“Exactly!” I chime in. “He is overmighty.”

“Hear yourself! Yes! Think! You say it yourself! He is overmighty. So he is too mighty for you and those fools to pull down. Even acting together. And if he thinks you are against him he will destroy you. He will spin the queen a long yarn and hang the Northern lords for the treason of planning an uprising, punish Norfolk for the treason of this betrothal, and throw you into the Tower forever for being a part of both.”

“I knew nothing of either. All I joined with was a wish to see Cecil reduced. All I said was that I was with them to bring Cecil down.”

“Did you speak to the Northern lords of Norfolk’s marriage to the Queen of Scots?” she demands, as passionately as a wife would force a husband to confess to a secret lover. “When they visited that night? Did you agree with them that it would be a very good thing for Norfolk, and for yourselves, and a bad thing for Cecil? Did you say it would be good for her to take her throne in Scotland with him as her husband? Did you agree that the queen did not know of it? Did you say anything like that?”

“Yes,” I admit, as reluctantly as an unfaithful husband. “Yes, I think I may have done.”

She throws down the napkin to the floor with the thread and the needle. I have never seen her careless with her work before. “Then you have destroyed us,” she says. “Cecil does not have to make it all one plot. Indeed, it is all different strands of the same plot. You passed her letters from Norfolk, you let her meet with the Northern lords, you spoke with them about the marriage, and you agreed to plot with them against the queen’s advisor and against his policy.”

“What should I have done other?” I shout at her in my own fear. “I am for England! Old England, as it was. My country, my old country! I don’t want Cecil’s England, I want the England of my father! What else should I have done but bring him down?”

The face she turns on me is like stone, if stone could be bitter. “You should have kept me and my fortune safe,” she says, her voice quavering. “I came to you with a good fortune, a great fortune, and it was yours by marriage, all yours. A wife can own nothing in her own name. A wife has to trust her husband with her wealth. I trusted you with mine. I trusted you to keep it safe. When we married, all my properties became yours; all you give me is a wife’s allowance. I trusted you with my wealth, with my houses, with my lands, with my businesses. I gave them to you to keep them safe for me and my children. That is all I asked of you. To keep me and my fortune safe. I am a self-made woman. You promised that you would keep my fortune safe.”

“You shall have it all back under your own command,” I swear. I am furious with her, still thinking of money at a time like this. “I shall free myself from this shadow on my name. I shall clear my name and the name of my house. And you shall have your own fortune back as your own again. You shall live apart in your own precious house and count your precious ha’pennies. And you shall be sorry, madam, that you and your great friend Cecil ever doubted me.”

Her face crumples at once. “Oh, don’t say it, don’t say it,” she whispers. She comes to me and at the scent of her hair and the touch of her hand I open my arms and she falls into them, closes herself to me, cries against my chest, a weak woman after all.

“There,” I say. “There, there.” Sometimes I ask too much of her. She is only a woman and she takes strange fearful fancies. She cannot think clearly like a man, and she has no education and no reading. She is only a woman: everyone knows that women have no steadiness of mind. I should protect her from the wider world of the court, not complain that she lacks a man’s understanding. I stroke the smoothness of her hair and I feel my love for her from my bowels to my heart.

“I shall go to London,” I promise her quietly. “I shall take you and the queen to Tutbury, and as soon as her new guardian arrives to replace me, I will go to London and tell the queen herself that I knew nothing of any plot. I am guilty of no plot. Everyone knew what I knew. I shall tell her that all I have ever done is to pray for the return of the England of her father. Henry’s England, not Cecil’s England.”

“Anyway Cecil knew, whatever he says now,” Bess declares indignantly, struggling out from my arms. “He knew of this plot long before it was hatched. He knew of the betrothal as well as any of us, as soon as any of us. He could have scotched it in days, even before it started.”

“You are mistaken. He cannot have known. He learned of it only just now, when Dudley told the queen.”

She shakes her head impatiently. “Don’t you know yet that he knows everything?”

“How could he? The proposal was a letter from Howard to the queen, carried by Howard’s messenger under seal. How could Cecil have learned of it?”

She steps back out of my arms and her glance slides away from me. “He has spies,” she says vaguely. “Everywhere. He has spies who will see all of the Scots queen’s letters.”

“He can’t have done. If Cecil knew everything, from the first moment, then why did he not tell me of it? Why not tell the queen at once? Why leave it till now, and accuse me of being an accomplice in a plot?”

Her brown eyes are hazy; she looks at me as if I were far, far away. “Because he wants to punish you,” she says coolly. “He knows you don’t like him—you have been so indiscreet in that, the whole world knows you don’t like him. You call him a steward and the son of a steward in public. You didn’t bring him the result he wanted from the queen’s inquiry. Then he learns that you are joined with Norfolk and the others in a plot to unseat him from his place. Then he knows that you encourage the queen to marry Norfolk. Then he learns that his sworn enemies, the Northern lords Westmorland and Northumberland have visited you and the queen and been made right welcome. Why would you be surprised that now he wants to throw you down from your place? Do you not want to throw him down from his? Did you not start the battle? Do you not see that he will finish it? Have you not laid yourself open to accusation?”

“Wife!” I reprimand her.

Bess turns her gaze to me. She is not soft and weeping anymore; she is critical and plain. “I will do what I can,” she says. “I will always do what I can for our safety and for our fortune. But let this be a lesson to you. Never ever work against Cecil. He commands England; he has a spy network that covers every house in the land. He tortures his suspects and he turns them to his service. He knows all the secrets; he sees everything. See what happens to his enemies? The Northern lords will go to the scaffold, Norfolk could lose his fortune, and we…” She holds up the letter. “We are under suspicion at the very least. You had better make it clear to the queen and to Cecil that we know nothing of what the Northern lords planned, that they told us nothing, that we know nothing of what they are planning now, and make sure you say that Cecil had a copy of every letter that Norfolk ever sent, the moment that the Scots queen received it.”

“He did not,” I protest stupidly. “How could he?”

“He did,” she says crisply. “We are not such fools as to do anything without Cecil’s permission. I made sure of it.”

I take a long moment to understand that the spy in my household, working for a man that I hate, whose downfall I have planned, is my beloved wife. I take another moment to understand that I have been betrayed by the woman I love. I open my mouth to curse her for disloyalty but then I stop. She has probably saved our lives by keeping us on the winning side: Cecil’s side.

“It was you that told Cecil? You copied the letter to him?”

“Yes,” she says shortly. “Of course. I report to him. I have done so for years.” She turns away from me to the window and looks out.

“Did you not think that you were being disloyal to me?” I ask her. I am exhausted; I cannot even be angry with her. But I cannot help but be curious. That she should betray me and tell me of it without the least shame! That she should be so barefaced!

“No,” she says. “I did not think I was being disloyal, for I was not disloyal. I was serving you, though you don’t have the wit to know it. By reporting to Cecil I have kept us, and our wealth, safe. How is that disloyal? How does it compare to plotting with another woman and her friends against the peace of the Queen of England in your wife’s own house? How does it compare to favoring another woman’s fortune at the price of your own wife’s safety? How does it compare to dancing attendance on another woman every day of your life, and leaving your own wife at risk? Her own fortune half-squandered? Her lands in jeopardy?”

The bitterness in her voice stuns me. Bess is still looking out the window, her mouth full of poison, her face hard.

“Bess…wife…You cannot think I favor her above you…”

She does not even turn her head. “What shall we do with her?” she asks. She nods to the garden and I draw a little closer to the window and see the Scots queen, still in the garden, with a cloak around her shoulders. She is walking along the terrace to look out over the rich woods of the river valley. She shades her eyes with her hand from the low autumn sun. For the first time I wonder why she walks and looks to the north, like this, every day. Is she looking for the dust from a hard-riding army, with Norfolk at their head, come to rescue her and then take her down the road to London? Does she think to turn the country upside down once more in the grip of war, brother against brother, queen against queen? She stands in the golden afternoon light, her cloak rippling behind her.

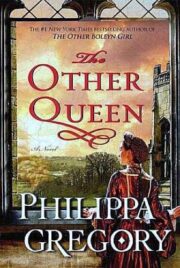

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.