unarmored vehicle.”

“Heydrich disobeyed the Führer and thus was assassinated,” I said.

“But we lost a good man. And if we continue to be soft, we’ll lose more.”

“Still, don’t you think it’s best to be especially humane to our troops?”

The general prattled on, referring to the Führer’s Nacht und Nebel, cover of darkness. Germany, he stated, had to sometimes imitate the enemy’s undue brutality. Chivalry is a silly dream when a soldier faces the ruthless enemy. British Secret Service crime methods are alien to Germans. Nevertheless, Germans must learn from them. It is the duty of every soldier to remember the words of the Führer: Terrorism can only be defeated by Terrorism. “My dear, do you know how the Red Army clears away a mine field? By sending their men over it in tight formation. That’s how wars are won.”

“Won, you mean, by idiots?”

“Idiots who don’t know what decent thoroughfares are. All their primitive cobblestones injure our horses.”

“Cobblestones? For the main roads?” I asked.

He puffed on his ivory pipe with urgency. “Whatever those Ivans build are shoddy imbroglios. We can hardly do a decent 35 kilometers an hour. If they only had roads like France, an equally dreadful place except for roads. But carts have been found that can be pulled by Russian reindeers. Our men tried to ride reindeers, but those creatures have weak backs though they do possess strong shoulders.”

“One has to admire strong shoulders,” I mused. But Keitel had no reason to smile. He was rubbing his back against a beam. So even generals get infested with bugs.

“Their antlers sway along the road. It’s soothing for our infantry to watch while they’re enduring temperatures fifty below.”

“It’s something I can write to my mother about, Herr General.”

“There is much to write her about.”

“You mean… like the Tolstoy thing?”

“Whatever do you mean, my dear?”

“I was told we set up quarters at the estate of the late Count Tolstoy.”

“Yes. Yes. Infantry Regiment Gross-Deutschland. They were quartered there. Not in the main house but the museum. Commander Guderian’s men didn’t burn one stick of furniture from the estate. He only used wood from the nearby forest.”

“I think that shows great cultural respect.”

“My dear, do you know how we were rewarded? They laid mines around the grave of their greatest writer.”

“General, as far as I know, no German soldier was blown up by Tolstoy.”

“Quite right. Quite right. And that reminds me, there’s a joke among my soldiers: Adam and Eve were the original Communists. They had no clothes but fig leaves, had to steal apples to eat, and couldn’t leave the place where they lived. And thought it was all a perfect existence.”

“If they were in love, perhaps it was.”

“You give them too much credit, Fräulein. Love? Those filthy commissars? Who lack all the etcetera of strategy? It will take Germany years to get that country in good shape. But let’s think of some good news. I just made the Führer smile. Our soldiers found a statue of Stalin in a little village and beheaded him, then cut off his legs. He went from 9 meters to 3.” He chuckled. “A war isn’t worth it if you’re miserable. A struggle should not be unhappy. Enter combat with pleasure or why bother. I remind myself often of the Anschluss and our triumphal entry into Vienna… though I was against decorating our tanks and trucks with garlands. It’s enough that we entered Vienna without carnage.”

“It was a great day for all of us. The torchlight procession. Excited and happy people.”

“My dear, I was carried to my quarters by the Vienna division of the Austrian Army. My buttons were plucked from my greatcoat as souvenirs, an event equal to decapitating Stalin.”

In my next letter, I tell my mother what happened to Stalin’s statue to cheer her, but she’s not impressed.

“With the silk shortage I worry about your underwear,” Mother writes. “How can a woman keep a man like the Führer with cotton underwear?”

Before the war, I was fashionable. I used to wear silk panties, half-slips of watered satin, pink chiffon bed jackets. But the war took those away. Adi is stoic about this and eager that we conserve silk for parachutes. As he slips off my cottons in good spirits, he’ll remark, “What does it matter? The units of my elite Der Führer Regiment don’t own simple cotton undershorts. They go bare.”

“The big burly Der Führer Regiment that took part in the occupation of the Sudetenland?” I ask playfully.

“They are conserving cotton for bandages. I do worry as bare skin against wool trousers can chafe a soldier’s thighs.”

“Don’t you worry about my chafed thighs?”

Adi arched his eyebrows in surprise as I stood before him naked shielding with my hands all the ugly lines from the coarse material, especially the ridges stamped on my stomach. “See what cotton does to my skin.”

Taking my hands away, he admires the creases. “Ah, my precious Evchen, little pink tank tracks. My decisive weapon. Tanks! Once forbidden to me by that fiendish Versailles Treaty. Shall we wet them with honor?” He takes out his genius and sprays me. And I’m grateful that his very life’s necessity is running down my thighs. If I can’t have silk, there are sturdy fingers when he’s finished, thrumming his dankness into my pores as I say over and over… I love you. And he says over and over: “My darling weapon, my sweet grenade.”

He has seamless hands. His mother made him knead the bread when he was growing up. I think specks of dough are still in the creases of his knuckles plumping out the lines. What looks like dough is under his nails making white crescent shaped cuticles. Everything on him is matched and lined up as if marching in a shop-floor excellence. But I wonder, does the blood in his body know which hand or leg it belongs to?

His thumbs. They’re two little Fritzes. Wiggling. The left has entered me, a substitute for what I patiently wait for. And I think of Magda in her proud straw hat with poppies hopelessly longing for the Führer. Hats are not rationed, so she flaunts them… having no conscience about her many flashy rationed dresses.

Goebbels once told me that a conversation and a night out with the Führer was even better than an evening with a first class whore. So Josef looks at me in subtle envy for that special closeness he can never have with Adi, an intimacy that only I’m allowed.

Last night, when Adi cupped my face like a child, when I was every child he ever held like that, he asked me to marry him. This was a humble moment. I told my mother it was a “cotton” moment. He held the brush with “EB” that he had given me and rubbed off the “B” with a nail. Then he scratched on an “H.” I held the brush next to my heart.

I stripped to my coarse panties, and my bra hung unfastened from one breast. That he would take no notice of one breast exposed was just as usual as it would have been if two breasts were exposed. Looking at me with sweet coldness, as if I were a picture that had not come into proper focus, he motioned me to take those things off, as if my panties were cheap beer rags about to come in contact with his closest self. Fear nestled in my stomach. I sensed being a flank or hindquarter, a hide, a carcass broken down into cuts. But fear did not stay long for he smiled and leaned over me and put General Weidling’s monocle down there so that my tiny cave could look at him in wonder. I held the pose, the monocle perched in those moss udder lips between my thighs. And just at that moment, he cupped my face when it was the little face between fleshy posts that ached to be touched. “We’ll marry,” he said, the coldness gone. His voice fell on me like strings of sweet peas and other vine-flowers and I smiled, already a housewife in my contentment. I wanted him to say it again and again, but that was not his way. No, he wouldn’t say any more as Dr. Morell, the old Huguenot, had injected him with caffeine so that his whole body twitched though his face remained rigid with eye spasms. His balance was off from the damaged membrane in his ears, that terrible assassination explosion coming between us. Wrapping his twitching left arm around the bedpost, he lowered himself down to take the monocle out with his lips, spitting it on the floor before his tongue found me again.

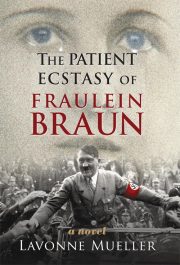

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.