“She will give up her building projects while she is caring for the queen,” I tell him. “Anyway, I think she must have finished the work on Chatsworth by now. How much work does a house need? It is good enough now, surely? She will have to give up her business interests too; I shall have my stewards take over her work.”

“You’ll never get her to hand over her farms and her mines, and she’ll never finish building,” he predicts. “She is a great artificer, your new wife. She likes to build things, she likes property and trade. She is a rare woman, a venturer in her heart. She will build a chain of houses across the country, and run your estates like a kingdom, and launch a fleet of ships for you, and found a dynasty of your children. Bess will only be satisfied when they are all dukes. She is a woman whose only sense of safety is property.”

I never like it when Cecil talks like this. His own rise from clerk to lord has been so sudden, on the coattails of the queen, that he likes to think that everyone has made their fortunes from the fall of the church, and that every house is built with the stone of abbeys. He praises Bess and her mind for business, only to excuse himself. He admires her profits because he wants to think that such gains are admirable. But he forgets that some of us come from a great family that was rich long before the church lands were grabbed by greedy new men, and some of us have titles that go back generations. Some of us came over as Norman noblemen in 1066. This means something, if only for some of us. Some of us are wealthy enough, without stealing from priests.

But it is hard to say any of this without sounding pompous. “My wife does nothing that does not befit her position,” I say, and Cecil gives a little laugh as if he knows exactly what I am thinking.

“There is nothing about the countess and her abilities that does not befit her position,” he says smoothly. “And her position is very grand indeed. You are the greatest nobleman in England, Talbot, we all know that. And you do right to remind us, should we ever make the mistake of forgetting it. And all of us at court appreciate Bess’s good sense; she has been a favorite amongst us all for many years. I have watched her marry upwards and upwards with great pleasure. We are counting on her to make Tutbury Castle a pleasant home for the Queen of Scots. The countess is the only hostess we could consider. No one else could house the Queen of Scots. Any other house would be too mean. No one but Bess would know how to do it. No one but Bess could triumph.”

This flattery from Cecil should content me, but we seem to be back to Bess again, and Cecil should remember that before I married her she was a woman who had come up from nothing.

1568, WINTER,

BOLTON CASTLE:

MARY

It is to be tonight. I am going to escape from Bolton Castle, their so-called,soi-disant , “impregnable” Yorkshire castle, this very night. Part of me thinks: I dare not do this, but I am more terrified of being trapped in this country and unable to go either forward or back. Elizabeth is like a fat ginger cat on a cushion; she is content to sit and dream. But I must reclaim my throne, and in every day of my exile, the situation grows worse for me. I have castles holding out for me in Scotland and I must get relief to them at once. I have men ready to march under my standard, I cannot make them wait. I cannot let my supporters die for lack of my courage. I have Bothwell’s promise that he will escape from Denmark and return to command my armies. I have written to the King of Denmark, demanding Bothwell’s freedom. He is my husband, the consort of a queen, how dare they hold him on the word of a merchant’s daughter who complains that he promised marriage? It is nonsense, and the complaints of such a woman are of no importance. I have a French army mustering to support me, and promises of Spanish gold to pay them. Most of all, I have a son, a precious heir,mon bйbй ,mon chйri , my only love, and he is in the hands of my enemies. I cannot leave him in their care: he is only two years old! I have to act. I have to rescue him. The thought of him without proper care, not knowing where I am, not understanding that I was forced to leave him, burns me like an ulcer in my heart. I have to get back to him.

Elizabeth may dawdle, but I cannot. On the last day of her nonsensical inquiry I received a message from one of the Northern lords, Lord Westmorland, who promises me his help. He says he can get me out of Bolton Castle, he can get me to the coast. He has a train of horses waiting in Northallerton and a ship waiting off Whitby. He tells me that when I say the word he can get me to France—and as soon as I am safe at home, in the country of my late husband’s family, where I was raised to be queen, then my fortunes will change in an instant.

I don’t delay, as Elizabeth would delay. I don’t drag my feet and puzzle away and put myself to bed, pretending illness as she does whenever she is afraid. I see a chance when it comes to me and I take it like a woman of courage. “Yes,” I say to my rescuer. “Oui,”I say to the gods of fortune, to life itself.

And when he says to me, “When?” I say, “Tonight.”

I don’t fear, I am frightened of nothing. I escaped from my own palace at Holyrood when I was held by murderers; I escaped from Linlithgow Castle. They will see that they can take me but they cannot hold me. Bothwell himself said that to me once, he said, “A man can take you, but you cling to your belief that he can never own you.” And I replied, “I am always queen. No man can command me.”

The walls of Bolton Castle are rough-hewn gray stone, a place built to resist cannon, but I have a rope around my waist and thick gloves to protect my hands and stout boots so that I can kick myself away. The window is narrow, little more than a slit in the stone, but I am slim and lithe, and I can wriggle out and sit with my back to the very edge of the precipice, looking down. The porter takes the rope and hands it to Agnes Livingstone and watches her as she ties it around my waist. He makes a gesture to tell her to check that it is tight. He cannot touch me, my body is sacred, so she has to do everything under his instruction. I am watching his face. He is not an adherent of mine, but he has been paid well, and he looks determined to do his part in this. I think I can trust him. I give him a little smile and he sees my lip tremble with fear, for he says, in his rough northern accent, “Dinnae fret, pet.” And I smile as if I understand him and watch him wind the rope around his waist. He braces himself and I wriggle to the very brink and look down.

Dear God, I cannot see the ground. Below me is darkness and the howl of air. I cling to the post of the window as if I cannot let it go. Agnes is white with fear, the porter’s face steady. If I am going to go, I have to go now. I release the comfort of the stone arch of the window, I let myself stretch out onto the rope. I step out into air. I feel the rope go taut and terrifyingly thin, and I start to walk backwards, into the darkness, into nothingness, my feet pushing against the great stones of the walls, my skirt filling and flapping in the wind.

At first, I feel nothing but terror, but my confidence grows as I take step after step and feel the porter letting out the rope. I look up and see how far I have come down, though I don’t dare to look below. I think I am going to make it. I can feel the joy at being free growing inside me until my very feet tremble against the wall. I feel sheer joy at the breath of the wind on my face, and even joy at the vast space beneath me as I go down: joy at being outside the castle when they think I am captive, cooped up in my stuffy rooms, joy at being in charge of my own life again, even though I am dangling at the end of a rope like a hooked trout, joy at being me—a woman in charge of her own life—once more.

The ground comes up underneath me in a dark hidden rush and I stagger to my feet, untie the rope, and give it three hard tugs and they pull it back up. Beside me is my page, and Mary Seton, my lifelong companion. My maid-in-waiting will come down next; my second lady-in-waiting, Agnes Livingstone, after her.

The sentries at the main gate are careless: I can see them against the pale road, but they cannot see us against the dark of the castle walls. In a moment there is to be a diversion—a barn is to be fired, and when they hurry to put out the fire, we will run down to the gate where horses will come galloping up the road, each rider leading a spare, the fastest for me, and we will be up and away, before they have even realized we are gone.

I stand quite still, not fidgeting. I am excited and I feel strong and filled with the desire to run. I feel as if I could sprint to Northallerton, even to the sea at Whitby. I can feel my power flowing through me, my strong young desire for life, speeding faster for fear and excitement. It beats in my heart and it tingles in my fingers. Dear God, I have to be free. I am a woman who has to be free. I would rather die than not be free. It is true: I would rather die than not be free.

I can hear the soft scuffle as Ruth, my maid, climbs out of the window and then the rustle of her skirts as the porter starts to lower her. I can see the dark outline of her quietly coming down the castle wall, then suddenly the rope jerks and she gives a little whimper of fear.

“Sshh! Sssh!” I hiss up at her, but she is sixty feet above me, she cannot hear. Mary’s cold hand slips into mine. Ruth isn’t moving, the porter is not letting her down, something has gone terribly wrong, then she falls like a bag of dusters, the rope snaking down from above her as he drops it, and we hear her terrified scream.

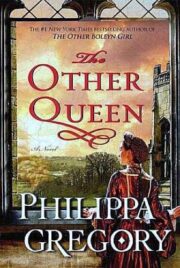

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.