She had been a very different girl, that Laura, the one who had dallied with Antonio in Como.

She had thought she was done with that, that she had frozen it out of her blood. That was what was so terrifying—not the memory of desire, but the reawakening of it, like fire in the blood.

When André had kissed her, up against the wall, she had wanted to take him by the ears and yank his head back down to hers.

Laura let herself into her room. It was a simple enough accommodation, but it had amenities she had all but forgotten, like a proper bed with proper sheets and a fireplace with real logs in it. There was even a mirror on one wall, dirty and tarnished, but still a mirror. Laura grimaced at the sight of herself. There were sweat stains under the arms of her blouse and mud on her skirt. Her hair had been washed—water was one thing they hadn’t lacked along the way—but the damp air had turned it into a frizzy tangle. She looked like a gypsy. Not just a gypsy, but a gypsy who had fallen on hard times.

Someone had brought up her meager bag and placed it on a chair. After six days of wearing the same clothes, Laura ferreted through, marveling over the items she had so naively packed before leaving the Hôtel de Bac. There were three dresses—gray—and chemises and stockings. There were two nightgowns and, beneath those, a slim, paper-bound volume of poetry.

Ronsard. He who believed in gathering one’s flowers while one may.

Well, one could seize the day in multiple ways. Laura untied the strings at the neck of her blouse. It felt like heaven, peeling off the stiff, dirty fabric. There was a basin on the nightstand, with a cloth beside it, and Laura gratefully sponged off some of the dirt of travel. The tapes on her skirt followed. Should she be worried that the skirt could practically stand by itself by now?

It felt almost decadent to let the nightdress slide down over naked flesh, even though, like all her clothes, the nightdress was heavy and serviceable, made of thick, opaque cloth. There wasn’t anything the least bit suggestive about it.

It was ridiculous that she wished there was.

It might be rather nice to be Suzette for a bit, rather than Laura, to seize her pleasure where she could find it and think nothing of the morning. What did she have to lose, after all? She had no family, no obligations. There were no chaperones to wag their fingers or employers to threaten her with dismissal. She was utterly afloat in the world, and that circumstance might be as freeing as it had formerly seemed constraining.

Laura made a face at herself in the mirror. Yes, that was all very well, but with whom? She doubted André would be coming to bed. Not tonight.

And even if he did . . . well, he was coming to bed, not coming to bed.

This was what came of associating with actors.

On an impulse, Laura took up the book of poetry as she clambered into the high, tester bed. She could always read about it if she couldn’t live it.

Ah, time is flying, lady, time is flying / Nay, tis not the time that flies but we . . . Be therefore kind, my love, whilst thou art fair.

So much time already gone. So many dull and dry and barren years. Ronsard, dust now these two-hundred-odd years, had known that.

Shall I not see myself clasped in her arms / Breathless and exhausted by love’s charms....

Laura plumped up the pillows behind her, finding them less comfortable than she had before. The fire was burning down again. It seemed symbolic. That was the problem with poetry. It made everything seem symbolic.

Why hadn’t she just grabbed him and kept kissing him while she had the chance?

Laura grimly turned her eyes again to her book. Sermons, that was what she should have brought with her. Or political economy. Not this, not flowers and kisses and breathless embrace.

She skimmed the next few lines. Kissed by desire . . . breast to breast . . . quenching fire . . . Goodness, it was warm, wasn’t it?

A squeaking noise sent her bolting upright against the pillows, the book clamped shut over one finger.

The door eased open.

Chapter 28

My mouth fell open.

Colin looked as though someone had just socked him in the stomach. Around us, the other party guests obediently lifted their glasses in a toast to Selwick Hall and then drifted on, returning to their drinking, their gossiping, their posturing, entirely unaware that a grenade had just been lobbed into their midst.

“Selwick where?” I heard one woman murmur to another.

The other shrugged, showing off her narrow shoulder bones to good advantage. “Jeremy’s family place, I think.”

Jeremy’s family place? Admittedly, he was a Selwick too, if only on his mother’s side, but it sure as hell wasn’t his. He didn’t live there. And he didn’t have the right to promise it to some film company.

At least, I didn’t think he did. Did he?

Colin stepped up to Jeremy, taking care, even in the midst of chaos, not to make a scene. “You can’t do that. You have no authority to contract for the use of Selwick Hall.”

Jeremy took a cool sip of his champagne. “I might not. But your mother does.”

And where was Colin’s mother? Didn’t she realize how this decision would have gutted her oldest offspring? Selwick Hall was his home—more than his home. I peered around for her. She was still there—she hadn’t slunk off to wash the blood from her hands or go hide behind an arras or whatever it was that disloyal Shakespearean queens were meant to do—happily chattering away at the center of a circle of adoring friends.

“. . . lovely this time of year,” I could hear her saying. I didn’t think she was talking about Selwick Hall. The tan she was sporting didn’t come from spring in Sussex.

“My mother only has a third share.”

“Legally,” said Jeremy, “that’s irrelevant. Any one tenant has full rights to the whole.” His teeth were too white. They sat too straight in his smiling mouth. “But let’s not talk of the legalities. Legalities have no place among family.”

“Did you tell your solicitor that before or after you phoned him?” said Colin curtly.

Jeremy’s smile didn’t falter. “I’d be a fool not to dot the I’s and cross the T’s on a deal like this.”

“There is no deal,” said Colin. “I may not have consulted my solicitor, but I feel fairly safe in guessing that letting out the house to a film crew doesn’t constitute normal enjoyment of the property.”

Not knowing much about English law post-1815, I couldn’t have said whether he was right or not, but it certainly sounded good.

“As I was saying,” said Jeremy, with the sort of chiding tone more appropriate from governess to pupil than from lying snake to stepson, “even assuming your mother doesn’t have the right, on her share alone, to promise Selwick Hall, wouldn’t you agree that majority vote rules?”

“Since when is one-third a majority?” I blurted out.

“One-third may not be a majority,” said Jeremy, never taking his eyes off Colin. “But two-thirds is. You can’t argue with that.”

If Colin had one-third and Colin’s mother had one-third . . . It was like a Sesame Street math problem, only one in which the Muppets had gone rogue, quibbling over the ownership of the letter S.

I didn’t need a map to point the way to the owner of the deciding one-third interest. It would have been obvious, even if Serena hadn’t looked as though she were trying to disappear into her own shawl. Guilt was written all over her face.

“Serena?” Colin turned to his sister. “You don’t know anything about this. Do you?”

It was clear that he expected the answer to be in the negative, despite all indications. My heart ached for him. Don’t tell me organs don’t work that way; I could feel it as a physical squeeze in my chest. I wanted to wrap Colin up in my pashmina and whisk him away from the whole gruesome scene, transport him safe and whole to Selwick Hall.

Which wasn’t, it seemed, entirely his, or entirely safe.

Did this also mean the others could sell it if they took the notion? It was a truly alarming thought. For them it was all a lark—a source of status and prestige or, in this case, spare cash. For Colin, it was home.

After his father’s death, Colin had given up a successful career in the City, given up his flat and his job and a regular salary to try to make something out of the old family home. While Colin’s university friends were out at wine bars, playing with their BlackBerrys, he was calculating crop yields. Admittedly, no one had held a gun to his head; it had all been his own choice, but from what I gathered, without that choice there wouldn’t have been much of a Selwick Hall for Jeremy to rent out.

Serena, for all her other neuroses, had her work at the gallery, a small but expensive flat in Notting Hill, and a fairly active social life in London.

What did Colin have?

“It’s for the best, you’ll see,” Serena was saying, speaking too fast, her lashes blinking rapidly. “We’ll all share the money equally. You can use yours on the Hall.”

Colin was still a step behind. I was reminded of people stumbling out of the doctor’s office after those drops that dilate your eyes, squinting at everyday objects in an attempt to reconcile the distorted images to their regular forms.

“Then . . . you did know?” He sounded incredulous, as though he still didn’t entirely believe it.

I thought of all the times Colin had looked out for her, all the times he’d cut short our dates, all the times he’d seen her home, and I wanted to slap her. All she’d had to do was say no, that was all. Was that really so hard?

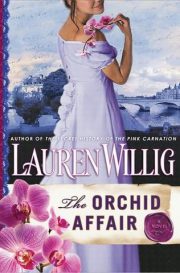

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.