I cannot bear it. I wake in the night and I could weep for it. No infidelity could be worse. Even with the most beautiful woman in Christendom under my roof, I find I think more about whether my husband might lose my fortune than whether he might break my heart. A woman’s heart can mend, or soften, or grow hard. But once you lose your house it is hard to get it back again. If Queen Elizabeth takes Chatsworth from us to punish my husband for disloyalty, I know that I will never set foot in it again.

All very well for him to plot against Cecil like a child with naughty friends, all very well to turn a blind eye to the Queen of Scots and her unending letters. All very well to delight in the company of a woman young enough to be his daughter, and her an enemy of the realm, but to go so far that now the court will not repay us what they owe! They are beyond arguing over the bills; they do not even reply to my accounts. To go so far that they might question our loyalty! Does he think of nothing? Does he not look ahead? Does he not know that a traitor’s goods are at once, without appeal, forfeit to the Crown? Does he not know that Elizabeth would give her own rubies if she could take Chatsworth off me? Has he not given her that excuse with his stupid indiscretion with the Northern lords? Is he not exactly a fool? A wasteful fool? And wasting my inheritance as fast as his own? My children are married to his children, my fortune is in his care: will he throw everything away because he does not think ahead? Can I ever, ever forgive him for this?

I have been married before and I can recognize the moment when a honeymoon is over, when one sees an admired bridegroom for what he is: a mere mortal. But I have never before felt that my marriage was over. I have never before seen a husband as a fool and wished that he was not my lord and master and that my person and my fortune were safe in my own keeping.

1569, OCTOBER,

TUTBURY CASTLE:

GEORGE

However long that I live, I will never forget this autumn. Every leaf that falls has stripped away my pride. As the trees have gone bare, I have seen the bones of my life revealed in darkness, in coldness, without the concealing shimmer of foliage. I have been mistaken. I have misunderstood everything. Cecil is more than a steward, far more. He is a landlord, he is a bailiff. He is bailiff of all England and I am nothing more than a poor copyholder who mistook his long life here, his family’s home, his love of the land, for freehold. I thought I was a landowner here, but I find I own nothing. I could lose everything tomorrow. I am as a peasant—less: I am as a squatter on someone else’s land.

I thought that if we lords of England saw a better way to rule this country than Cecil’s unending readiness for war, Cecil’s unending hatred of all Elizabeth’s heirs, Cecil’s unending terror of boggarts in shadows, Cecil’s mad fear of Papists, then we could topple Cecil and advise the queen. I thought we could show her how to deal justly with the Scots queen, befriend the French, and make alliances with Spain. I thought we could teach her how to live like a queen with pride, not like a usurper haunted with terror. I thought that we could give her such confidence in her right to the throne that she would marry and make an heir. But I was wrong. As Bess obligingly tells me, I was foolishly wrong.

Cecil is determined to throw all who disagree with him into the Tower. The queen listens only to him and fears treason where there was only dissent. She will not consult any one of the lords now; she mistrusts even Dudley. She would behead shadows if she could. Who knows what profit Cecil can make of this? Norfolk is driven from his own cousin’s court, driven into rebellion; the Northern lords are massing on their lands. For me, so far, he reserves only the shame of being mistrusted and replaced.

Only shame. Only this deep shame.

I am beyond distress at the turn events have taken. Bess, who is frosty and frightened, may well be right and I have been a fool. My wife’s opinion of me is another slur that I must learn to accept in this season of coldness and dark.

Cecil writes to me briefly that two lords of his choosing will come to remove the Scots queen into their safekeeping and will take her away from me. Then I am to travel to London to face questioning. He says no more. Indeed, why should he explain anything to me? Does the steward explain to a copyholder? No, he simply gives his orders. If Queen Elizabeth thinks I cannot be trusted to guard the Scots queen, then she has decided that I am unfit to serve her. The court will know what she thinks of me; the world will know what she thinks of me. What cuts me to my heart, my proud unchanging heart, is that now I know what she thinks of me.

She thinks badly of me.

Worse than this is a private, secret pain, of which I can never complain, which I can never even acknowledge to another living soul. The Scots queen will be taken away from me. I may never see her again.

I may never see her again.

I am dishonored by one queen, and I will be bereft of the other.

I cannot believe that I should feel such a sense of loss. I suppose I have become so accustomed to being her guardian, to keeping her safe. I am so used to waking in the morning and glancing across to her side of the courtyard, and seeing her shutters closed if she is still asleep or open if she is already awake. I am in the habit of riding with her in the morning, of dining with her in the afternoon. I have become so taken with her singing, her love of cards, her joy in dancing, the constant presence of her extraordinary beauty, that I cannot imagine how I shall live without her. I cannot wake in the morning and spend the day without her. God is my witness, I cannot spend the rest of my life without her.

I don’t know how this has happened. I certainly have not been disloyal to Bess or to my queen, I certainly have not changed my allegiance either to wife or monarch, but I cannot help but look for the Scots queen daily. I long for her when I do not see her, and when she comes—running down the stairs to the stable yard, or walking slowly towards me with the sun behind her—I find that I smile, like a boy, filled with joy to see her. Nothing more than that, an innocent joy that she walks towards me.

I cannot make myself understand that they will come and take her away from me and that I must not say one word of protest. I will keep silent, and they will take her away and I will not protest.

They arrive at midday, the two lords who will take her from me, rattling into the courtyard, preceded by their own guards. I find a bitter smile. They will learn how expensive these guards are to keep: fed and watered and watched against bribery. They will learn how she cannot be guarded, whatever they pay. What man could resist her? What man could refuse her the right to ride out once a day? What man could stop her smiling at her guardian? What power could stop a young soldier’s heart turning over in his chest when she greets him?

I go to meet them, shamed by their presence, and ashamed of the dirty little courtyard, and then I recoil, recognizing their standards and seeing the men that Cecil has chosen to replace me to guard this young woman. Dear God, whatever it costs me, I cannot release her to them. I must refuse.

“My lords,” I stammer, horror making me slow of speech. Cecil has sent Henry Hastings, the Earl of Huntingdon, and Walter Devereux, the Earl of Hereford, as her kidnappers. He might as well have sent a pair of Italian assassins with poisoned gloves.

“I am sorry for this, Talbot,” Huntingdon says bluntly as he swings down from his saddle with a grunt of discomfort. “All hell is on in London. There is no telling what will happen.”

“All hell?” I repeat. I am thinking quickly if I can say that she is ill or if I dare send her back in secret to Wingfield. How can I protect her from them?

“The queen has moved to Windsor for safety and has armed the castle for siege. She is calling all the lords of England to court, all of them suspected of ill-doing. You too. I am sorry. You are to attend at once, after you have helped us move your prisoner to Leicestershire.”

“Prisoner?” I look at Hastings’ hard face. “To your house?”

“She is no longer a guest,” Devereux says coldly. “She is a prisoner. She is suspected of plotting treason with the Duke of Norfolk. We want her somewhere that we can keep her confined. A prison.”

I look around at the cramped courtyard, at the one gate with the portcullis, at the moat and the one road leading up the hill. “More confined than this?”

Devereux laughs shortly and says, almost to himself, “Preferably a bottomless pit.”

“Your household has proved itself unreliable,” Hastings says flatly. “Even if you are not. Nothing proven. Nothing stated against you, at any rate not yet. Talbot, I am sorry. We don’t know how far the rot has gone. We can’t tell who are the traitors. We have to be on guard.”

I feel the heat rush to my head and for a moment I see nothing, in the intensity of my rage. “No man has ever questioned my honor. Never before. No man has ever questioned the honor of my family. Not in five hundred years of loyal service.”

“This is to waste time,” young Devereux says abruptly. “You will be questioned on oath in London. How soon can she be ready to come?”

“I will ask Bess,” I say. I cannot speak to them; my tongue is dry in my mouth. Perhaps Bess will know how we can delay them. My anger and my shame are too much for me to say a word. “Please, enter. Rest. I will inquire.”

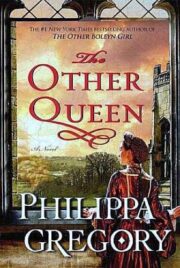

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.