With great effort, like a man with the ague, Querelle lowered his head down and then lifted it up again.

“You appear cold, Monsieur Querelle,” said Delaroche. He gestured to the guard. “You! Fetch our friend a blanket. It wouldn’t do to have him catch a chill. Not now that he has agreed so generously to assist us.”

Something in Delaroche’s voice made the condemned man shudder harder than ever. Which was, of course, exactly what it had been meant to do.

Cutting in front of Delaroche, André plucked the blanket from the hands of the guard and handed it to the condemned man. Querelle’s hands shook as he attempted to arrange the square of wool around his shoulders.

“I do hope you will justify our confidence in you, Monsieur Querelle,” said André quietly. “I should hate to think that you were abusing the generosity of the First Consul.”

“There was a plot,” Querelle said slowly.

This was it, the point of no return. André could see Querelle’s hesitation; it leached out of every line of his body. Venal the man might be, but these had been his comrades. He had endured four months of questioning without breaking. The interrogators at the Temple, where Querelle had been held until now, were seldom gentle in their methods.

Squick, squick, went the sound of wet sawdust being swept off the scaffold below. The sawdust was matted black with blood. The red ran down with the rain, staining the sides of the platform.

Querelle turned back to André. “There was a plot. A conspiracy,” he elaborated.

“To kill the First Consul?” asked André, holding up a hand to silence Delaroche.

“Oh no! N-no!” It would, thought André, be rather cheeky to admit to attempting to kill the same man from whom one was currently seeking a pardon. “We were just going to, er, kidnap him.”

“A likely story,” sneered Delaroche. “Think about it. Think hard.”

The prisoner gathered the tattered shreds of his courage. He had only one card to play, and he knew it. “I’ll think better once that pardon is signed,” he said.

Delaroche’s lips tightened.

“This might be for the best,” interjected André, turning so that he stood between Delaroche and the prisoner. In a low voice, he said, “I can stay and speak to him while you go to Fouché with the good news.”

Delaroche’s eyes narrowed. “The good news?”

André kept his face carefully bland. “That you were able to get Monsieur Querelle to talk. After four months of silence.”

Delaroche smiled at André, one of those lifts of the lips that never quite reaches his eyes. “I couldn’t have done it without your . . . assistance.”

“Be sure to relay that to my cousin,” said André drily, and was rewarded by a tightening at the corners of Delaroche’s mouth. The reminder of that relationship never ceased to annoy him, which was precisely why André never ceased to employ it.

Delaroche moved backwards towards the door. “Fouché will want details. Names, dates, places. Monsieur Querelle would be wise to leave nothing out. Otherwise . . . What is a pardon, after all, but a scrap of paper? Paper tears, it blots, it burns. Paper is a fragile thing.” Delaroche’s eyes bored into the prisoner’s. “Much like a man’s life.”

“Or the passage of time,” said André pointedly, jangling the links of his watch chain. The evil speeches did begin to wear on one after a while. “It wouldn’t do to keep my cousin waiting.”

Delaroche refused to allow himself to be rushed. “So many things are fragile, Monsieur,” he said meditatively. “The things of innocence in this world wither too soon away. A man’s loyalties . . . a child’s laughter.” He looked to André, the long lines of malice graven in his face all the more apparent in the uneven candlelight. “We would all do well to remember that.”

André had the uneasy feeling that Delaroche was no longer talking about the prisoner.

Chapter 3

When Laura presented herself at the Hôtel de Bac the following morning, the only one who seemed the least bit pleased to see her was Pierre-André. Even his enthusiasm waned when he discovered she hadn’t come bearing sweets.

“Never had a governess before,” grumbled Jeannette, the white lappets of her cap bobbing. She remained pointedly in her chair before the fire, her elbows sticking out over her knitting. She was a tall, raw-boned woman, the lace of her cap incongruous next to the masculine contours of her face. “Poor poppets. As if they haven’t had enough to get used to.”

Jean the gatekeeper spat on the floor to signal either his agreement or his antipathy for Jeannette. It was hard to tell, since his basic scowl never changed. Without a further word, he disappeared the way he had come.

Pity. Laura had almost got used to him.

Laura set her portmanteau down on the parquet floor and smiled determinedly at the inhabitants of the nursery. No one smiled back except Pierre-André, but his smile was directed more to Laura’s pockets than her person. He had obviously been bribed by indulgent adults before.

The rooms appropriated for the nursery were on the second story, just above the grand reception rooms. In other days, they might have been the suite of the Marquise de Bac. The day nursery—now schoolroom, Laura corrected herself—had been paneled in pale pink, with delicate plasterwork designs of bouquets of flowers outlined in flaking green, gold, and red paint. In the sunlight, the air of dilapidation hanging over the Hôtel de Bac was even more apparent than it had been the night before. The plasterwork was dingy, the upholstery frayed, and the windows could have done with a wash. But the nursery, at least, was warm. Whatever allowance for coal the household was afforded had gone straight to the nursery grate. For the first time since coming to Paris, Laura felt the blue tinge leaving her skin.

Although that might also have been because she was still in her coat, neither Jean nor Jeannette having made any offer to take it from her.

Unlike the rest of the house, someone had made an effort to render the nursery habitable. The small chairs and table were cheap and modern but new. A large doll’s house sat on a low table and there were already toy soldiers, a hobby horse, and a series of paper cutouts scattered across the floor. A rug covered the hard boards of the floor, protecting tender feet and knees from splinters; and curtains, stiff in their newness, hung in ruffles across the windows. A little boy with a mop of brown curls was engaged in coaxing a toy on a string on a bumpy journey across the hearth rug. His sister, oblivious, pulled up her knees beneath her skirt and went on with her reading.

It would have been a charming scene, the nurse knitting by the fire, the little boy tugging at his horse, the girl reading on the rug, but for the matching scowls on the faces of the women in the room.

“Good day,” Laura said in clear, crisp tones. “My name is Mademoiselle Griscogne and I am to be your new governess.”

Jeannette sniffed.

Abandoning his toy, the little boy launched himself at Laura’s legs. “Do you have sweets?” he asked winningly. It was clearly a ploy that had worked for him before.

Laura detached him from her lower limbs before he could go prospecting for pockets. “Good day, Monsieur Jaouen. Shall I teach you how to properly greet a lady?”

Pierre-André’s forehead creased. “I’m not Monsieur Jaouen,” he said apologetically. “I’m Pierre-André.”

There had evidently been some mistake and it fell to him to remedy it, even if it reduced the possibility of sweets.

“But someday,” said Laura, “you will be Monsieur Jaouen. I am here to help you accomplish that.”

Pierre-André looked uncertainly at his nurse. “I like being me.”

“You will still be you,” Laura assured him. “Just an older, wiser, grander you.”

Pierre-André considered. “Grand as in big?”

“Very big,” Laura promised gravely.

“Big as a house?”

Laura thought of Hamlet, banded in a nutshell, but king of infinite space. “Not in size, but certainly in spirit.”

Jeannette sniffed.

Laura turned to the girl by the hearth, who hastily jerked her book up so that it covered the whole of her face, only her eyebrows visible above the red morocco binding.

“You must be Gabrielle,” said Laura, a little bit to the eyebrows, but mostly to the book.

The book slid down just far enough to reveal a pair of scornful blue eyes.

“Don’t you mean Mademoiselle Jaouen?” Gabrielle said, in what would have been a fine show of defiance if she hadn’t marred it by glancing for ratification at Jeannette.

Jeannette smirked her approval. Gabrielle’s hunched shoulders straightened.

“No,” said Laura pleasantly. “Because Mademoiselle Jaouen would have stood to greet a stranger in her schoolroom. A little girl who hides behind her book can only be Gabrielle.”

Jeannette bristled. “It’s the nursery, not a schoolroom.”

“No,” said Laura. She had the feeling she would be getting a lot of use out of that syllable. She addressed herself to the children. Gabrielle, book at half mast, was regarding her with open hostility. Pierre-André was busy trying to be a house. “From now on, this will be your schoolroom. You obviously have much to learn.”

Gabrielle’s eyes narrowed.

Good, thought Laura. Plot revenge. Think of ways to get me back. Nothing served as a better spur to learning than a strong dose of competition.

“Schoolroom, indeed,” muttered Jeannette. “That’s no way for children to live, locked up in a schoolroom, no fresh air, no playmates. Disgraceful, I call it.”

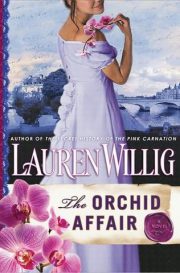

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.