1569, DECEMBER,

COVENTRY:

BESS

So, it is over. Good God, I cannot believe that it is over, and I have my goods safe in my wagons and I can go home again. I have a home to go to. I cannot believe it, but it is true. It is over. It is over, and we have won.

I should have predicted this; I would have predicted it if I had kept my wits about me. But I am a vulgar farmer’s daughter in very truth, and all I could think about was burying the silver and not about the will and the wit of the rival armies. Elizabeth’s army finally arrived on their sluggish march at Durham and sought an enemy to engage and found they had gone, blown away like mist in the morning. The great army of the North marched to meet the Spanish armada at Hartlepool and found nothing. At once they doubted every plan. They had sworn to restore the old church, so they held their Mass and thought that was done. They were for freeing the Scots queen but they were none of them sure where she had gone and they were counting on the Spanish pikemen and Spanish gold. They did not fancy facing Elizabeth’s army without either, and to tell truth they wanted to slip off to their homes and enjoy the peace and prosperity that has come with Elizabeth. They did not want to be the ones to start another war between kin.

Alas for them. The Spanish doubted them and did not want to risk their army and their ships until they were certain of victory. They delayed, and while they hesitated, the Northern army waited at Hartlepool, straining their eyes to see over the white wave tops for the whiter sails, and seeing nothing but the gray skyline and wheeling gulls with the cold spray of the North Sea blowing in their disappointed faces. Then they heard that the Duke of Norfolk had submitted to Elizabeth and written to Westmorland and Northumberland, begging them not to march against their queen. He dropped his head and rode to London though his own tenants hung on his horse’s tail and stirrup leathers and begged him to fight. So there was no Spanish fleet, there was no great army led by the Duke of Norfolk; the Northern army had victory at their very fingertips but they did not know it, and they did not grasp it.

Cecil writes to Hastings to be warned that the country is not at peace, to trust no one, but Westmorland is fled to the Netherlands and Northumberland has gone over the border to Scotland. Most of the men have gone back to their villages with a great story to tell and memories for the rest of their lives and nothing, in the end, achieved. Let a woman, even a vulgar farmer’s daughter, know this: half the time the greater the noise the less the deeds. And grand announcements do not mean great doings.

Let me remember also, in my own defense, that the vulgar farmer’s daughter who buries the silver and understands nothing at least has her silver safe when the great campaigns are over. The army is dispersed. The leaders are fled. And I and my fortune are safe. It is over. Praise God, it is over.

We are to take the queen back to Tutbury for safekeeping before she goes with Hastings to the Tower of London, or wherever he is commanded to take her, and the carters have broken some good Venetian glasses of mine and lost one wagon altogether, which held some hangings and some carpets, but worse than all of this, there is no note from Cecil addressed to us. We are still left in silence, and no word of thanks from our queen for our triumph in snatching the Scots queen from danger. If we had not rushed her away—what then? If she had been captured by the rebels, would not the whole of the North have turned out for her? We saved Elizabeth as surely as if we had met and defeated the army of the North, fifty against six thousand. We kidnapped the rebels’ figurehead and without her they were nothing.

So why does Elizabeth not write to thank my husband the earl? Why does she not pay the money she owes for the queen’s keep? Why does she not promise us Westmorland’s estates? Day after day I tally up her debt to us in my accounts book, and this pell-mell rush across the country did not come cheaply either. Why does not Cecil write one of his warm short notes to send me his good will?

And when we are back in Tutbury with only a few broken glasses, one lost soup tureen, and a wagon full of hangings gone missing, to show for our terror-struck flight—why can I still not feel safe?

1570, JANUARY,

TUTBURY CASTLE:

GEORGE

There is no peace for me. No peace at home, where Bess counts up our losses every day, and brings me the totals on beautifully written pages, as if mere accuracy means they will be settled. As if I can take them to the queen, as if anyone cares that they are ruining us.

No peace in my heart, since Hastings is only waiting for the countryside to be declared safe before he takes the other queen from me, and I can neither speak to her nor plead for her.

No peace in the country, where I can trust the loyalty of no one; the tenants are surly and are clearly planning yet more mischief, and some of them are still missing from their homes, still roaming with ragtag armies, still promising trouble.

Leonard Dacre, one of the greatest lords of the North, who has been in London all this while, is now returned home. Instead of seeing that the battle is over, and lost, even with Elizabeth’s great army quartered on his doorstep, he summons his tenants, saying that he needs them to defend the queen’s peace. At once, as always, guided by the twin lights of his fear and his genius at making enemies, Cecil advises the queen to arrest Dacre on suspicion of treason, and forced into his own defense, the lord raises his standard and marches against the queen.

Hastings bangs open the door into my private room as if I am traitor myself. “Did you know this of Dacre?” he demands.

I shake my head. “How should I? I thought he was in London.”

“He has attacked Lord Hunsdon’s army and got clean away. He swears he will raise the North.”

I feel a sinking fear for her. “Not again! Is he coming here?”

“God knows what he is doing.”

“Dacre is a loyal man. He would not fight the queen’s army.”

“He has just done so and is now an outlaw running for his life like the other Northern earls.”

“He is as loyal as—”

“As you?” Hastings insinuates.

I find that my fists are clenched. “You are a guest in my house,” I remind him, my voice trembling with rage.

He nods. “Excuse me. These are troubling times. I wish to God I could just take her and leave.”

“It’s not safe yet,” I say swiftly. “Who knows where Dacre’s men might be? You can’t take her away from this castle until the countryside is safe. You will raise the North again if they kidnap her from you.”

“I know. I’ll have to wait for my orders from Cecil.”

“Yes, he will command everything now,” I say, unable to hide my bitterness. “Thanks to you, he will be without rival. You have made our steward our master.”

Hastings nods, pleased with himself. “He is without equal,” he says. “No man has a better vision of what England can be. He alone saw that we had to become a Protestant country, we had to separate ourselves from the others. He saw that we have to impose order on Ireland, we have to subordinate Scotland, and we have to go outward, to the other countries of the world, and make them our own.”

“A bad man to have as an enemy,” I remark.

Hastings cracks a brutal laugh. “I’ll say so. And your friend the other queen will learn it. D’you know how many deaths Elizabeth has ordered?”

“Deaths?”

“Executions. As punishment for the uprising.”

I feel myself grow cold. “I did not know she had ordered any. Surely there will be trials for treason for the leaders only, and…”

He shakes his head. “No trials. Those who are known to have ridden out against her are to be hanged. Without trial. Without plea. Without question. She says she wants seven hundred men hanged.”

I am stunned into silence. “That will be a man from every village, from every hamlet,” I say weakly.

“Aye,” he says. “They won’t turn out again, for sure.”

“Seven hundred?”

“Every ward is to have a quota. The queen has ruled that they are to be hanged at the crossroads of each village and the bodies are not to be cut down. They are to stay till they rot.”

“More will die by this punishment than ever died in this uprising. There was no battle, there was no blood shed. They fought with no one, they dispersed without a shot being fired or a sword drawn. They submitted.”

He laughs once more. “Then perhaps they will learn not to rise again.”

“All they will learn is that the new rulers of England do not care for them as the old lords did. All they will learn is that if they ask for their faith to be restored, or the common lands left free to be grazed, or their wages not driven down, that they can expect to be treated as an enemy by their own countrymen and faced with death.”

“They are the enemy,” Hastings says bluntly. “Or had you forgotten? They are the enemy. They are my enemy and Cecil’s enemy and the queen’s enemy. Are they not yours?”

“Yes,” I say unwillingly. “I follow the queen, wherever she leads.” And I think to myself, Yes, they have become my enemies now. Cecil has made them my enemies now, though once they were my friends and my countrymen.

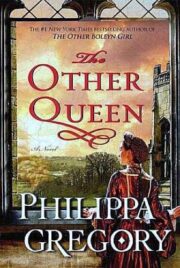

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.