“I’ve heard that story a hundred times.” Magda studies her palms in boredom, flexing her finger over and over, an exercise she believes will give her slender hands.

“He more than satisfies me,” I say.

“Oh, tell that to Blondi.” Her voice suddenly blares like a bus entering a tunnel.

“He does. Really, Magda.”

I don’t think Magda ever got too close to Adi. I do know she wants that more than anything. And maybe she has to play games with me like believing I can’t fulfill Adi as she could, pleasuring herself one way or the other even if it’s second hand. How can I blame her? I’m the one who has a poem that Adi wrote in small vertical old German script that he gave me after our second year together.

“I suspect his is beautiful,” Magda says begrudgingly.

“Why should it be beautiful?” I snap. “He’s the Führer. Isn’t that enough?”

“I know he has three testicles.” Magda stands defiantly, legs apart and hands behind her back, like one of her stubborn children.

“How do you know that?”

“Hess.” Magda says his name as if it were the ultimate source.

“Is that why Hess flew off landing in an enemy field? He wanted to make a peace deal with the British behind our backs because of one extra testicle? Our Führer is full of extras.”

“I never liked Hess, Eva. Right from the beginning. Even when he was the Führer’s respected deputy.”

“Tell that to Blondi.”

“Pfui, pfui. The Führer is always too trusting. You know that, Eva, trusting and… wonderful. Sometimes, when the Führer’s talking to us, when his passionate words are rolling from his jaws, sometimes…”

“What? Sometimes what?”

“His rear quivers. It makes you realize that somewhere in Europe there are psychics who can tell the future by one’s bottom.”

“Magda, I find that very offensive.”

“The marvelous slight ripples underneath his trousers…”

“You shouldn’t take notice of things like that.”

“Evie, for proof that we’re going to win, look at the rumps of our soldiers. They have rears more robust than before the war.”

“But Adi’s is mine alone. You can have the others.” I give an aggrieving sneer.

Adi used to lounge on the floor, his arms around his knees. With this great man sitting on the ground, I felt awkward resting on a comfortable chair. But his heart is always on the battlefield, down on the earth—close to the trenches. When he became the Führer, he leaned against his desk, and I envied the sharp wooden edges sinking into his skin. I’d look up his nose straight to his nostrils, unlike any other nostrils, for there were little dark hunks of tillage and clotted soil that he had coveted and conquered even there.

“You must remember, Magda, your Germany is gone. I’m the woman of the house down here. In the Bunker, I’m official.”

“Jawohl. Jawohl. You hope to climax at last.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Everybody knows the Führer can’t be bothered with sauce, even his own Sauce.” Magda pats her dress, the last Chanel that her husband seized when leaving Paris. The bodice is altered so that there’s a reverse cleavage with the ends of her pendulous breasts showing through an opening of silk just above her waist while the neckline reaches up around her ears. It’s a dress she continues to wear as a statement. Part of Paris still belongs to Germany.

9

AS THE IVANS GET CLOSER AND CLOSER, General Krebs decided that Magda and I go topside to do pistol practice. He feels every German man or woman is honor bound to take a random shot at the enemy, even me, as well as the Reichsminister’s Frau. The Red Army is in our streets, are they not? Americans are not far behind. Our pistol lessons would be a “surprise gift” for the Führer. And one had only to look outside and see ladies walking by with pistol belts over their pinafores for Goebbels decreed shooting instructions for women.

I’m elated for I yearn to go outside. Even though I love my home here below, now that I’m official, I want to ride in full view in the streets of Berlin. The thrill of it. Being seen.

Krebs insisted that Magda’s oldest daughter, Helga, eleven years old, also learn to shoot. At first Magda violently disagreed until General Krebs said his baby sister was shooting at the age of eight. Did the Reichsminister’s Frau want her daughter to be helpless? Maybe raped?

At eleven I had learned to handle a horse and throw a javelin, but I had no experience with a gun.

General Krebs and his orderly would drive to a suitable spot. It was not wise to shoot around the top of the Bunker and call attention to the Führer’s headquarters. Assuring us that Germany’s barricades and street sentries were all in place, he promised to do the driving himself. There are more of us in Berlin than the Russians. We would admit defeat by being afraid to go out in our own city. Furthermore, the general felt women should be prepared for their own safety, and the only way to do that was to be in the true and real arena up above. Finally, Krebs presented us with a large Walther pistol 7.65. To Helga, he gave a smaller Walther 6.35 and tied a little pink bow around her gun. Inside the barrel he stuffed schokoladecreme as Fräulein Manzialy struggles so successfully to save chocolate soufflé and chocolate karamelsauce in abundance for her Führer. Krebs chuckled and whispered to Helga that the Walther’s chambers were full, ready to explode and when she got an Ivan, she would see chocolate splatter on a Russian heart. Was that not a delicious way to end things?

“Won’t Uncle Führer be pleased when he finds we’re soldiers, too.” Magna was trying hard to be festive. “You know he says—everyone to their duty.”

Having experienced her first menstruation, Helga was pleased to be treated as an adult. Dr. Morell donated cotton from the tops of his medicine bottles to reinforce her underwear. When the cotton ran out, he pulled soiled bandages from the wounded that the nurses then washed and folded in little pads for her.

Helga was Adi’s favorite as well as her father’s. Both men wanted every detail about Helga’s first monthly that arrived according to Dr. Morell at a very early age, a natural sign of superiority. This young blood, her German heritage, Blut Träger, came forth in shy little bursts as if she had been pricked between the legs. We had prepared her for this monthly event, so Helga was not frightened. It helped that she was not afflicted with cramps. Adi insisted on inspecting the first bloody pad, so I wrapped it in the pages of my favorite magazine, Illustrierte Beobachter, and put it on his desk. He screamed at me saying the wrapping was contaminating Helga’s blood. Anything that was not Goebbels’ paper, Das Reich, was filthy. Disgusting print had bled on the cotton and distorted his examination. I had never thought of this possibility and was sorry telling Adi I would save him Helga’s second menstrual pad in the Panzerbär, the combat newspaper Goebbels so lovingly edits. But it was the first smear that he wanted. Finally he decided that the original sample was not ruined after all and wrote his name with her scarlet smear saying Nietzsche declared that those who wrote with blood would learn that blood was spirit.

Blondi’s doggy-afterbirth was also saved, carefully dried and pressed in a glass bowl like a paperweight. But it was Adi’s clinical study of Helga’s menstrual blood that impressed Dr. Morell. The doctor watched Adi study the ruby streaks under a microscope. The tiny lumps fascinated Adi, those delicate jagged red knots that came from a child. Extracting clots from the pad carefully with a tweezers, he put them in the palm of his hand tasting the innocent blood as if he were confirming the fact that this was indeed a rare and precious substance. It affected him peculiarly, however, as he began to shiver. Klara had given him dripping blood pudding to eat as a child, and he was hit with a stab of pure and innocent memories—Helga connected with his beloved mother.

After a breakfast of fried duck eggs and horsemeat bacon in the Officers’ Mess at Panzer Division Munchenberg, General Krebs arrived at the Bunker. We tumbled into an armored Mercedes in late afternoon, ready for pistol practice. Krebs thought about having a squad of Hitler Youth to escort us, but he and General Heinrici and Oberleutnant von Roon had made enough early ground reconnaissance to be quite certain of our safety. Krebs was eager to take full credit for the “Führer’s surprise” and insisted his orderly not drive on such an important mission. Helga sat on her mother’s lap in the back seat, mother and child tucked in tightly next to orderly Oberleutnant Bickisch in his hussar’s jacket with frogging and gold epaulets, a bayonet slash across his cheek acquired from his military sports school at Wunstorf. I sat in the front seat next to General Krebs with his large mouth and square teeth, dressed in a simple overcoat with gray tin buttons and no rank insignia, a watch on each wrist, a map case and a Steyr army pistol strapped to his side. The dour general was trying to be casual, but I could see lines of sweat on his forehead. When we drove up a hill, Helga vomited on Bickisch’s shoes. Magda had failed to tell us that Helga got carsick. We snaked around a woman using scissors to hack at a dead horse, then continued driving by burnt tanks, partial buildings, slabs of street pavement, and scattered shoes, many with human feet or legs still in them. Some bodies in the street had boiled cabbage all over them. One dead soldier lay in the road, steam still rising up from the mug of coffee he clutched in his hand.

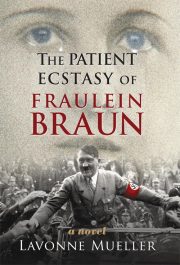

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.