But tonight, for the first time ever, I realize that I am not a young woman anymore. Here, in my own house, in my own great hall, where I should be most at ease in my comfort and my pride, I see that I have become an older woman. No, actually not even that. I am not an older woman: I am an old woman, an old woman of forty-one years. I am past childbearing; I have risen as high as I am likely to go; my fortunes are at their peak; my looks can now only decline. I am without a future, a woman whose days are mostly done. And Mary Queen of Scots, one of the most beautiful women in the world, young enough to be my daughter, a princess by birth, a queen ordained, is sitting at dinner, dining alone with my husband, at my own table, and he is leaning towards her, close, closer, and his eyes are on her mouth and she is smiling at him.

1569, MAY,

WINGFIELD MANOR:

GEORGE

Iam waiting with the horses in the great courtyard of the manor when the doors of the hall open, and she comes out, dressed for riding in a gown of golden velvet. I am not a man who notices such things, but I suppose she has a new gown, or a new bonnet, or something of that nature. What I do see is that in the pale sunshine of a beautiful morning she is somehow gilded. The beautiful courtyard is like a jewel box around something rare and precious, and I find myself smiling at her, grinning, I fear, like a fool.

She steps lightly down the stone stairs in her little red leather riding boots and comes to me confidently, holding out her hand in greeting. Always before, I have kissed her hand and lifted her into the saddle without thinking about it, as any courtier would do for his queen. But today I feel suddenly clumsy, my feet seem too big, I am afraid the horse will move away as I lift her, I even think I may hold her too tightly or awkwardly. She has such a tiny waist, she is no weight at all, but she is tall, the top of her head comes to my face. I can smell the light perfume of her hair under her golden velvet bonnet. For no reason I feel I am growing hot, blushing like a boy.

She looks at me attentively. “Shrewsbury?” she asks. She says it “Chowsbewwy?” and I hear myself laugh from sheer delight at the fact that still she cannot pronounce my name.

At once her face lights up with reflected laughter. “I still cannot say it?” she asks. “This is still not right?”

“Shrewsbury,” I say. “Shrewsbury.”

Her lips shape to make the name as if she were offering me a kiss. “Showsbewy,” she says and then she laughs. “I cannot say it. Shall I call you something else?”

“Call me Chowsbewwy,” I say. “You are the only person ever to call me that.”

She stands before me and I cup my hands for her booted foot. She takes a grip of the horse’s mane, and I lift her, easily, into the saddle. She rides unlike any woman I have ever known before: French-style, astride. When my Bess first saw it, and the manilla pantaloons she wears under her riding habit, my wife swore that there would be a riot if she went out like that. It is so indecent.

“The Queen of France herself, Catherine de Medici, rides like this, and every princess of France. Are you telling me that she and all of us are wrong?” Queen Mary demanded, and Bess blushed scarlet to her ears and begged pardon and said that she was sorry but it was odd to English eyes, and would the queen not ride pillion, behind a groom, if she did not want to go sidesaddle?

“This way, I can ride as fast as a man,” Queen Mary said, and that was the end to it, despite Bess’s murmur that it was no advantage to us if she could outride every one of her guards.

From that day she has been riding on her own saddle, astride like a boy, with her gown sweeping down on either side of the horse. She rides, as she warned Bess, as fast as a man, and some days it is all I can do to keep up with her.

I make sure that her little heeled leather boot is safe in the stirrup, and for a second I hold her foot in my hand. She has such a small, high-arched foot, when I hold it I can feel an odd tenderness towards her. “Safe?” I ask. She rides a powerful horse; I am always afraid it will be too much for her.

“Safe,” she replies. “Come, my lord.”

I swing into the saddle myself and I nod to the guards. Even now, even with the plans for her return to Scotland in the making, her wedding planned to Norfolk, her triumph coming at any day now, I am ordered to surround her with guards. It is ridiculous that a queen of her importance, a guest in her cousin’s country, should be so insulted by twenty men around her whenever she wants to ride out. She is a queen, for heaven’s sake; she has given her word. Not to trust her is to insult her. I am ashamed to do it. Cecil’s orders, of course. He does not understand what it means when a queen gives her word of honor. The man is a fool and he makes me a fool with him.

We clatter down the hill, under the swooping boughs of trees, and then we turn away to ride alongside the river through the woods. The ground rises up before us and we come out of the trees when I see a party of horsemen coming towards us. There are about twenty of them, all men, and I pull up my horse and look back at the way we have come and wonder if we can outride them back to home, or if they would dare to fire on us.

“Close up,” I call sharply to the guards. I feel for my sword but of course I am not wearing one, and I curse myself for being overconfident in these dangerous times.

She glances up at me, the color in her cheeks, her smile steady. She has no fear, this woman. “Who are these?” she asks, as if it is a matter of interest and not hazard. “We can’t win a fight, I don’t think, but we could outride them.”

I squint to see the fluttering standards and then I laugh with relief. “Oh, it is Percy, my lord Northumberland, my dearest friend, and his kin, my lord Westmorland, and their men. For a moment I thought that we were in trouble!”

“Oh, well met!” Percy bellows as he rides towards us. “A lucky chance. We were coming to visit you at Wingfield.” He sweeps his hat from his head. “Your Grace,” he says bowing to her. “An honor. A great honor, an unexpected honor.”

I have been told nothing of this visit, and Cecil has not told me what to do if I have noble visitors. I hesitate, but these have been my friends and my kin for all my life; I can hardly make them strangers at my very door. The habit of hospitality is too strong in me to do anything but greet them with pleasure. My family have been Northern lords for generations; all of us always keep open house and a good table for strangers as well as friends. To do anything else would be to behave like a penny-pinching merchant, like a man too mean to have a great house and a great entourage. Besides, I like Percy, I am delighted to see him.

“Of course,” I say. “You are welcome as ever.” I turn to the queen and ask her permission to present them. She greets them coolly with a small reserved smile and I think that perhaps she was enjoying our ride and does not want our time together interrupted.

“If you will forgive us, we will ride on,” I say, trying to do whatever she wants. “Bess will make you welcome at home. But we won’t turn back just yet. Her Grace values her ride and we have just come out.”

“Please, don’t change your plans for us. May we ride with you?” Westmorland asks her, bowing.

She nods. “If you wish. And you may tell me all the news from London.”

He falls in beside her and I hear him chattering to entertain her, and occasionally the ripple of her laughter. Percy brings his horse alongside mine and we all trot briskly along.

“Great news. She is to be freed next week,” he says to me, a broad smile spread across his face. “Thank God, eh, Shrewsbury? This has been an awful time.”

“So soon? The queen is going to free her so soon? I heard from Cecil only that it would be this summer.”

“Next week,” he confirms. “Thank God. They will send her back to Scotland next week.”

I nearly cross myself, I am so thankful at this happy ending for her, but I cut short the gesture and instead put my hand out to him and we shake hands, beaming. “I have been so concerned for her…Percy, you have no idea how she has suffered. I have felt like a brute to keep her so confined.”

“I don’t think a faithful man in England has slept well since that first damned inquiry,” he says shortly. “Why we did not greet her as a queen, and give her safe haven without asking questions, God knows. What Cecil thought he was doing, treating her like a criminal, only the devil knows.”

“Having us sit as judges on the private life of a queen,” I remind him. “Making all of us attend such an inquiry. What did he want us to find? Three times her enemies brought the filthy letters in secret and asked the judges to read them in secret and make a verdict on evidence that no one else could see. How could anyone do such a thing? To such a queen as her?”

“Well, thank God you did not, for your refusal defeated Cecil. The queen always wanted to be fair to her cousin, and now she finds a way out. Queen Mary is saved. And Cecil’s persecution is thrown back to the Lutherans where it belongs.”

“It is the queen’s own wish? I knew she would do the right thing!”

“She has opposed Cecil from the very beginning. She has always said that the Queen of Scots must have her throne again. Now she has convinced Cecil of it.”

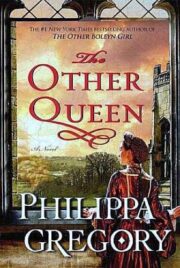

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.