“In other words,” said Daubier, stepping forward, “our conspiracy was discovered. It was,” he added, “through my carelessness.”

Laura looked at Daubier with surprise. It was the first time she had heard him say such a thing. Recovering herself, she gestured from Daubier to Lord Richard. “Lord Richard, this is Monsieur Antoine Daubier, the painter. And that young lady over there is Mademoiselle Gabrielle Jaouen.”

“Mademoiselle.” Lord Richard bowed with debonair flair.

Laura automatically turned towards André to share a smile and encountered nothing but stone. That’s right. They weren’t on smiling terms anymore.

“We are forced to throw ourselves on your mercy,” said Jaouen to Lord Richard. “In fact—”

“Fair enough,” said Lord Richard convivially. “I’m glad to have you on board. In both senses. And you, Miss Grey. Well done!”

Laura brushed aside the praise. “We have a problem,” she said brusquely. “Monsieur Delaroche has Monsieur Jaouen’s son.” It felt strange referring to André by his last name, but stranger to call him by his first. She was Miss Grey again—English operative, governess, spinster. The woman who had curled up naked next to André Jaouen didn’t exist anymore. The woman he had thought he loved was a lie. “He wants the duke in exchange.”

“And your blood, no doubt,” Lord Richard said soberly, turning to André. “How long ago did he take him?”

“Roughly an hour ago. His nursemaid is with him. Will you help us?” asked Laura.

“It will be my pleasure,” said Lord Richard, without mockery. “No man should make war on children.”

A powerful emotion passed across André’s face. “I’m in your debt, Selwick.”

The former Purple Gentian was instantly all action. “Don’t start tallying the IOU until we get him out. Where is he being held?”

“Delaroche has him on a boat called the Cauchemar,” Laura jumped in. “Here in the harbor.”

There was a glint in the former Purple Gentian’s eye that boded ill for Gaston Delaroche. “What do you say we give Monsieur Delaroche a little surprise?”

Chapter 32

Gaston Delaroche never did anything by halves.

André identified the Cauchemar long before they reached it. It wasn’t just the tricolore flying from the mast or the uniformed guards standing sentinel on the pier or even the large, curling black script proclaiming the boat’s name. It was the size of the ship—double the size of the Bien-Aimée—and the fact that it was hung with lanterns, every single one ablaze.

The crews of the boats docked to either side must have just loved that.

Sarcasm kept André’s palms from sweating; sarcasm kept him from imagining what horrors Delaroche had in store for Pierre-André; sarcasm gave him the presence of mind to pretend to stay reasonably calm and nod in the right places when Lord Richard Selwick spoke to him.

He had never thought he would one day make common cause with the Purple Gentian. They had been adversaries not so very long ago. Courteous adversaries. If anything, André had owed the man a debt of gratitude—not just for the amusement value of some of his exploits, but for distracting Delaroche. Whether the Purple Gentian knew it or not, he had unintentionally facilitated more than one objective for the Comte d’Artois, simply by keeping Delaroche occupied elsewhere. False information had been passed, networks of informers assembled, plots plotted, all while Delaroche was busy chasing the shadow of a cheeky purple flower.

What was it they said? The enemy of my enemy is my friend. André had cause tonight to be grateful for that old adage. If the Purple Gentian helped him retrieve his son, he wouldn’t have another thing to say about gentleman adventurers and unpronounceable essays in botany.

There were five of them in the dinghy.

His Royal Highness, Charles Ferdinand d’Artois, Duc de Berry, was not one of the party. De Berry had offered to come, but without marked enthusiasm. He had been more than happy to be persuaded to stay behind to guard the women and children.

De Berry might not have been so sanguine had he known André’s real reasoning. De Berry was their bargaining chip, the only genuine leverage André possessed. Delaroche might want to wreak his revenge on André, but when it came down to it, a prince of the blood was a prize not to be missed—at least, not if one didn’t want to risk Fouché’s extreme disapprobation. No one wanted to risk the disapprobation of Fouché.

When it came down to it, if he had to, André would trade the prince for his son.

He hadn’t told de Berry that, of course. It was a last resort.

Daubier, unlike de Berry, had flatly refused to be left behind. “I have a grudge to settle,” he had said, displaying his hand to Lord Richard.

No one had argued with him.

André, Daubier, and Lord Richard had been joined in the dinghy by two of Lord Richard’s crew—one of whom appeared to be somewhat inexplicably dressed as a pirate, complete with a stuffed parrot on one shoulder. The parrot was held in place by an ingenious mechanism of straps, although it did list a bit to one side as the man rowed. It made André feel a great deal less conspicuous in the sagging remains of his Il Capitano costume.

There had been room for one more in the boat, a place that Laura had tried to claim as her own. She had desisted when Lord Richard had pointed out, apologetically, that her combat training was fairly rudimentary.

Combat training?

Who in the hell was this Laura? Not Laura, André reminded himself. Miss Grey. Miss Grey, who somehow knew the Purple Gentian—not only knew him, but was on terms of some intimacy.

She still looked the same, still dressed in her Ruffiana costume, the skirts kilted up so they wouldn’t trail, her hair scraped back so tightly that it made her eyes slant up at the corners. She had the same little curls at the nape of her neck, the same beauty mark at the corner of one eyebrow, the same eyes, the same nose, the same hands, the same lips that he had kissed again and again, and which, it seemed, had returned to him not just kisses, but kisses and lies.

André wondered just how much had been a lie.

Not that it mattered, André reminded himself, as the dinghy drew towards the brightly lit Cauchemar. It couldn’t be allowed to matter, not even if his guts felt like they had been wrenched out and used for garters. All that mattered was that they save Pierre-André.

“Right-ho,” Lord Richard said, speaking in a voice just barely audible above the sound of the boats rocking in the water. The wind had risen, and waves were slapping against the keels of the boats moored in the harbor. “Here’s the plan. I’ve sent two men along the pier. In precisely ten minutes”—Lord Richard consulted his pocket watch—“they will cut the ropes mooring the Cauchemar.”

Thus making it impossible for the guards on the pier to intervene. Unless, of course, they felt like a swim. André somehow doubted that they did. Delaroche seldom paid well.

“Then what?” André asked.

“As soon as the Cauchemar is floating free, we’re going to make a bit of a fire on the deck to draw off the guards.”

André saw one rather large problem with that. “What if the fire spreads?”

Lord Richard produced a wide and shallow bowl, in which someone appeared to have dumped a pile of greasy rags. “It won’t, unless some idiot is fool enough to overturn the bowl. If we do this correctly, it should produce a great deal of thick, black smoke but very little fire. It ought, however, take them some time to realize that. Nothing spooks a sailor like fire on board ship. Stiles?”

“Arrrrr?” said the pirate interrogatively.

Lord Richard rolled his eyes slightly, but forbore to comment. “I’ll expect you and Pete to be standing by. When the guards show any sign of returning to their posts, tackle them. Make sure they don’t make it below deck.”

“Aye, aye, Cap’n!” The parrot wobbled as the pirate saluted.

Lord Richard looked pained. “Oh, and, Stiles?”

“Cap’n?”

“You might want to leave the parrot in the dinghy. Just a thought.” Turning to André, he said, “We three will seek out Delaroche and free the captives.”

“Your experience with boats is greater than mine,” said André. It would be impossible for it not to be; to his knowledge, he had never been on one. All his travel had been accomplished on land. “Where will he have them? And how do we get to them without being seen?”

Lord Richard nodded. “Despite its size, the Cauchemar seems to be a fairly simple model. There are two possible places that Delaroche might be holding your son. He could be in the main cabin, to the rear, here.” Lord Richard sketched a diagram on the planks of the dinghy with a finger dipped in water. “Or here, in the hold.” He sketched a second rectangle below the first. “If I know my Delaroche, he’ll have them in the hold. It’s the closest he can get to a dungeon.”

It sounded like a logical enough conclusion, but for one thing. “Delaroche doesn’t follow any known rules of logic these days,” André warned. “Your escape sent him around the bend. That, and being separated from his interrogation chamber. They made him pack up his Iron Maiden. It has rendered him . . . unpredictable.”

“You can certainly say that,” said Lord Richard slowly, squinting at the ship. They were drawing steadily closer, the muffled oars making little noise in the water. He pointed towards the deck. “Look at that.”

At first, all André saw were the guards—at least a dozen of them. There were four directly in his line of vision, playing a game that seemed to involve round discs and a mop. As one hit the disc in a broad sweep, the others followed, leaving André a clear view of the mast. The sails were furled, but that wasn’t what created the strange bulk at the bottom.

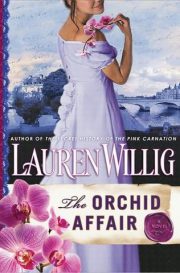

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.