“But you must eat!” Bess presses him.

“No, I must go. My lord expects me back at once. I was only to ascertain what you have kindly told me, take the relevant men into custody, and bring them back to London. I do thank you for your hospitality.” He bows to Bess, he bows to me, he turns on his heel, and he has gone. We hear his riding boots clatter away down the stone steps before we realize that we are safe. We never even got as far as the gallery; this interrogation all took place on the stairs. It started and was completed in a moment.

Bess and I look at each other as if a storm has blown through our garden destroying every blossom, and we don’t know what to say.

“Well,” she says with pretended ease, “that’s all right then.”

She turns to leave me, to go back to her business, as if nothing has happened, as if she was not meeting with plotters in my house, conspiring with my own servants, and surviving an interrogation from Cecil’s agents.

“Bess!” I call her. It comes out too loudly and too harshly.

She stops and turns to me at once. “My lord?”

“Bess, tell me. Tell me the truth.”

Her face is as yielding as stone.

“Is it how you said, or did you think that the plot might go ahead? Did you think that the queen might be tempted to consent to the escape, and you would have sent her out with these men into certain danger and perhaps death? Though you knew she has only to wait here to be restored to her throne and to happiness? Bess, did you think to entrap her and destroy her in these last days while she is in your power?”

She looks at me as if she does not love me at all, as if she never has done. “Now why would I seek her ruin?” she asks coldly. “Why would I seek her death? What harm has she ever done me? How has she ever robbed me?”

“Nothing. I swear, she has not harmed you; she has taken nothing from you.”

Bess gives a disbelieving laugh.

“I am faithful to you!” I exclaim.

Her eyes are like arrow slits in the stone wall of her face. “You and she, together, have ruined me,” she says bitterly. “She has stolen my reputation as a good wife; everyone knows that you prefer her to me. Everyone thinks the less of me for not keeping your love. I am shamed by your folly. And you have stolen my money to spend on her. The two of you will be my ruin. She has taken your heart from me and she has made me see you with new, less loving eyes. When she came to us, I was a happy, wealthy wife. Now I am a heartbroken pauper.”

“You shall not blame her! I cannot let the blame fall on her. She is innocent of everything you say. She shall not be falsely accused by you. You shall not lay it at her door. It is not her doing—”

“No,” she says. “It is yours. It is all yours.”

1570, AUGUST,

WINGFIELD MANOR:

MARY

My darling Norfolk, for we are still betrothed to marry, copies to me the playscript of the charade he must act. He has to make a complete submission to his cousin the queen, beg her pardon, assure her that he was entrapped into a betrothal with me under duress and as a fault of his own vanity. The copy that he sends me of his submission, for my approval, is so weepingly guilty, such a bathetic confession of a man unmanned, that I write in the margin that I cannot believe even Elizabeth will swallow it. But, as so often, I misjudge her vanity. She so longs to hear that he never loved me, that he is hers, all hers, that they are all of them, all her men, all of them in love with her, all of them besotted with her poor old painted face, her bewigged head, her wrinkled body, she will believe almost anything—even this mummery.

His groveling makes its own magic. She releases him, not to return to his great house in Norfolk, where they tell me that his tenants would rise up for him in a moment, but to his London palace. He writes to me that he loves this house, that he will improve and embellish it. He will build a new terrace and a tennis court, and I shall walk with him in the gardens when we pay our state visits as King Consort and Queen of Scotland. I know he thinks also of when we will inherit England. He will improve this great house so that it will be our London palace; we will rule England from it.

He writes to me that Roberto Ridolfi is thankfully spared and is to be found in the best houses in London again, knowing everyone, arranging loans, speaking in whispers of my cause. Ridolfi must have nine lives, like a cat. He crosses borders and carries gold and services plots and always escapes scot-free. He is a lucky man, and I like to have a lucky man in my service. He seems to have strolled through the recent troubles, though everyone else ended up in the Tower or exile. He went into hiding during the arrests of the Northern lords, and now, protected by his importance as a banker and his friendship with half the nobles of England, he is at liberty once more. Norfolk writes to me that he cannot like the man, however clever and eager. He fears Ridolfi is boastful and promises more than he can achieve, and that he is the very last visitor my betrothed wants at Howard House, which is almost certainly watched day and night by Cecil’s men.

I reply that we have to use the instruments that come to hand. John Lesley is faithful but not a man of action, and Ridolfi is the one who will travel the courts of Europe seeking allies and drawing the plots together. He may not be likable—personally, I have never even laid eyes on him—but he writes a persuasive letter and he has been tireless in my cause. He meets with all the greatest men of Christendom and goes from one to another and brings them into play.

Now he brings a new plan from Philip of Spain. If these present negotiations to return me to my throne break down again, then there is to be an uprising by all the English lords—not just those of the North. Ridolfi calculates that more than thirty peers are secret Papists—and who should know better than he who has the ear of the Pope? The Pope must have told him how many of Elizabeth’s court are secretly loyal to the old faith. Her situation is worse than I realized if more than thirty of her lords have secret priests hiding in their houses and take Mass! Ridolfi says they only need the word to rise, and King Philip has promised to provide an army and the money to pay them. We could take England within days. This is “the Great Enterprise of England” remade afresh, and though my betrothed does not like the man, he cannot help but be tempted by the plan.

“The Great Enterprise of England,” it makes me want to dance, just to hear it. What could be greater as an enterprise? What could be a more likely target than England? With the Pope and Philip of Spain, with the lords already on my side, we cannot fail. “The Great Enterprise,” “the Great Enterprise,” it has a ring to it which will peal down the centuries. In years to come men will know that it was this that set them free from the heresy of Lutheranism and the rule of a bastard usurper.

But we must move quickly. The same letter from Norfolk tells me the mortifying news that my family, my own family in France, have offered Elizabeth an alliance and a new suitor for her hand. They do not even insist on my release before her wedding. This is to betray me; I am betrayed by my own kin who should protect me. They have offered her Henri d’Anjou, which should be a joke, given that he is a malformed schoolboy and she an old lady, but for some reason, nobody is laughing and everyone is taking it seriously.

Her advisors are all so afraid of Elizabeth dying, and me inheriting, that they would rather marry her to a child and have her die in childbirth, old as she is, old enough to be a grandmother—as long as she leaves them with a Protestant son and heir.

I have to think that this is a cruel joke from my family on Elizabeth’s vanity and lust, but if they are sincere, and if she will go through with it, then they will have a French king on the throne of England, and I will be disinherited by their child. They will have left me in prison to rot and put a rival to me and mine on the English throne.

I am outraged, of course, but I recognize at once the thinking behind this strategy. This stinks of William Cecil. This will be Cecil’s plan: to split my family’s interests from mine, and to make Philip of Spain an enemy of England forever. It is a wicked way to carve up Christendom. Only a heretic like Cecil could have devised it, but only faithless kin like my own husband’s family are so wicked that they should fall in with him.

All this makes me determined that I must be freed before Elizabeth’s misbegotten marriage goes ahead, or if she does not free me, then Philip of Spain’s armada must sail before the betrothal and put me in my rightful place. Also, my own promised husband, Norfolk, must marry me and be crowned King of Scotland before his cousin Elizabeth, eager to clear the way for the French courtiers, throws him back in the Tower. Suddenly, we are all endangered by this new start of Elizabeth, by this new conspiracy of that archplotter Cecil. Altogether, this summer, which seemed so languid and easy, is suddenly filled with threat and urgency.

1570, SEPTEMBER,

CHATSWORTH:

BESS

Abrief visit for the two of them to Wingfield—the cost of the carters alone would be more than her allowance if they ever paid it—and then they are ordered back to Chatsworth for a meeting which will seal her freedom. I let them go to Wingfield without me; perhaps I should attend on her, perhaps I should follow him about like a nervous dog frightened of being left behind, but I am sick to my soul at having to watch my husband with another woman and worrying over what should be mine by right.

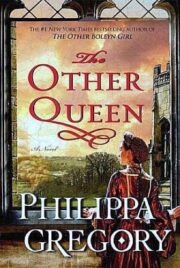

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.