“Are you ill?”

“No,” I say wonderingly. “I think I am well for the first time since you have known me. My heart has stopped aching. The pain is going. I can hope for happiness again.”

He is beaming down at me. “I too am so glad,” he says. “I too. It is as if a shadow has lifted from England, from me…I shall arrange for a guard and the horses to escort you to Scotland. We could leave within the month.”

I smile at him. “Yes, do. As soon as we can. I cannot wait to see my son; I cannot wait to be back in my true place. The lords will accept me, and obey me? They have given their word?”

“They will receive you as queen,” he assures me. “They acknowledge that the abdication was unlawful and forced. And there is something else which should give you greater safety there.”

I wait. I turn my head and smile at him, but I take care not to appear too eager. It is always good to go slowly with shy men; they are frightened by a quick-witted woman.

“I have received a letter addressed to you,” he says in his awkward way. “It comes from the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Howard. Perhaps you are expecting it?”

I incline my head, which could mean yes or no, and I smile up at him again.

“I am at a loss to know what I should do,” he continues, more to himself than to me. “It is your letter. But it has come to me.”

I keep a steady smile. “What is your question?” I ask pleasantly. “If it is my letter?”

“It is the content,” he says heavily. “I cannot in honor deliver a letter which contains unsuitable material. But I cannot, in honor, read a letter which is addressed to another. Especially to a lady. Especially to a queen.”

I swear I could take his troubled face in my hands and kiss away his frown. “My lord,” I say gently, “let me resolve this.” I put out my hand. “I shall open it and read it before you. You shall see the letter yourself. And if you think it was not fit for me to see, then you can take it back and I will forget it, and no harm will be done.” I am burning up to see this letter, but he would never know it from my steady hand and sweet patient smile.

“Very well,” he agrees. He hands it over and steps to one side, puts his hands behind his back like a sentry on duty, and raises himself up on his toes in his embarrassment at having to be guardian and host, all at once.

I see at once that the seal has been lifted and resealed. It has been done with great care but I have been spied on for all my life; not much escapes me. I give no sign that I know my letter has been opened and read by someone else, as I break the seal and unfold the paper.

Dear God, it takes all my long years of training as a French princess to keep my face completely still and calm. In my hands I have a letter of such importance that the words dance before my eyes as I read it and read it again. It is very brief. It is, I think, my pass of safe conduct to guarantee I shall get me out of this bailey on a midden and back to my throne, and my son, and my freedom. Ross said that this would come, and I have been hoping. It is a proposal of marriage. It is my chance for happiness once more.

“You know what he says?” I ask Lord Shrewsbury’s discreetly turned back.

He swings round. “He wrote to me in a covering letter that he was proposing marriage,” he says. “But he has not asked permission of the queen.”

“I don’t need her permission to marry,” I snap. “I am not her subject; she has no command over me.”

“No, but he does. Anyone who is close kin to the throne has to have permission from the queen. And are you not married already?”

“As your inquiry proved, my marriage to Lord Bothwell was forced and invalid. It will be annulled.”

“Yes,” he says uncertainly. “But I did not know that you had rejected Lord Bothwell.”

“He forced the marriage,” I say coldly. “It was made under duress. It is invalid. I am free to marry another.”

He blinks at this sudden clarity and I remember to smile. “I think this a great solution to our difficulties,” I say cheerfully. “Your queen would certainly be confident of me, with her own cousin as my husband. She could be certain of my affection to her and to her country. She could depend on the loyalty of such a husband. And Lord Howard can help me return to my throne in Scotland.”

“Yes,” he says again. “But still.”

“He has money? He says he is a wealthy man. I will need a fortune to pay soldiers.” I could laugh to see Shrewsbury’s delicacy around the sensitive subject of wealth.

“I can hardly say. I have never thought about it. Well—he is a man of substance,” he finally admits. “I suppose it is fair to say that he is the greatest landowner in the kingdom after the queen. He owns all of Norfolk and he has great estates in the North too. And he can command an army, and he knows many of the Scots lords. They trust him, a Protestant, but there are those of his family who keep to your faith. He is, probably, the safest choice of any to help you to keep your throne.”

I smile. Of course I know that the duke owns all of Norfolk. He commands the loyalty of thousands of men. “He writes that the Scots lords themselves suggested this marriage to him.”

“I believe they thought it would give you…”

A man to rule over me, I think bitterly.

“A partner and steady counselor,” says Shrewsbury.

“The duke says that the other peers approve the idea.”

“So he wrote me.”

“Including Sir Robert Dudley? The queen’s great friend?”

“Yes, so he says.”

“So if Robert Dudley gives his blessing to this proposal, then the queen’s approval will certainly follow. Dudley would never involve himself with anything that might displease her.”

He nods. These Englishmen are so slow you can almost hear their brains turning like mill wheels grinding. “Yes. Yes. That is almost certainly so. You are right. That is true.”

“Then we may assume that although the duke has not yet told his cousin the queen of his plans, he will do so soon, with the confidence that she will be happy for him, and that all the lords of her realm and mine approve the marriage?”

Again he pauses to think. “Yes. Almost certainly, yes.”

“Then perhaps we have here the solution to all our troubles,” I say. “I shall write to the duke and accept his proposal, and ask him what he plans for me. Can you see that the letter is delivered for me?”

“Yes,” he says. “There can be nothing wrong in you writing a reply to him, since all the lords and Dudley know…”

I nod.

“If William Cecil knew, I would be happier in my own mind,” he says almost to himself.

“Oh, do you have to ask his permission?” I ask as innocently as a child.

He flares up, as I knew he would. “Not I! I am answerable to none but the queen herself. I am Lord High Steward of England. I am a member of the Privy Council. There is no man placed over me. William Cecil has no power over my doings.”

“Then what William Cecil knows and what he approves are alike indifferent to us both.” I give a little shrug. “He is no more than a royal servant, is he not?” I see his eager nod. “Just the queen’s secretary of state?”

Emphatically, he nods again.

“Then how should his opinion affect me, a queen of the blood? Or you, a peer of the realm? And I shall leave my lord Norfolk when he thinks that the time is right to tell the servants of the queen, Cecil among them. His Grace the duke must be the judge of when he makes an announcement to the servants.”

I stroll back to my seat near the fire and take up my sewing. Bess glances up when I take my seat. My hands are trembling with excitement but I smile calmly, as if her husband was talking of the weather and the chance of hunting tomorrow.

Thank God, thank God who has answered my prayers. This is the way to get me quickly and safely back to my throne in Scotland, back to my son, and with a man at my side who can be trusted by his own ambition and by the power of his family to guard my safety in Scotland and ensure my claims in England. The queen’s own cousin! I shall be married to Elizabeth’s cousin and our sons shall be Stuart children and Tudor kin.

He is a handsome man; his sister Lady Scrope promised me as much when I was with her at Bolton Castle. They said then that the Scots lords who were loyal to me would approach him and ask him if he would take up my cause. They said he would be smuggled into the garden of Bolton Castle so that he could see me. They said that if he saw me he would be certain to fall in love with me and determine at once to be my husband and King of Scotland. Such nonsense, surely! I wore my best gown and walked in the garden every day, my eyes down and my smile thoughtful. At least I do know how to be enchanting; it was my earliest lesson.

He must be a fair man—he was judge at the inquiries and he will have heard every bad thing they said against me, but he has not let it stand in his way. He is a Protestant, of course, but that is only to the good when it comes to dealing with the Scots, and with pressing my claims to inherit England. Best of all, he is used to dealing with a woman who is queen. He was raised as kin to Elizabeth, who was a princess and heir to the throne. He will not bully me like Bothwell, nor envy me like Darnley. He will understand that I am queen and that I need him to be a true husband, an ally, a friend. Perhaps for the first time in my life I will find a man who can love me as a woman and obey me as a queen. Perhaps for the first time I will be married to a man I can trust.

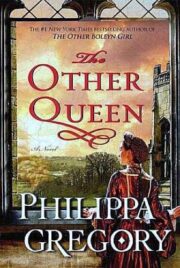

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.