“Russian tanks shoved us back to Zulz,” Goebbels continued. “Our generals should never have allowed the Russians near there.”

“The only good general is Russian. General Winter,” I said.

Adi smiled, what Goebbels called a DaVincian smile. “When asked what kind of generals he liked, Napoleon said… lucky ones,” Adi announced.

“Our Führer Directive Number 33 said Bolshevik officers are to be ‘shot out of hand.’ And rightfully so as even Blondi is much smarter than a Russian,” Magda offered.

But this made Goebbels angry for although Russia was primitive, it still was a vicious opponent and not to be dismissed so easily. Becoming flushed, even his nose reddening, he snapped that it was the Lhasa Apso that protected emperors. As if Magda or I cared about any insult directed toward Blondi.

Pleased that Magda remembered his Directive Number 33, the Lhasa Apso remark didn’t annoy Adi, his gaze a controlled neutral. Facts are facts. “Just fifteen days after mating, Blondi’s embryos were attached to her uterus.”

“Thank goodness it happened quickly,” I amended. “Who can stand loose embryos over fifteen days?”

“One can hardly believe such a miracle.” Magda picked at cabbages as if hearing about Blondi’s uterus was so momentous that the mere idea of sinking her fork into food would seem trifling.

“A dog was Wagner’s muse,” Adi declared. “Little Peps was the co-author of Tannhäuser.”

“Blondi is superior to all those pictures I’ve seen of Patton’s white and ugly bulldog, Willie,” Magda announced.

“Willie! That ridiculous bulldog! What would you expect from a bombast like Patton,” Goebbels added, eager to establish his loyalty back to Blondi.

“And how are Negus and Stasi doing?” Magda’s tone was challenging as she hoped to make me feel guilty for leaving my dogs behind. I didn’t want to bring them to the Bunker. Taking care of Blondi is enough, so I gave them to my Uncle Alois to watch.

“They are sweet little carpet-sweepers,” Adi said of my dogs because of their short legs. He was smiling.

“Negus and Stasi are running happily in Uncle Alois’ yard,” I announced proudly.

Adi suddenly froze for fifteen minutes—completely motionless, his spoon to his mouth. Goebbels stifled a yawn with a series of brisk pats to his cheeks as we all waited quietly for Adi to recover. Then Adi startled awake and began to talk about the American film The Ghost Goes West, a film with the kind of light humor he loves.

I wrote Mother about these conversations but never about the paralyzed silences. She wasn’t interested in Blondi as she knows only border collies with herding behavior that make friends with hills and cliffs not people.

I myself long for my Scotties who are at ease around water and love to swim and wait patiently for me.

“What about the war?” Mother writes. “I have a grandchild to think about. There’s been so much bombing here. How much more can we take? Loudspeakers on street corners tell us to leave. But how? Trains are full of soldiers and impossible to board. My neighbor, Dortchen, remember her? She had to break her son’s arm so he could go to the hospital and get some food. I heard on a British broadcast about the trauma of war on English children. What about our children? And can you ask the Führer about my cook, Thilde? She was sent to a camp two weeks ago. I heard there’s one 9 miles from me. We need such camps to rid ourselves of Communist subversion, and she’s probably close to Dachau that’s beautiful. But I’m at a loss for managing meals by myself. Bakers are prohibited from selling fresh bread because it won’t last as families are tempted to gobble it up. Therefore we get hard day-old rye. But Thilde can always find a baker who is willing to throw in a fresh slice or two.

“Thilde is only a Hausjude, a simple house Jew who never wears a fur collar or hat and who in no way resembles Moses and is so good at finding food. I could understand her being rounded up if she were like all the others with a Biblical profile and being what Himmler calls bacteria. I’m quite aware that she’s not entered in the Nazi Sippenbuch racial book as we are. I tried to get her to go to the anthropological institute for a consultation. I think it’s idiotic she’s Jewish with a skull that looks almost Aryan. And because she’s helped your family so much, couldn’t the Führer make her an honorary gentile? Oh, why did she have to be a Jew?”

When I asked Adi about Thilde, he grew impatient. He hears it all the time from his staff. Somebody has a Jewish barber who is not like a real Jew and should be overlooked. A concert violinist is so talented he couldn’t possibly be held to the same beast-like standards as the rest of them. A professor should be saved as he in no way acts like a Jew and has helped preserve German history. Now this Thilde who doesn’t cook like a Jew and prepares food like a good gentile and is needed to feed a Munich family. All selfish requests. Give in to one, Adi says, and others follow. Where does that leave the purity of the race? “We must sweep with an iron broom.”

“But Adi, you didn’t confine Dr. Bloch to a resettlement camp. You let him leave Germany. Because he treated your mother.”

“Of course.”

But… in Mein Kampf, you advocated no special treatment for any Jew.”

“Mein Kampf is a book, a polemic, an important one, of course, and essential to every soldier and citizen alike. I’m the only one who can sometimes deviate from it for responsible choices.”

“Then can you deviate for our cook, Thilde?”

“Impossible.”

“But why?”

“I decide who is a Jew.”

“But poor Thilde has an ulcer,” I inform Adi. “Mother says she talks of her ulcer as if it were another person: It is hungry. It needs hot soup. It wants some tea. Poor Thilde is in constant battle with her ulcer.”

“Ulcers are the Jewish disease,” he replies.

I know Adi hates diseases and has done everything possible to encourage good health. When he came to power, he urged regular exams and the eating of vegetables. Smokers were asked to quit, and he banned smoking in many public places. It was our friend Dr. Fritz Lickint who found evidence between cigarettes, ulcers and cancer, a fact that is encouraging me to quit. I’m down to eight cigarettes a week because our body belongs to the Führer… especially mine.

Adi was so strict about perfect health that before the war a man could not join the SS who even had a tooth filled.

Find another cook, I tell Mother. Thilde can’t be returned. Adi spends most of his time with maps and charts. What more can I tell Mother? But she only writes to me in desperation: “Sometimes I think anti-Semitism is nothing more than just a way to eliminate our servants.”

12

WITH GENERAL EPAULETTES on his immaculate pearl-gray uniform and booted up to the knees, Keitel limps from the map room and stops by the dining area for a canteen of schnapps. His limp, he claims, is from battle maneuvers, but often he forgets it and steps briskly. Goebbels says Keitel is as listless and weary as Goethe’s second Faust.

Some time after we invaded Russia, General Keitel, his white hair neatly parted, arrived at the Berghof to brief Adi. He found me on the terrace having tea. Unable to control his anger, he raged: “I tell you, Fräulein, my biggest problem in this war is dealing with the intolerable Corporal Götz Rupp.”

Adi insists that a corporal be present at meetings with his generals. It’s his safeguard against what he considers the awful “theory” of war. That’s why he chose Götz Rupp. Little Götz, only 5 feet 4 inches tall, has two lower teeth missing from Operation Gelb where he helped push the Allies back between Calais and Ostend. But even more important, he has a low narrow chin and cheekbones like a whippet and occasionally wears the uniform of the Kaiser’s War in honor of the Führer. Götz was “anointed” after Adi saw him sitting in the Die Neue Welt Bierhalle before a glass of tea when everybody else was drinking hot egg beer and walnut schnapps. A corporal who only drinks tea—though he did eat meat—was the ideal candidate. Meat was deleted soon enough when Bormann enrolled Götz in the snobbish Union Club in Berlin, and Adi ordered the chef to serve the little corporal asparagus, semolina noodles with eggs, and warm pears. So Götz Rupp continues to sit among the rich and the aristocratic who all own racing stables. Everyone assumed he was a guest of Göring who is amused by the weird and uneducated. But Götz, to Adi’s delight, was heard to say loudly over his plum soup: “Today, only grocers are impressed with vons.” Since Götz Rupp was given status that supersedes generals, even the vons of the diplomatic corps never dare to disagree with him. Fancy aristocrats in Mainz who don’t use their titles believing them to be an affectation defer to Götz. For a reward, Adi ordered two racing horses for Götz Rupp—horses housed and fed by the SS that Götz never rode and has never seen.

Adapting to the rich lifestyle, Götz is a proud example of the new worthy bourgeoisie created by the Third Reich from the devastation of a republic.

Magda considers Götz Rupp a eunuch. That’s the way he’s treated by the staff and by the secretaries here in the Bunker. We women talk about our monthlies in front of him, pluck our eyebrows while he sits stiffly by Adi’s door on a duffle bag waiting to be called. But Adi treats Götz with uniform courtesy and quotes him in great detail. Corporal Götz Rupp has no firm party ties and can act as a bridge between Adi and the common soldier. Götz’s wife once worked at the Blohm and Voss shipyard in Hamburg building U-boats that she and her coworkers completed ahead of schedule. This adds to Adi’s admiration of Götz.

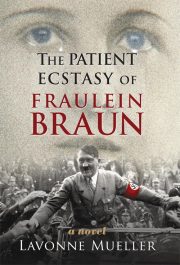

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.