“Germans do not like to die in bed,” the General declared.

“Look at that,” Bickisch added in excitement, “a hollow cavity wound… the brains swept right out of the head. I’ve only read about that.”

“Enough! Not in front of the women,” Krebs ordered.

“Does the front of our car get in the war first?” Helga trilled.

“What do you mean, darling?” Magda asked patiently.

“If the Russians are in front of us… and none are in the back.”

“It doesn’t work that way,” said Bickisch.

“Why not?”

“The First World War had a long, straight front. If we drove—at that time—the front seat would certainly have reached the war first.”

The general smiled, pleased that the child was receiving a first hand history lesson while under his supervision.

“And now?” Helga leaned forward.

“Modern war is elastic. It can reach up, down, forward, backward.”

“War is so silly.” Helga held a frown in a monotonous frozen way like a face held forever on some lacquered vase.

Civilians were digging trenches in yards and parks. Adi’s beloved Reich Chancellery had only two walls standing after a hollow charge had exploded on the roof. “A hollow charge,” Krebs explained without emotion, “is an explosive that burns through steel and concrete.”

People lay dead on the ground, face to face, some with gas bubble wounds bursting from pus. Slogan Squads had painted walls with: “We Will Never Give up” in bright white paint. The fancy jingles of Magda’s pompous husband had not helped Berlin. Barricades and trenches were of little defense. Helga looked at everything, but her mother often shielded her own eyes with a scarf. I was fascinated with the little wooden swastikas people planted everywhere on various piles of rubble, swastikas crudely made from pieces of scarred and jagged wood. Some had a cross attached. How beautiful that surviving family members had risked their lives to walk in all this chaos to honor and bury loved ones the only way they knew how. General Krebs was not impressed as idiot civilians and all their stupid practices were hindering important military operations needed for the war.

Our car moved slowly through smoke, the tires smeared with the paste of human remains. From the car’s half opened window, the smell of gasoline, mud and scorched iron blew into our faces as we drove by a bombed home for blind soldiers and allotment gardens filled with glass shards. Chimneys with no roofs spiked upward like steeples. What Krebs called bomb tramps, Bombenfrischler, were living in the open and cluttering our way.

Loaded with bottles, a milk truck’s tire exploded and the vehicle spun around crashing on a pile of roof tiles. In that brief stop it was being looted by two old men and some children. This fight for milk filled me with hope for if civilians were willing to struggle for milk, men and children alike, then we Germans were not defeated.

Staring at her own intestines on the ground, a girl tried to push them back into her gaping stomach. Stuck to a collapsed wall was the lower half of a horse, so many pieces of animal flesh in a torrid design. Surrounded by newspaper covered corpses, old men and women stood dazed and stiff as if planted in the ground. A boy looking no older than ten was shot by a sniper, and I heard the bullets make a harsh metallic sound and then thunk into his chest as dust flew off his shirt.

“Mothers and children should not leave Berlin. Soldiers fight harder to keep their women safe—though there’s been an increase in premature births,” General Krebs remarked as a tank slowly crawled over the hiding place of a woman and her infant. A body hung from the tank’s turret, charred white from phosphorus shells.

Smoke cleared in one area and in the middle of the street we saw a large player-piano with a woman covered in lime plaster sitting before it and watching the keys go briskly and automatically up and down as she brayed: “Hörst du mein heimliches Rufen. Oh, will you listen to my hidden cry? Please listen.” It was a wine song, I was sure of that. Beer songs are rowdy. This one was soft and dreamy wine. “Will you listen to my hidden cry?” But we didn’t stay to hear the song’s end and drove around the piano and on to a street where Sturmgrenadiers shouted and cheered while they force-marched a line of captured Russians. A captain was filming the Russian prisoners, and Krebs stopped the car abruptly and grabbed the camera from him shouting: “For the Führer!”

“Are we going on Uncle Führer’s autobahn?” Helga asked as her mother wiped a stringy gout of gray puke from around her mouth.

“No dear. We can’t go that way.” I sat half-turned in my seat so I could talk to Magda as she shifted her ample hips even closer to Oberleutnant Bickisch who was elaborating on his days at the Army Artillery School in Juterbog in order to let her know he was well prepared and that she was adequately protected.

“Is this over dressed pipsqueak in the back seat with us a private?” Helga wanted to know.

“He did come late to the Party and is a mere September Recruit. But I assure you, General Krebs would never assign a private to any Nazikinder.”

“I’ve told you, Mutter, over and over, I’m not a child. I’m a Nazi woman.”

“Yes, dear. And Herr Bickisch is a lieutenant.”

“If he’s not a private, why does he have short stubby fingers like all the rest of them?“

“I wouldn’t know, sweetheart.” Magda looked wistfully at the Oberleutnant who flexed his short thick shafts.

Trying to cheer us up, the general spoke of Errol Flynn, how the American actor wrote wonderful pro-Hitler letters and hung out with our good Nazi friend, Herman Erben. Flynn once sported his German uniform in New York City’s Time Square.

I reminded the general that Flynn was also in anti-Nazi films like Dive Bomber.

“That’s how he stays in our support without being silenced,” Krebs answered.

A shell whammed the turret hatch of a German tank just in front of us, and the lumbering vehicle slid across a sidewalk on its side and burst apart—no soldiers climbed out. Greatly fearing for her daughter, Magda threw Helga to the floor shielding her child’s body with her own, but Helga was indignant and bounded up again. We swerved around a dead flame-thrower, and I couldn’t tell by his mangled body if he was German or Russian. Since there was no formal front, we could run into the enemy anywhere. I had heard all the stories of war, how thousands died at one time across a static front. But the war I was seeing and experiencing was a personal one. Shrapnel sprayed all around me, and I was in the open. One could be the target of anyone here. Was it possible that I was right this moment in the sights of a brutish Ivan who wished to rape me off the face of the earth with his scheming bullet? The luck of lust is like the luck of war.

“I don’t see any Russians, but I can smell them,” Helga said.

“What do you smell, dear?”

“Horse poop.”

“We have horses,” I told her.

“Not Commie ones.”

As we tussled and turned in the streets, Helga bounced upon her mother’s lap as if she were riding a bucking horse.

Occasionally women waved their scarves at us. There was shatter tape on many windows, some defiantly and creatively worked into swastikas. Soldiers tried to put smoke pots around to smog the city.

Sniping picked up, and we all had to jump out and take cover under a partially collapsed porch. We were alarmed to find an unexploded bomb lodged in the railing. But the general instantly saw that the bomb’s casing had cracked open and was packed with cardboard. A good German in America—now our savior—had done a masterful job of sabotage.

“Berlin is kaput,” Helga said without emotion as we got back into the car.

No one contradicted Helga. Was it wise to attempt our pistol practice in the city? But weren’t we safe with General Krebs, a most experienced officer?

We passed the Die Neue Welt Bierhalle with its mother-of-pearl coated windows that stood untouched beside the ruins. Its beautiful black hostess had once been the talk of Berlin. Now her club’s interior was nothing but a standing wall scorched and burning. At the corner of Weimarer, we arrived at the popular nightclub Groschenkeller. Many nightclubs were ordered closed for the war, but this one was still open because it also served as a shelter. Air-raid sirens suddenly screamed and then high pitched wailing turned into quick short sinister blasts. General Krebs made us all jump out of the car and run at a crouch to the shelter where men dressed as women hovered in fright, forbidden to enter. Unlucky-looking people are excluded as they give off an air of death.

Entering the shelter, we found drunken soldiers wearing the blue uniform of the Luftwaffe Field Division. I could see a garter tattoo on the arm of a blowzy woman holding up a lantern. Everybody was shouting and screaming and crowding against the wall in the dim light of candles and kerosene lamps. Thick wooden beams lined the ceiling.

“I hope there are no vermin in here,” Helga said primly. She feared insects as much as she feared rats.

“These scrappy people you see are the only vermin in this shelter,” Bickisch replied.

Getting a direct hit, the shelter shook violently.

“Don’t be afraid, little girl,” Oberleutnant Bickisch told Helga, “these walls are very thick.”

“But does God understand concrete?” Helga asked.

“More important, Helga, your Uncle Führer does,” I stated firmly.

“Just take deep breaths when you hear a bomb. That keeps your lungs from shattering,” Bickisch offered.

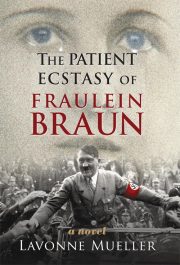

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.