If my husband the earl is suspected, as half the lords of England are suspected, then my fate hangs in the balance with him, with the army of the North, with the destiny of the Queen of Scots. If the Northern army comes upon us soon, we cannot hope to win. We cannot even hold this little city against them. We will have to let them have the queen and whether they take her and put her on the throne of Scotland, or take her to put her on the throne of England, then George and I are alike lost. But equally, if the English army reach us first, then they will take the Queen of Scots from us, since they don’t trust us to guard her, and George and I are lost, dishonored and accused.

My greatest regret, my deep, deep regret in these anxious days, is that we ever agreed to take the Scots queen, that I thought we could manage her, that I thought I could manage my husband with her in the house. My second sorrow is that when he said he would hand all my lands back to me to punish me for doubting his abilities, that I did not say quickly, “Yes!” and get the deed signed then and there. For if—God forbid—if George is kidnapped by the Scots, or accused by the English, or killed in battle, or runs away with the Scots queen for love of her, then either way alike, I shall lose Chatsworth, my house at Chatsworth, my beloved house of Chatsworth. And I would almost rather die myself than lose Chatsworth.

I can hardly believe that having spent all my life marrying for advantage, gathering small parcels of land, storing small pieces of treasure, at the end I should have one of the greatest houses in England and risk it on the whim of the good will of Elizabeth and the good behavior of her cousin, the other queen. When did Elizabeth ever show good will to another woman? When did Mary ever behave well? My fortune rests on two women and I would trust neither of them. My fortune is in the keeping of a man who serves one and loves the other, and is a fool into the bargain. And I must be the greatest fool of all three of them to be sinking into a mire of their making.

1569, NOVEMBER,

COVENTRY:

GEORGE

News at last from Durham, but no good news for us. The army of the North is marching south. They heard their Mass in Durham cathedral and celebrated their triumph with a greatTe Deum , and have now set out with their banners in their strength down the great north road. We must assume they are coming to free the queen. They were seen on the road at Ripon and are said to have four thousand footmen, but their greatest strength is their horse. They have nearly two thousand mounted men, and these are the dazzling young gentlemen of the houses of the North, hardened by years of border raids, trained in the joust, desperate for battle, passionate about their faith, and all of them in love with the Queen of Scots. They are led by Westmorland and Northumberland; even the Countess of Northumberland rides with the army, swearing that we all might as well die in battle than miss this one great chance to restore the true faith.

When I hear this, I truly waver. I feel my heart leap for a moment at the thought of the banners waving and the march of the army for the true church. If only I could be with them, my friends, if only I could have their conviction. If only I could release the queen and ride out with her to join them. What a day that would be! To ride out with the queen to meet her army! But when I imagine this, I have to bow my head and remember that I owe my duty to Queen Elizabeth, I have given my word as a Talbot. I am incapable of dishonor. I would choose death before dishonor. I have to.

Meanwhile Hastings continues to assure me that Elizabeth’s army is on the way north, but no one can say why they are taking so long, nor where they are. My own men are restless; they don’t like this dirty little town of Coventry; I have had to pay them only half their wages since we are desperately short of coin. Bess does her best but the food supplies are poor, and half the men are longing for their homes and the other half yearn to join our enemies. Some of them are already slipping away.

Lord Hunsdon—faithful cousin to the queen—is pinned down by Queen Mary’s supporters in Newcastle; he can’t get west to relieve York, which is on the brink of desperation. The whole of the northeast has declared for Mary. Hunsdon is marching cautiously down the coast, hoping to get to Hull, at least. But there are terrible rumors that the Spanish might land in Hull, and the city would certainly declare for them. The Earl of Sussex is trapped in York; he dare not march out. All of Yorkshire has declared for the army of the North. Sir George Bowes alone has held out against them, and raised a siege at the little market town of Barnard Castle. It is the only town to declare for Elizabeth, the only town in the North of England to prefer her claims to those of the Queen of Scots, but even so, every day his men slip out of the castle gates and run away to join the Papists.

Every day that Elizabeth’s army dawdles reluctantly towards us, the army of the North grows in numbers and confidence and marches onward, faster and faster, greeted as liberating heroes. Every day that Elizabeth’s army delays, the army of the North marches closer to us, and every day increases the chance that the army of the North will get here first and take the Scots queen, and then the war is over without a battle, and Elizabeth is defeated in her own country by her own cousin without the rattle of a sword in her defense. A fine ending to a short reign! A quick conclusion to a brief and unsuccessful experiment with a spinster queen of the Protestant faith! This will be the third child of Henry who has failed to endure. Why should we not try the grandchild of his sister? This will be the second disastrous Protestant Tudor; why should we not go back to the old ways?

Against all this, Bess tells me a little gossip from her steward at Chatsworth, which gives me a tiny glimpse of hope in these hopeless times. He reports to her that half a dozen of the tenant farmers who ran off when the standard of the North was raised have come home, footsore but proud, saying that the rebellion is over. They say that they have marched under the banner of the five wounds of Christ, that they have seen the Host raised in the cathedral at Durham, that the cathedral has been reconsecrated and all their sins have been forgiven, that the good times are here, and wages will be raised, and the Queen of Scots will take the throne of England. They have been greeted as heroes in their villages and now everyone believes that the battle is over and the Queen of Scots has won.

This gives me a moment’s hope that perhaps these simple, trusting people will be satisfied with the capture of Durham and the establishment of the old kingdom of the North and disband. Then we can parley. But I know I am whistling in the dark. I wish to God I had some reliable news. I wish I could be sure that I will be able to keep her safe.

Hastings predicts that the Northern lords are going to establish a kingdom of the North and wait for Elizabeth’s army on the ground of their own choosing. They have the advantage of numbers; they will choose the battlefield as well. They have cavalry, and Elizabeth’s army has next to no horse. The young riders of the North will cut the apprentices of London to pieces. Hastings is grim at this prospect, but anything that delays the battle is good news for me. At least I will not have to face my own countrymen, my friends Westmorland and Percy, in battle today or tomorrow. I am dreading the moment that I have to command men from Derbyshire to sharpen their sickles against men of Westmorland and Northumberland. I am dreading the day that I will have to command men to fire on their cousins. I am certain that my men will refuse.

I abhor the thought of this war. I thought that God might have called me to defend my home against the Spanish or the French, but never did I dream I would find myself in a battle against fellow Englishmen. To threaten a fellow countryman, led by a man I have known for all my life as my friend, will break my heart. Good God, Westmorland and Northumberland have been companions and advisors and kin to me for all my life. We are third cousins and in-laws and stepcousins to each other through five generations. If those two and their kin are out under the flag of the five wounds of Christ, it is unbelievable to me that I am not at their side. I am their brother; I should be beside them.

The battle will come and then I shall have to look over my horse’s ears at their standards, at their beloved, familiar standards, and see them as the enemy. The day will come when I shall see the honest English faces of the other side, and still I shall have to tell my men to prepare to stand against a murderous charge, but it won’t be today. Thank God it won’t be today. But the only reason it is not today is their choice. They are choosing their moment. We are defeated already.

1569, CHRISTMAS EVE,

COVENTRY:

MARY

My chaplain locks my door and my household and I celebrate Mass on this most special night, as if we were Christians in hiding in the catacombs of Rome, surrounded by the ungodly. And like them we know, with utter conviction, that though they seem so powerful, though they seem to dominate the world, it will be our vision that triumphs and our faith that will grow until it is the only one.

He finishes with the bidding prayers and then he wraps up the sacred goods, puts them in a box, and quietly leaves the room. Only his whispered “Merry Christmas” stirs me from my prayer.

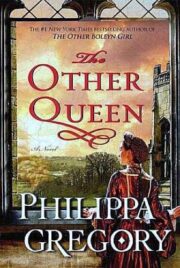

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.