“And children?” she prompts me.

“I have borne eight,” I say proudly. “And God has been good to me and I have six still living. My oldest daughter, Frances, has a babe in arms; they called her Bessie for me. I am a grandmother as well as a mother. And I expect to have more grandchildren.”

She nods. “Then you must think as I do, that a woman who makes herself a barren spinster is flying in the face of God and her own nature, and cannot prosper.”

I do think this, but I am damned if I would say it to her. “I think the Queen of England must do as she prefers,” I declare boldly. “And not all husbands are good husbands.”

I am speaking at random, but I score such a hit at her that she falls silent and then to my horror I see that she has looked away from her sewing and there are tears in her eyes.

“I did not mean to offend you,” she says quietly. “I know full well that not all husbands are good husbands. Of all the women in the world, I would know that.”

“Your Grace, forgive me!” I cry out, horrified by her tears. “I did not mean to distress you! I was not thinking of you! I did not mean to refer to you or your husbands. I know nothing of your circumstances.”

“You must be unique then, for every alehouse in England and Scotland seems to know everything about my circumstances,” she snaps, brushing the back of her hand across her eyes. Her lashes are wet. “You will have heard terrible things about me,” she says steadily. “You will have heard that I was an adulteress against my husband with the Earl of Bothwell, that I urged him to murder my poor husband, Lord Darnley. But these are lies. I am utterly innocent, I beg you to believe me. You can watch me and observe me. Ask yourself if you think I am a woman that would dishonor herself for lust?” She turns her tear-stained beautiful face to me. “Do I look like such a monster? Am I such a fool as to throw honor, reputation, and my throne away for the pleasure of a moment? For a sin?”

“Your life has been much troubled,” I say weakly.

“I was married as a child to the Prince of France,” she tells me. “It was the only way to keep me safe from the ambitions of King Henry of England: he would have kidnapped me and enslaved my country. I was brought up as a French princess; you cannot imagine anything more beautiful than the French court—the houses and the gowns and the wealth that was all around me. It was like a fairy tale. When my husband died it all ended for me in a moment, and then they came to me with the news that my mother had died too, and I knew then that I would have to go home to Scotland and claim my throne. No folly in that, I think. No one can reproach me for that.”

I shake my head. My women are frozen with curiosity, all their needles suspended and their mouths open to hear this history.

“Scotland is not a country that can be ruled by a woman alone,” she says, her voice low but emphatic. “Anyone who knows it knows that to be true. It is riven with faction and rivalry and petty alliances that last for the length of a murder and then end. It is barely a kingdom; it is a scatter of tribes. I was under threat of kidnap or abduction from the first moment that I landed. One of the worst of the noblemen thought to kidnap me and marry me to his son. He would have shamed me into marriage. I had to arrest him and execute him to prove my honor. Nothing less would satisfy the court. I had to watch his beheading to prove my innocence. They are like wild men; they respect only power. Scotland has to have a merciless king, in command of an army, to hold it together.”

“You cannot have thought that Darnley…”

She chokes on an irresistible giggle. “No! Not now! I should have known at once. But he had a claim to the English throne; he swore that Elizabeth would support him if we ever needed help. Our children would be undeniable heirs of England from both his side and mine; they would unify England and Scotland. And once I was married I would be safe from attack. I could not see otherwise how to protect my own honor. He had supporters at my court when he first arrived, though later, they turned against him and hated him. My own half brother urged the marriage on me. And yes—I was foolishly mistaken in him. He was handsome and young and everyone liked him. He was charming and pretty-mannered. He treated me with such courtesy that for a moment it was like being back in France. I thought he would make a good king. I judged, like a girl, on appearances. He was such a fine-looking young man; he was a prince in his bearing. There was no one else I would have considered. He was practically the only man I met who washed!” She laughs and I laugh too. The women breathe an awed giggle. “I knew him. He was a charming young man when he wanted to be.”

She shrugs her shoulders, a gesture completely French. “Well, you know. You know how it is. You know from your own life. I fell in love with him,un coup de foudre . I was mad for him.”

Silently, I shake my head. I have been married four times and never yet been in love. For me, marriage has always been a carefully considered business contract, and I don’t know whatcoup de foudre even means, and I don’t like the sound of it.

“Well,voilа , I married Darnley, partly to spite your Queen Elizabeth, partly for policy, partly for love, in haste, and regretted it soon enough. He was a drunkard and a sodomite. A wreck of a boy. He took it into his stupid head that I had a lover and he lighted upon the only good advisor I had at my court, the only man I could count on. David Rizzio was my secretary and advisor, my Cecil if you like. A steady good man that I could trust. Darnley let his bullies into my private rooms and they killed him before my very eyes, in my chamber, poor David…” She breaks off. “I could not stop them, God knows I tried. The men came for him and poor David ran to me. He hid behind me, but they dragged him out. They would have killed me too: one of them held a pistol against my belly, my unborn son quickening as I screamed. Andrew Kerr his name was—I don’t forget it, I don’t forgive him. He put the barrel of his pistol to my belly and my little son’s foot pressed back. I thought he would shoot me and my unborn child inside me. I thought he would kill us both. I knew then that the Scots are beyond ruling, they are madmen.”

She holds her hands over her eyes as if to block out the sight of it even now. I nod in silence. I don’t tell her that we knew of the plot in England. We could have protected her, but we chose not to do so. We could have warned her but we did not. Cecil decided that we should not warn her, but leave her, isolated and in danger. We heard the news that her own court had turned on her, her own husband had become corrupt, and it amused us: thinking of her alone with those barbarians. We thought she would be forced to turn to England for help.

“The lords of my court killed my own secretary in front of me, as I stood there trying to shield him. Before me—a Princess of France.” She shakes her head. “After that it could only get worse. They had learned their power. They held me captive; they said they would cut me in pieces and throw my body in bits from the terrace of Stirling Castle.”

My women are aghast. One of them gives a little sigh of horror and thinks about fainting. I scowl at her.

“But you escaped?”

At once she smiles a mischievous grin, like a clever boy. “Such an adventure! I turned Darnley back to my side and I had them lower us out of the window. We rode for five hours through the night, though I was six months pregnant, and at the end of the road, in the darkness, Bothwell and his men were waiting for us and we were safe.”

“Bothwell?”

“He was the only man in Scotland I could trust,” she says quietly. “I learned later he was the only man in Scotland who had never taken a bribe from a foreign power. He is a Scot and loyal to my mother and to me. He was always on my side. He raised an army for me and we returned to Edinburgh and banished the murderers.”

“And your husband?”

She shrugs. “You must know the rest. I could not part from my husband while I was carrying his child. I gave birth to my son and Bothwell guarded him and me. My husband Darnley was murdered by his former friends. They planned to kill me too but it happened I was not in the house that night. It was nothing more than luck.”

“Terrible, terrible,” one of my women whispers. They will be converting to Papacy next out of sheer fellow feeling.

“Yes indeed,” I say sharply to her. “Go and fetch a lute and play for us.” So that gets her out of earshot.

“I had lost my secretary and my husband, and my principal advisors were his murderers,” she said. “I could get no help from my family in France, and the country was in uproar. Bothwell stood by me, and he had his army to keep us safe. Then he declared us married.”

“Were you not married?” I whisper.

“No,” she says shortly. “Not by my church. Not in my faith. His wife still lives, and now another one, another wife, has thrown him into prison in Denmark for breach of promise. She claims they were married years ago. Who knows with Bothwell? Not I.”

“Did you love him?” I ask, thinking that this is a woman who was once a fool for love.

“We never speak of love,” she says flatly. “Never. We are not some romantic couple writing poetry and exchanging tokens. We never speak of love. I have never said one word of love to him nor he to me.”

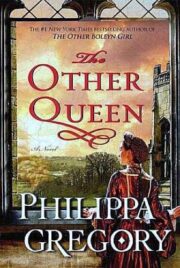

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.