She knows that he has to die. All her advisors say that she must harden her heart and have him executed. He may be her cousin and beloved to her, but he is a known and declared rebel. Alive, he would be a figurehead for every traitor, every day, for the rest of her reign. Forgiven, he would make every spy hope for forgiveness, and how would Cecil rule by terror if we were known to have a merciful queen? Cecil’s England is darkened by apprehension. He cannot have a queen who turns kind. Howard is a challenge to the rule of terror whether he likes it or not. He has to die.

But this is her cousin that she has loved from childhood. We all know and love him. We all have a story about his temper or his wit, about his absurd pride and his wonderful taste. We have all relished his lavish hospitality; we have all admired his great lands, the fidelity of his servants, the devotion that he showed to his wives; this is a man I have been proud to call my friend. We all care for his children, who will be orphans tomorrow, another generation of heartbroken Howards. We all want this man to live. Yet tomorrow I will stand before his scaffold and witness his execution and then go down the river and tell his cousin the queen that he is dead.

I am thinking of all this as I walk along the cold lane around the White Tower, and then I check as two women are coming the other way. In the flicker of the torchlight I see the queen, walking with a lady-in-waiting behind her, a yeoman of the guard behind the two of them, his torch smoking in the cold air from the river.

“You here too?” she says quietly to me.

I take my hat from my head and I kneel on the wet cobbles.

“Sleepless too, old man?” she says with a ghost of a smile.

“Sleepless and sad,” I say.

“I too,” she says with a sigh. “But if I forgive him, I sign my own death warrant.”

I stand up. “Walk with me,” she says and puts her hand in my arm. We go together, slowly, the white stonework of the Tower beside us gleaming in the moonlight. Together we walk up the steps to the open grass of Tower Green, where the scaffold is new-built and smelling of fresh wood, like a stage waiting for players, expectant.

“Pray God it stops here,” she says, looking at the scaffold where her own mother put down her head. “If you can stop her plotting, Shrewsbury, this can be the last man who dies for her.”

I cannot promise. The other queen will go to her grave demanding her freedom, asserting the sanctity of her person. I know this now, as I know her: she is a woman I have loved and studied for years.

“You would never execute her?” I say, very low.

The white face Elizabeth turns to me is that of a gorgon in her cold forbidding beauty, a dangerous angel. The torch behind her gives her a halo of gold like a saint, but the flicker of smoke smells of sulfur. The sight of her, a queen triumphant, ringed with fire, strange and silent, fills me with wordless terror as if she were some kind of portent, a blazing comet, foretelling death.

“She says her person is sacred but it is not sacred,” she says quietly. “Not anymore. She is Bothwell’s whore and my prisoner; she is not a sanctified queen anymore. The common people call her a whore; she has destroyed her own magic. She is my cousin but—see here—tonight she has taught me to kill my own kin. She has forced me to put my own family on the block. She is a woman and a queen as I am, and she herself has shown me that a woman and a queen is not immune from assassins. She herself has shown me how to put a knife to the throat of a queen. I pray that I will not have to execute her. I pray that it stops here, with my cousin, with my beloved cousin. I pray that his death is enough for her. For if I am ever advised to kill her, she herself has shown me the way.”

She sends me away with a small gesture of her hand and I bow and leave her with her lady-in-waiting and the yeoman of the guard with his torch. I go from the darkness of the Tower to the darker streets and walk to my home. Behind me all the way, I hear the quiet footsteps of a spy. Someone is watching me all the time now. I lie down on my bed, fully clothed, not expecting to sleep, and then I doze and have the worst nightmare I have ever suffered in my life. It is a jumble of terrible thoughts, all mistaken, a wicked roil from the devil himself, but a dream so real that it is like a seeing, a foreshadowing of what is to come. I could almost believe myself enchanted. I could believe myself accursed with foresight.

I am standing before the scaffold with the peers of the realm, but it is not Norfolk that they bring before us from an inner room but the queen’s other treacherous cousin: my Mary, my beloved Mary, the Queen of Scots. She is wearing her velvet gown of deepest black and her face is pale. She has a long white veil pinned to her hair and an ivory crucifix in her hand, a rosary around her slim waist. She is in black and white, like a nun in orders. She is as beautiful as the day I saw her first, ringed with fire, at bay, under the walls of Bolton Castle.

As I watch, she puts her top gown aside and hands it to her maid. There is a ripple of comment in the crowded great hall, for her under-gown is scarlet silk, the color of a cardinal’s robe. I would smile if I were not biting my lips to keep them from trembling. She has chosen a gown which slaps the face of this Protestant audience, telling them that she is indeed a scarlet woman. But the wider world, the Papist world, will read the choice of color very differently. Scarlet is the color of martyrdom; she is going to the scaffold dressed as a saint. She is proclaiming herself as a saint who will die for her faith, and we who have judged her, and are here to witness her death, are the enemies of heaven itself. We are doing the work of Satan.

She looks across the hall at me and I see a moment of recognition. Her eyes warm at the sight of me and I know my love for her—which I have denied for years—is naked on my face for her to see. She is the only one who will truly know what it costs me to stand here, to be her judge, to be her executioner. I start to raise my hand, but I check myself. I am here to represent the Queen of England; I am Queen Elizabeth’s Lord High Steward, not Mary’s lover. The time when I could reach out for the queen that I love has long gone. I should never even have dreamed that I might reach out for her.

Her lips part, I think she is about to speak to me, and despite myself I lean forward to hear. I even take a step forward, which takes me out of the line of the peers. The Earl of Kent is beside me, but I cannot stand with him if she wants to say something to me. If this queen calls my name as she says it, as only she says it, “Chowsbewwy!” then I will have to go to her side, whatever it costs me. If she stretches out for me I will hold her hand. I will hold her hand even as she puts her head on the block if she wishes. I cannot refuse her now. I will not refuse her now. I have spent my life serving one queen and loving the other. I have broken my heart between the two of them, but now, at this moment, at the moment of her death, I am her man. If Queen Mary wants me at her side, she shall have me. I am hers. I am hers. I am hers.

Then she turns her head and I know that she cannot speak to me. I cannot listen for her. I have lost her to heaven, I have lost her to history. She is a queen through and through; she will not spoil this, her greatest moment, with any hint of scandal. She is playing her part here in her beheading as she played her part in her two great coronations. She has gestures to make and words to say. She will never speak to me again.

I should have thought of this when I went to her chamber to tell her that her sentence had come, that she was to die the next day. I did not realize it. So I did not say goodbye to her then. Now I have lost my chance. Lost it forever. I may not say goodbye to her. Or only in a whisper.

She turns her head and says a word to the dean. He starts the prayers in English and I see that characteristic irritable shrug of the shoulders and the petulant turn of the head that means that she has not had her own way, that someone has refused her something. Her impatience, her wilfulness, even here on the scaffold, fill me with delight in her. Even at the very doorway of death she is irritated at not getting her own way. She demands that her will is done as a queen, and God knows it has been my joy to serve her, to serve her for years—many, many years, for sixteen years she has been my prisoner, and my beloved.

She turns to the block and she kneels before it. Her maid steps forward and binds her eyes with a white scarf. I feel a sharp pain in my palms and I find I am clenching my fists and driving my fingernails into my own flesh. I cannot bear this. I must have seen a dozen executions in my time but never a queen, never the woman I love. Never this. I can hear a low groan like an animal in pain and I realize it is my voice. I clench my teeth and say nothing while she finishes her prayer and puts her head gently down, her blanched cheek against the wood.

The headsman lifts his axe and at that moment…I wake. The tears are wet on my cheeks. I have been crying in my sleep. I have been crying like a child for her. I touch my pillow and it is damp with my tears and I feel ashamed. I am unmanned by the reality of Howard’s execution, and my fears for the Scots queen. I must be very tired and very overwhelmed at what we are going to do today that I should cry like a child in my sleep.

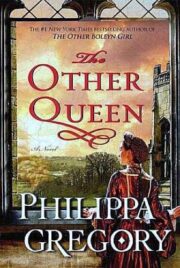

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.