I see Bess’s son Henry and my own son Gilbert, but they are awkward in my presence and I suppose they have heard that I am suspected of betraying my wife with the Scots queen. They are both big favorites with Bess; it is natural that they should take her side against me. I dare not defend myself to them, and after asking them both for their health and if they are in debt, I let them go. They are both well, they both owe money; I suppose I should feel glad.

On the third day of waiting, when they judge that I have suffered enough, one of the ladies-in-waiting comes and tells me that the queen will see me in her private rooms after dinner. I find I cannot eat. I sit in my usual place in the great hall at a table with my equals, but they do not speak to me and I keep my head down like a whipped page. As soon as I can, I leave the table. I go and wait in her presence room again. I feel like a child, hoping for a word of kindness but certain of a beating.

At least I can be assured that I am not to be arrested. I should take a little comfort from that. If she was going to arrest me for treason she would do it in the full council meeting, so that they could all witness my humiliation as a warning to other fools. They would strip me of my titles; they would accuse me of disloyalty and send me away with my cap torn from my head and guards on either side of me. No, this is to be a private shaming. She will accuse me of failing her, and though I can point to my deeds and prove that I have never done anything that was not in her interests or as I was ordered, she can reply by pointing to the leniency of my guardianship of the queen and to the wide and growing belief that I am half in love with Mary Stuart. And in truth, if I am accused of loving her, I cannot honestly deny it. I think that I won’t deny it. I don’t even wish to deny it. A part of me, a mad part of me, longs to proclaim it.

As I thought, it is the gossip of that intimacy that upsets the queen more than anything else. When I am finally admitted into her privy chamber, with her women openly listening, and Cecil at her side, it is the first thing she raises.

“I would have thought that you of all men, Shrewsbury, would not be such a fool for a pretty face,” she spits out, almost as soon as I enter the room.

“I am not,” I say steadily.

“Not a fool? Or does she not have a pretty face?”

If she were a king, these sorts of questions would not be hurled out with such jealous energy. No man can answer such questions to the satisfaction of a woman of nearly forty years whose best looks are long behind her, about her rival, the most beautiful woman in the world and not yet thirty. “I am sure that I am a fool,” I say quietly. “But I am not a fool for her.”

“You let her do whatever she wanted.”

“I let her do what I thought was right,” I say wearily. “I let her ride out, as I was ordered to do, for the benefit to her health. She has grown sick under my care, and I regret it. I let her sit with my wife and sew together for the company. I know for a fact that they never talked of anything but empty chitchat.”

I see the gleam in her dark eyes at this. She has always prided herself in having the intelligence and education of a man.

“Women’s chatter,” I hint dismissively, and see her approving nod. “And she dined with us most nights because she wanted the company. She is accustomed to having many people around her. She is used to a court and now she has no one.”

“Under her own cloth of state!” she exclaims.

“When you first put her into my keeping you ordered me to treat her as a reigning queen,” I observe as mildly as I can. I must keep my temper; it would be death even to raise my voice. “I must have written to you and to Cecil a dozen times asking if I could reduce her household.”

“But you never did so! She is served by hundreds!”

“They always come back,” I say. “I send them away and tell her she must have fewer servants and companions but they never leave. They wait for a few days and then come back.”

“Oh? Do they love her so very much? Is she so beloved? Do her servants adore her, that they serve her for nothing?”

This is another trap. “Perhaps they have nowhere else to go. Perhaps they are poor servants who cannot find another master. I don’t know.”

She nods at that. “Very well. But why did you let her meet with the Northern lords?”

“Your Grace, they came upon us by accident when we were out riding. I did not think any harm would come of it. They rode with us for a few moments; they did not meet with her in private. I had no idea what they were planning. You saw how I took her away from danger the minute that their army was raised. Every word I had from Cecil I obeyed to the letter. Even he will tell you that. I had her in Coventry within three days. I kept her away from them and I guarded her closely. They did not come for her; we were too quick for them. I kept her safe for you. If they had come for her; we would have been undone, but I took her away too quickly for them.”

She nods. “And this ridiculous betrothal?”

“Norfolk wrote of it to me, and I passed on his letter to the queen,” I say honestly. “My wife warned Cecil at once.” I do not say that she did so without telling me. That I would never have read a private letter and copied it. That I am as ashamed of Bess being Cecil’s spy as I am of the shadow of suspicion on me. Bess, as Cecil’s spy, will save me from the shadow of suspicion. But I am demeaned either way.

“Cecil said nothing of it to me.”

I look the liar straight in the face. His expression is one of urbane interest. He inclines forward as if to hear my reply the better.

“We told him at once,” I repeat smugly. “I don’t know why he would have kept it from you. I would have thought he would tell you.”

Cecil nods as if the point is well made.

“Did she think she would make a king of my cousin?” Elizabeth demands fiercely. “Did she think he would rule Scotland and rival me here? Did Thomas Howard think to be King Thomas of Scotland?”

“She did not take me into her confidence,” I say, truly enough. “I only knew that lately she hoped that they would marry with your permission, and that he would help her with the Scots lords. Her greatest wish, as far as I know, has always been only to return to her kingdom. And to rule it well, as your ally.”

I do not say, As you promised she should. I do not say, As we all know you should. I do not say, If only you had listened to your own heart and not to the mean imagination of Cecil, none of this would ever have happened. The queen is not a mistress who cares to be reminded of her broken promises. And I am fighting for my life here.

She gets up from her chair and goes to the window to look out over the road that runs down from the castle. Extra guards are posted at every door and extra sentries at the entrance. This is a court still fearing a siege. “Men I have trusted all my life have betrayed me this season,” she says bitterly. “Men that I would have trusted with my life have taken arms against me. Why would they do that? Why would they prefer this French-raised stranger to me? This queen with no reputation? This so-called beauty? This much-married girl? I have sacrificed my youth, my beauty, and my life for this country, and they run after a queen who lives for vanity and lust.”

I hardly dare to speak. “I think it was more their faith…,” I say cautiously.

“It is not a matter of faith.” She wheels around on me. “I would have everyone practice the faith they wish. Of all the monarchs in Europe I am the only one that would have people worship as they wish. I am the only one who has promised and allows freedom. But they make it a matter of loyalty. D’you know who promised them gold if they would come against me? The Pope himself. He had a banker distributing his gold to the rebels. We know all about it. They were paid by a foreign and enemy power. That makes it a matter of loyalty; it is treason to be against me. This is not a matter of faith, it is a matter of who is to be queen. They chose her. They will die for it. Who do you choose?”

She is terrifying in her rage. I drop to my knee. “As always. I choose you, Your Grace. I have been faithful to you since your coming to the throne, and before you, your sister, and before her, your sainted brother. Before him, your majestic father. Before them, my family has served every crowned king of England back to William the Conqueror. Every king of England can count on a Talbot to stand faithful. You are no different. I am no different. I am yours, heart and soul, as my family always has been to the kings of England.”

“Then why did you let her write to Ridolfi?” she snaps. It is a trap and she springs it, and Cecil’s head droops as he watches his feet, the better to listen to my answer.

“Who? Who is Ridolfi?”

She makes a little gesture with her hand. “Are you telling me you do not know the name?”

“No,” I say truly. “I have never heard of such a person. Who is he?”

She dismisses my question. “It doesn’t matter then. Forget the name. Why did you let her write to her ambassador? She plotted a treasonous uprising with him when she was in your care. You must have known that.”

“I swear I did not. Every letter that I found I sent to Cecil. Every servant she suborned I sent away. My own servants I pay double to try to keep them faithful. I pay for extra guards out of my own pocket. We live in the meanest of my castles to keep her close. I watch the servants, I watch her. I never cease. I have to turn over the very cobblestones of the road leading to the castle for hidden letters; I have to rifle through her embroidery silks. I have to rummage through the butcher’s cart and slice into the bread. I have to be a spy myself to search for letters. And all this I do, though it is no work for a Talbot. And all of it I report to Cecil, as if I were one of his paid spies and not a nobleman hosting a queen. I have done everything you might ask of me with honor, and I have done more. I have humbled myself to do more for you. I have done tasks I would never have believed that one of my line could have done. All at Cecil’s request. All for you.”

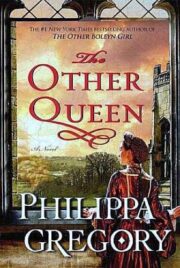

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.