The Pink Carnation gazed at the painting, her elegant profile serene. “Sometimes, among the bustle of town, it can be pleasant to lose yourself in a bit of greenery. It’s so peaceful among the trees. So quiet.” Without any change of inflection, she continued, “I often go walking in the Jardins du Luxembourg. I like to go in the morning, while the mist is still fresh on the ground. So refreshing, wouldn’t you agree?”

Without waiting for an answer, she turned away, flapping a hand in the direction of the American woman.

“Emma!” The American looked around, caught in the middle of haranguing Augustus Whittlesby. “Emma! Do come here and give me your opinion of this painting.”

She had been dismissed, Laura realized, neatly and decisively. Anyone watching would have seen Miss Wooliston making the minimum of polite conversation with the awkward odd woman out, and then, as any of them would, calling for reinforcements.

The American complied, cheerfully enough. Whittlesby looked distinctly relieved.

“You know I’m hopeless at painting,” the American said, squeezing her way in between Laura and the Pink Carnation.

Miss Wooliston rolled her eyes at her friend. “I’m not asking you to paint it, merely to critique it. Tell me if I’m about to waste my pin money.”

The American eyed the first easel without favor. “Please tell me you’re not planning to buy Caesar’s Last Stand.”

“No, not that one. The forest scene. It’s like a walk in the woods at ten in the morning.”

Emma examined it critically. “I would have said afternoon, but it’s so overcast it’s hard to tell. Wouldn’t you prefer something a little . . . brighter?”

“Really?” The Pink Carnation slid an arm through her friend’s, drawing her away, away from Laura. “I would have called it atmospheric, like something out of a novel by Mrs. Radcliffe.”

“Hmm.” The American was unimpressed. “Come see this one.”

Laura drifted to an easel at the other side of the room, staring without seeing. She had a vague impression of color, but she couldn’t have said with any authority exactly what it was she was looking at.

The Pink Carnation’s message had been clear enough. The Jardins du Luxembourg, tomorrow morning at ten. There must be something important in hand, something very important if the Pink Carnation was concerned enough to break protocol and speak to Laura herself.

“Laura, my dear.” She started as Daubier placed a fatherly hand on her shoulder and squeezed. There was reddish paint on his fingers, the marks that no amount of turpentine could scrub off. In Laura’s uneasy frame of mind, it looked uncomfortably like blood. “Has André abandoned you already?”

“He was more than generous with his time.” Laura forced herself into a lightness she didn’t feel. “And with his vol-au-vent.”

“I’ll say that much for André,” agreed Daubier. “He doesn’t stint on the buffet. So, my girl, what do you think of this lot?”

He gestured expansively at the easels lining the room.

Laura’s mouth settled into wry lines. With all the people asking her that this evening, she might as well hang out her shingle as an art critic. Everyone seemed so eager for her assessment.

She was spared answering by a disturbance at the doorway. Someone was forcing his way into the room, boots clomping against the time-dulled parquet floor. People scattered at his approach, like birds startled from their bread crumbs, hastily taking wing.

The crowd cleared, and Laura saw who it was. It was that man from the Ministry of Police, the one who had stopped them on the bridge. The one who had pretended to know her.

For an awful moment, she thought he was making for her, her subterfuge discovered, her death warrant signed. But his eyes passed right by her. He wasn’t on the trail of the Pink Carnation. Laura could see one last swish of her skirt as she strolled easily through the far door, her arm twined through that of her American friend, seemingly oblivious to the commotion being created, as if she were merely the society lady she pretended to be.

Laura’s relief turned to alarm as Delaroche stopped directly in front of Monsieur Daubier.

Everyone, including Laura, stepped back, giving the two men a wide berth. They stood alone in their circle of floor, people clustering around at a safe distance, like spectators at the Roman Coliseum.

“Antoine Daubier?”

“Yes?” Daubier’s expression was politely quizzical, but there was something beneath it that made Laura’s stomach twist.

She could hear his voice, from a very long way away, saying, Do you think he—

Whatever this was about, Daubier knew about it. He knew and he was bracing himself for the blow.

Delaroche seemed to grow taller. His sallow face blazed with triumph.

“Antoine Daubier, I arrest you in the name of the Ministry of Police.”

Chapter 17

André Jaouen pushed into the circle, breaking the spell.

“Not in my house,” said Jaouen, his eyes never leaving Delaroche’s. He spoke softly, but there was steel beneath. “Monsieur Daubier is a guest in my home. As are you. You overstep the bounds of hospitality, Monsieur Delaroche.”

“Monsieur Daubier is an enemy of the Republic.” It cut through the din of the room, slicing through conversations like the blade of the guillotine. “Do you deny it, Monsieur Daubier?”

Daubier tried for a jovial tone, but there was a gray tinge to his face. “My daubs are not so very unfortunate as that, Monsieur Delaroche. Surely the odd artistic failure is not to be accounted treason.”

“It isn’t your dabblings in oil which concern the Ministry of Police, Monsieur Daubier. As you well know.”

To the other spectators, it might have seemed like something out of the Comédie-Française, all innuendo and allusion. But Laura felt apprehension grip her as Daubier shook his head, his face gray. This wasn’t theatre, not to him. “No, I’m afraid I don’t.”

Delaroche leaned forward. “You deny you have been conspiring against the First Consul?”

Daubier mustered an attempt at a smile. “I would be a fool not to deny it, even if such a thing were true. Which it isn’t. The First Consul has commissioned a portrait from me. I would hardly go about conspiring against my own patron.”

Daubier looked about, as if looking for support. None came. The people around him hastily averted their eyes, wary of contamination by association.

Jaouen finally stepped in. “There has been some mistake,” he said flatly.

That was all? There has been some mistake? Laura regarded him with sudden wariness. Surely, for a man he called friend, he could muster some better defense than that.

Unless, of course, he didn’t intend to. Unless he had never intended to.

It was his party, his guests. Was it also his arrest?

“There has been a mistake,” agreed Delaroche. He turned to Monsieur Daubier, whose form looked oddly shrunken in his gaudy clothes, as if the bombast had been knocked out of him. “The mistake was yours, Monsieur Daubier, in underestimating the reach of the Republic.”

“I—” Monsieur Daubier shook his shaggy head. “I do not understand.”

Delaroche leaned forward. The crowd leaned in, straining to hear. “I think you do understand, Monsieur Daubier. I think you understand very well.”

Jaouen looked at Delaroche and said, in bored tones, “Must this scene be performed to an audience, Gaston? If you will both come with me—”

“The only place Monsieur Daubier is going,” said Delaroche, “is to the Temple.”

The air grew chill.

“I was going to suggest my study,” said Jaouen mildly. “It is nearer, and the refreshments are better. I am a little short on racks and thumbscrews at the moment, but I’m sure you can make do.”

A nervous titter ran around the crowd.

“Do you mock my work?”

Jaouen raised his brows. “Far from it, Gaston. I admire your artistry. But we have many artists here tonight, all eager to show their works, and this . . . display is impeding their efforts. I suggest,” he added, raising his voice so that it carried throughout the room, “that we all go back to enjoying the arts. Monsieur Whittlesby has a new poem for us, I believe?”

“In twenty-five cantos!” called out Whittlesby.

Someone groaned.

It had been the right thing to say. The nervous tension gripping the room broke. People turned to their neighbors; rustled in their reticules; drifted over to the refreshment tables. As far as they were concerned, the show was over.

Something dark and nasty passed across Delaroche’s face, and Laura’s stomach sank again. This wasn’t over yet. The audience might have gone, but Delaroche was determined in his purpose, all the more determined now for having been publicly balked.

Jaouen turned to Delaroche. “My study?”

For a moment, Laura thought Delaroche meant to agree. Then Delaroche clapped his hands, once, sharply. From behind the thinning ranks of the spectators appeared two men in official costume. Like Delaroche, they were booted and spurred. There was no mistaking them for guests. They moved purposefully towards Daubier, who looked at them with dawning alarm.

Delaroche pointed a bony finger at Daubier. “Bind him.”

“This,” Jaouen said, “is a most marked breach of hospitality. Professional courtesy only goes so far, Gaston. Drop him,” he said sharply to the guards.

The guards looked uncertainly from Jaouen to Delaroche and back again.

“The ropes,” said Delaroche. “Now. This man is dangerous.”

Even the guards looked askance at that. Daubier had never looked less dangerous. He looked like what he was. An overweight man well past the prime of his life with unkempt hair, a too-bright waistcoat, and paint on his fingers.

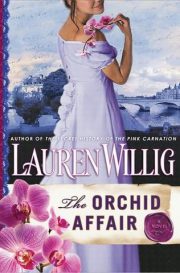

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.