1572, JANUARY,

SHEFFIELD CASTLE:

MARY

The little candle flame bobs at my window, and at midnight, when I bend down to blow it out, I hesitate as I see an answering wink from a quickly doused lantern, down in the shadows of the garden where the dark trees overhang the dark grass. There is a small new moon, hidden by scudding clouds, throwing no light on the stone wall below me. It is black as a cliff.

I did this three years ago at Bolton Castle when I trusted in my luck; I thought no walls could keep me in; I thought some man would be bound to rescue me. Elizabeth would not be able to resist my persuasion, or my family would rise up for me, Bothwell would come for me. I could not believe that I would not once again be at a beautiful court, beloved, enchanting, at the heart of everything.

Now it is not the same. I am not the same. I am weary from three years in prison. I am heavier, I have lost my wiry strength, I am no longer tireless, undefeated. When I climbed down the wall at Bolton Castle I had spent a week on the run from my enemies; I was hardened. Here, in the three years of luxurious imprisonment, I have been overfed and bored, inflamed with false hopes and distracted by my own dreams, and I am never well.

I am a different woman in my heart. I have seen the North rise and fall for me, I have seen my men swinging as picked-off bones on the gibbets at the village crossroads. I have accepted a man in marriage and learned of his arrest. And I have waited and waited for Bothwell, certain that he would come to me. He does not come. He cannot come. I have realized that he will never come to me again, even if I order him not to. Even if I send to tell him I never want to see him again, even though he would understand the prohibition is an invitation, he cannot come.

Courage! I bend my head and blow out the little flame. I have nothing to lose by trying, and everything to gain. As soon as I am free again I shall have everything restored to me, my health, my beauty, my fortune, my optimism, Bothwell himself. I check that the sheets are knotted around my waist, I hand the end to John my steward, I smile at Mary Seton and give her my hand to kiss. I will not wait for her, this time; I will not take a maid. I shall start running the moment that my feet touch the ground.

“I will send for you when I am in France,” I say to her.

Her face is pale and strained, tears in her eyes. “God speed,” she says.“Bonne chance!”

She swings open the lattice window and John winds the rope of sheets around the strong wooden post of the bed, and braces himself to take my weight.

I nod my thanks to him and step up to the windowsill, bend my head to get out of the window, and at that very moment there is a hammering on my door and Ralph Sadler’s gruff voice hollering, “Open up! In the name of the queen! Open up!”

“Go!” John urges me. “I have you! Jump.”

I look down. Below me at the foot of the wall I see a gleam of metal; there are soldiers waiting. Hurrying from the main house come a dozen men with torches.

“Open up!”

I meet Mary Seton’s appalled gaze and I shrug. I try to smile, but I feel my lip tremble.“Mon dieu,” I say. “What a noise! Not tonight, then.”

“Open in the name of the queen, or I will break down this door!” Sadler bellows like a bull.

I nod to John. “I think you had better let him in,” I say.

I put out my hand to Mary and let her help me down from the window. “Quickly,” I say. “Untie the rope. I don’t want him to see me like this.”

She fumbles as he hammers with the hilt of his sword. John throws open the door and Sadler falls inwards. Behind him is Bess, white-faced, her hand tugging at his sleeve, holding back his sword arm.

“You damned traitor, you damned treasonous, wicked traitor!” he hollers as he stumbles into the room and sees the knotted sheets on the floor and the open window. “She should take your head off; she should take your head off without trial.”

I stand like a queen and say nothing.

“Sir Ralph…,” Bess protests. “This is a queen.”

“I could damned well kill you myself!” he shouts. “If I threw you out of the window now I could say that the rope broke and you fell.”

“Do it,” I spit.

He bellows in his rage and Mary dives between us and John moves closer, fearing this brute will lunge at me in his temper. But it is Bess who prevents him, tightening her grip on his arm. “Sir Ralph,” she says quietly, “you cannot. Everyone would know. The queen would have you tried for murder.”

“The queen would thank God for me!” he snaps.

She shakes her head. “She would not. She would never forgive you. She does not want her cousin dead; she has spent three years trying to find a way to restore her to her throne.”

“And look at the thanks she gets! Look at the love which is returned her!”

“Even so,” she says steadily, “she does not want her death.”

“I would give it her as a gift.”

“She does not want her death on her conscience,” Bess says, more precisely. “She could not bear it. She does not wish it. She will never order it. A queen’s life is sacred.”

I feel icy inside. I don’t even admire Bess for defending me. I know she is defending her own house and her own reputation. She doesn’t want to go down in history as the hostess who killed a royal guest. Mary Seton slips her hand in mine.

“You will not touch her,” she says quietly to Sir Ralph. “You will have to kill me, you will have to kill us all first.”

“You are blessed in the loyalty of your friends,” Sir Ralph says bitterly. “Though you yourself are so disloyal.”

I say nothing.

“A traitor,” he says.

For the first time I look at him. I see him flush under the contempt of my gaze. “I am a queen,” I say. “I cannot be named as a traitor. There can be no such thing. I am of the blood royal; I cannot be accused of treason; I cannot be legally executed. I am untouchable. And I don’t answer to such as you.”

A vein throbs in his temple; his eyes goggle like those of a landed fish. “Her Majesty is a saint to endure you in her lands,” he growls.

“Her Majesty is a criminal to hold me against my consent,” I say. “Leave my room.”

His eyes narrow. I do believe he would kill me if he could. But he cannot. I am untouchable. Bess tugs gently at his arm and together they leave. I could almost laugh: they go backwards, step by stiff step, as they must do when they leave a royal presence. Sadler may hate me, but he cannot free himself from deference.

The door closes behind them. We are left alone with our candle still showing a wisp of smoke, the open window, and the knotted rope dangling in space.

Mary pulls in the rope, snuffs the candle, and closes the window. She looks out over the garden. “I hope Sir Henry got away,” she says. “God help him.”

I shrug. If Sir Ralph knew where to come and at what time, the whole plot was probably penetrated by Cecil from the moment that Sir Henry Percy first hired his horses. No doubt he is under arrest now. No doubt he will be dead within the week.

“What shall we do?” Mary demands. “What shall we do now?”

I take a breath. “We go on planning,” I say. “It is a game, a deadly game, and Elizabeth is a fool for she has left me with nothing to do but to play this game. She will plot to keep me, and I will plot to be free. And we shall see, at the very end, which of us wins and which of us dies.”

1572, MARCH,

CHATSWORTH:

BESS

Iam bidden to meet my lord, his lawyer, and his steward in his privy chamber, a formal meeting. His lawyer and clerks have come from London, and I have my chief steward to advise me. I pretend to ignorance, but I know what this is all about. I have been waiting for this all the weeks after the verdict of guilty on Howard and my lord’s silent return home.

My lord has served his queen as loyally as any man could do but even after the verdict she wanted, she has not rewarded him. He may be Lord High Steward of England but he is a great lord only in reputation. In reality he is a pauper. He has no money left at all, and not a field that is not mortgaged. He has returned from London as a man broken by his own times. Howard is sentenced to death and it will be Cecil’s England now, and my lord cannot live in peace and prosperity in Cecil’s England.

Under the terms of our marriage contract my lord has to give me great sums of money at my son’s coming of age. Henry is now twenty-one years old and Charles will soon be twenty, and my lord will owe me their inheritance and the money for my other children on the first day of April, as well as other obligations to me. I know he cannot pay it. He cannot get anywhere near to paying it.

In addition to this I have been lending him money to pay for the queen’s keep for the past year, and I have known for the past six months that he won’t be able to repay me this either. The expense of housing and guarding the Queen of Scots has cost him all the rents and revenues of his land, and there is never enough money coming in. To settle his debt to me, to fulfil his marriage contract, he will have to sell land or offer me land instead of the money he should pay me.

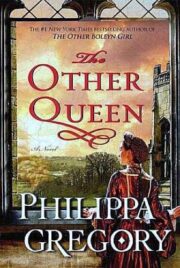

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.