“Somehow,” said André dryly, “I doubt Jeannette could have pulled that off in quite the same way.”

“Well,” said Laura. She tossed her brush aside and rose from the stool. “Let’s hope my acting skills prove equally good on the stage.”

“Nervous?” asked André.

“Nonsense,” said Laura. “All one has to do is act out a scenario. What can possibly be so hard about that?”

“Ruffiana? If you could, a little to the right?” called Pantaloon, for at least the third time in ten minutes. “You’re blocking Harlequin.”

Laura moved obediently to the right, knowing that it would be the left next time, or the middle the time after that. No matter where she was, it wasn’t where she was supposed to be.

Apparently, dissembling and performing weren’t quite the same skills after all. Leading a double life didn’t seem to have prepared her for the exigencies of the stage. Lying one’s way into someone’s household didn’t necessitate such skills as projecting one’s lines or remembering to cheat out towards the audience. Upstage, downstage . . . Laura’s head swam with it.

None of the others seemed to be having the same problem. André, it seemed, was a natural on the stage. She would have accused him of practicing on the sly but for the fact that he hadn’t known about the acting troupe until after she had. It must be his background in debate, Laura decided. Like Commedia dell’Arte, being a public representative was an art form that demanded thinking on one’s feet and speaking very, very loudly.

Being a governess didn’t provide quite the same training.

Excuses, excuses. No matter how she attempted to parse it, the result was the same: She was an unmitigated disaster on the stage. Even de Berry had done better than she. He, at least, remembered to address his lines downstage.

“Shall we begin the scene again?” suggested Pantaloon wearily.

“What makes him think the tenth time will make any difference?” murmured Rose to Leandro.

Leandro blushed and scuffed his feet, torn between his innate good nature and the attentions of his goddess.

“Is it time for supper yet?” Laura asked hopefully.

Harlequin checked his watch. “It’s four o’clock.”

Blast.

Pantaloon sighed and rose from his perch on an overturned log. “Again, I think. We must have something to perform when we reach Beauvais.”

Beauvais was to be their first stop, roughly a week hence. They were rehearsing in the open, in a clearing in a wooded copse. It had been deemed a good place to camp, largely due to the small pond nearby.

From Leandro, who did manage to string together complete sentences as long as Rose was out of eyeshot, Laura learned that they were taking something of a detour. Under normal circumstances, the troupe would have traveled by the major roads, stopping to give performances along the way, staying as many as three nights if the town were large enough and the take good. With so many new troupe members, Pantaloon had decreed it more prudent to take to the back roads, using the opportunity to put the new cast members through their paces. By avoiding the inns, they broke even. There was no revenue, but little in the way of cost.

It also meant they had no witnesses. There was no one to comment on the man with the strangely broken hand, the actor with the oddly aristocratic accent, or the two small children who just happened to have the same names as the small children of a wanted man.

According to Leandro, the decision had been Pantaloon’s. Pantaloon was, after all, the nominal head of the troupe. Laura had a fairly good idea who had first broached the plan.

Laura wondered how much the Pink Carnation was paying Cécile. Whatever it was, she deserved double.

Laura thought back over the rehearsal. Make that triple.

“From the beginning, then,” said Pantaloon. “Ruffiana, you have intercepted Harlequin, who is returning from a rendezvous with Columbine, who has given him a note from Inamorata to be delivered to Leandro. You want him to play go-between on your behalf with Il Capitano, but first you must feel him out to make sure he won’t betray you to your husband. Understood?”

“Perfectly,” said Laura. It wasn’t the scenario she had trouble with. She could summarize it perfectly well. It was acting it that was the problem.

Apparently, one couldn’t just walk up to Harlequin and say, “Hello, young messenger. Would you carry this letter for me?” No. One had to work around to it and make it sound natural. Preferably with sufficient double entendre to keep the audience amused, interspersed with a well-worn repertoire of physical gags.

André had been brilliantly comedic as Il Capitano, the blustering Spanish officer simultaneously attempting to seduce young Inamorata and repel the advances of her mother, Ruffiana. Even de Berry had been adequate as Leandro’s two-faced best friend, who pretends to aid in the courtship of Inamorata while secretly wooing her for himself, although Laura did wonder how much of that was acting and how much the prelude to an actual seduction.

They began the scene again. Harlequin strolled “onstage,” hands in his pockets, whistling a merry Mozart tune, only to be intercepted by Laura. She gave an exaggerated start of surprise. “You! You there!”

“I, Madame?” Harlequin waggled his eyebrows in a way that managed to be effortlessly comedic.

“Yes, you.” Blast. What next? Molière this was not. Next time she escaped from Paris, it was going to be with a classical theatre troupe, where one could simply memorize one’s lines. Memorization, she could do. “You have the look of a lackey. Can you carry a letter for me?”

“For a beautiful woman”—Harlequin made the word “beautiful” a joke in itself, in complicity with the imaginary audience—“there’s very little I can’t carry.”

“Er, good. Um. I have need of your skills. Your letter-carrying skills.”

Pantaloon dropped his head into his hands.

“Where did you say you performed again?” said Harlequin jokingly, dropping out of character.

“I’m sorry,” said Laura wretchedly. “I don’t know where my mind is today. I must have offended one of the muses.”

She meant to make a joke out of it, but it fell flat. The others exchanged significant looks.

“We’re all tired,” said André quickly. “After being based in Paris for so many months, none of us are used to this much travel anymore. It saps the creative energy.”

It hadn’t seemed to hurt his creative energy.

Laura mustered an unconvincing yawn. “Please forgive me,” she said. “I didn’t sleep much last night.”

“Didn’t you?” murmured Harlequin. He winked at André. “You’re a lucky man, Capitano.”

She hadn’t . . . Oops. Laura bit down on a quick negation. In any event, at least this furthered the pretense that they were married. She could cling to that small reassurance, at least.

It was a new and unsettling sentiment, feeling this incompetent. She didn’t like it, not at all. She might not be particularly talented or inspired, but she had always at least risen to the level of competence.

“We’ll have an early night tonight and resume again tomorrow,” said Cécile briskly. “Everyone has a bad day now and again.”

Laura trailed after her out of the clearing. One bad day, yes. But what happened when she failed again tomorrow?

How long before the other actors smelled a rat?

Chapter 27

“It shouldn’t be this hard,” Laura muttered. “It’s simply a matter of knowing what to say and where to stand. How hard can that be?”

“Very,” André said, propping himself up on one elbow.

He was sprawled comfortably across the pallet, waiting as his temporary wife prepared for bed. Since she didn’t appear willing to remove much in the way of clothing, this consisted solely of yanking her hair back into a braid that looked as though it were intended as much for punishment as convenience. André winced in sympathy for her scalp as she crossed one section with another.

A brief squall of rain had driven the troupe from their campfire early tonight. As Pantaloon had commented, not unkindly, it was perhaps for the best. If they were to perform in Beauvais on Saturday, they would have a great many miles to travel the next day and an even greater deal of work to accomplish.

Seated next to Laura, André had felt her flinch at the words. She knew they were intended for her.

Laura gave the knot at the bottom of her braid a final, vicious yank. “But you manage well enough. Better than well enough. You were quite good.”

André leaned back against the bunched-up pillows. “I’ve had more practice than you have. I participated in the odd amateur theatrical in my youth.”

More than a few, in fact. There had been a large garden behind Père Beniet’s house, with a terrace perfectly suited for balcony scenes.

They had been such innocent revels, those summer theatricals. They had all laughed a great deal—sometimes at Julie, who could never remember her lines; sometimes at Renaud, comrade in legal studies, who thought no play was complete without a duel and insisted on inserting them in the most unlikely places in the narrative.

Renaud had died long since, killed in the fighting in the Vendée during the war. He had never been meant to wield any weapon heavier than a law book.

The others, too, were gone, each in their own way. Julie, dead. Marie-Agnès, Julie’s cousin, married with three children in Brest. Their entire enchanted summer circle, scattered and gone.

“Don’t forget,” he added wryly, “I’ve spent the past few years playing at a pretense. There’s nothing like the threat of execution to improve one’s acting skills. You wouldn’t know that.”

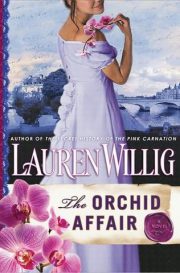

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.