Some things hadn’t changed. The Café de la Régence was crowded with dedicated chess players. As Laura walked past, the crowd shifted and she caught sight of a man standing just outside, checking his pocket watch. He had left his hat off, and the sun glinted bronze off his short brown hair. He was turned slightly away from her. She could see the cowlick in back, so inappropriately boyish for a member of the Ministry of Police.

The crowd jostled Laura sideways, towards Jaouen. He looked up from his watch. Laura raised her hand in greeting.

“Monsieur Jaouen!” she called breathlessly.

She hadn’t seen him since their run-in in the storage room. His comings and goings had been at odd hours, although she had more than once heard movements in the nursery at night. The first time, she had assumed it was an intruder. Taking up her poker, she had inched open her door and crept out into the schoolroom, only to find Jaouen, still cloaked and spurred, silhouetted in the open nursery door, watching his children sleep. Lowering her weapon, Laura had slipped back into her room, easing the door shut behind her. Some moments weren’t meant to be disturbed.

Jaouen turned at the sound of her voice, squinting into the sun. Already regretting the impulse, Laura did the only thing she could do. She raised her hand in greeting. “Good afternoon, sir—oooph!”

Her greeting turned to a grunt as the man behind her bumped into her, sending her careening forward. She rocketed into her employer, landing with a thump against his chest. Or perhaps that thump was the parcel hitting the ground. Laura didn’t know, because she couldn’t see. Her bonnet was knocked sideways over her eyes, the brim mashed somewhere between her face and Jaouen’s shoulder.

Jaouen’s arms closed around her, his body breaking her fall. The wool of his coat was rough beneath her cheek, warm from the sun and his skin.

Laura heard Jaouen’s voice, somewhere just above her left ear, amused, if rather breathless. “A simple ‘hello’ would have sufficed.”

She could feel the vibration in his chest as he spoke, pressed together as they were through all their layers of fabric. It was the sort of position in which no good governess allowed herself to be put, not even in the street, not even in the middle of the day. It was too intimate, too undignified, too . . . Too.

Laura wriggled. “You can let me go now,” she said in muffled tones.

Jaouen released her to arm’s length, his hands lingering for a moment on her upper arms, steadying her. “A unique way of saying good day, Mademoiselle Griscogne. What do you do for farewell?”

Laura could feel the press of his fingers, even after he let go. “I am so sorry. I didn’t mean to . . . I’m afraid I lost my balance.”

“One often does after being pushed.” Jaouen moved to block her from the bustle of the street, using his only body as a shield. “Think nothing of it. I’m simply glad you fell onto me instead of the window. The patrons of the café might not have been amused to find you as an additional pawn.”

Laura’s bonnet brim stuck up at an odd angle, knocked askew by Jaouen’s shoulder. She tugged at it ineffectually. “It was my own fault for stopping in the middle of the street. I should have known better than to . . . Oh, bother. My parcel!”

“You mean the large, heavy thing that assaulted my foot?” Jaouen leaned over to retrieve the package. It had been wrapped in brown paper, but none too carefully. The string had snapped when the parcel had fallen. “More books, Mademoiselle Griscogne?”

“It would be very difficult to teach without them,” she said quickly, reaching for the volume.

Jaouen held on to it. “Buying volumes for the children on your half day, Mademoiselle Griscogne? I should have thought you would have been set on frivolity.”

“Oh, certainly. I might dip deep into dissipation with a walk around the park, or even a daring visit to a public concert.” Laura made one last attempt to wrench the brim of her bonnet into place. It stubbornly refused to bend. “Since I cannot take the children with me to the bookshop, I must go without them. On my half day.”

“Touché.” Jaouen tipped his hat to her. “A hit.”

Jostled by someone in the crowd, Laura did a little half-step to avoid stumbling into him again. “I would never think of sparring with my employer. It would be decidedly improper.”

Jaouen raised an eyebrow at her. It was amazing how much sarcasm could be packed into one little arc of hair. “If this is your way of being peaceable, I would hate for us to be at war.”

Little did he know. “Would I bite the hand that feeds me?”

“My guess? Yes.” Something in the way he said it made Laura’s cheeks heat. Jaouen cleared his throat, dropping his eyes to the book in his hands. “What’s this, then? What tales are you telling my children?”

Laura resisted the urge to snatch it from his hands as her employer flipped at random through the pages. Each page contained a crude woodcut illustration, with verses in Latin and French beneath.

“These look familiar,” said Jaouen, pausing at the image of a wolf flipping his tail at a cluster of grapes dangling tantalizingly just out of reach. “Aesop’s Fables?”

“It makes an easier introduction to Latin than Caesar’s Wars. The children learn faster when presented with something familiar.”

Jaouen flipped another page. “I wish my Latin master had been half so accommodating.”

Laura craned to see over the edge of the book. It was a crow this time, peering into the water. The Carnation wouldn’t have left anything incriminating between the pages. She hoped. “The nature of the subject matter does not render the instruction any less rigorous, I assure you.”

“I would never suspect you of being anything less than rigorous. I shouldn’t want you to call me out for questioning your pedagogy.”

“Are you afraid I would challenge you to Latin verses at ten paces?”

“It’s the sums at dawn to which I object.”

There was something oddly intimate about the image. Dawn. Disordered hair and tousled sheets, warm skin and dented pillows.

Laura pulled herself together. She was a governess, for heaven’s sake. She wasn’t supposed to think of such things. “The fables do provide excellent moral lessons.”

Jaouen’s fingers moved busily through the pages. “Do they? Here’s one for you.” Looking at the Latin below, Jaouen read aloud, “‘Multi sub vestimentis ovium lupina faciunt opera.’”

He read it as easily as he read French. Whoever had taught him classics had taught him well. Laura thought she knew now to whom the Seneca, Virgil, and Plutarch had belonged.

Peering over his shoulder, Laura saw a woodcut of a wolf with a sheep’s fleece draped half over his lupine shoulders. The wolf looked decidedly shifty.

“‘Many do the work of wolves beneath the clothing of sheep,’” Laura translated for him.

Jaouen closed the book, none too gently. “A useful lesson. Especially here in Paris.”

Laura accepted the book as he held it out to her. “Why Paris especially?” she asked. “Surely, no one city has the monopoly on deception.”

“Have you traveled so widely, Mademoiselle Griscogne?”

“I have served in a great number of households,” she said circumspectly. That much was true.

From down the thoroughfare, a rich voice bellowed, “Jaouen!”

Pedestrians gave way as a man approached, a massive figure in a coat of such garish crimson and gold that it hurt the eyes to look at it. His waistcoat, protruding below, was patterned in wide blue and white stripes, adorned with broad bronze buttons that served barely to contain his immense girth. A shock of silver hair framed his face like a lion’s mane, sticking out from under the high-crowned hat jammed down on his head. He swung a bronze-tipped walking stick in greeting as he came towards them, deploying it like a bandleader’s baton.

No. Oh no, no, no.

It couldn’t be. The last time Laura had seen him, he had been slimmer. Not slim—he had never been slim—but he had been tall enough to carry the layer of fat well. His hair had still been its natural brown, streaked with the odd bit of gray, and usually held back by a bit of ribbon or string or whatever else he had happened to find in his studio. Even then, though, he had possessed a taste for garish colors, for waistcoats in all the shades he would never stoop to place on his palette.

Laura’s mother used to laughingly accuse him of venting all his gaudiness on his person and reserving none for his paintings, which were meticulously detailed and rigorously controlled, in a palette that ranged from beige to brown. “With the odd bit of blue,” he would say, and Laura’s mother would smile and touch his cheek with the back of his hand. “Caro, caro,” she would say with a sigh, and Daubier would laugh his deep belly laugh while Laura’s father propped his feet up on a stool, wine balanced on his flat stomach, lost in his own contemplations.

Sunlight flashed off the knob of his cane. Laura blinked, forcing her dazzled brain to clear. There was no point in denial or escape, he was ten paces away, five, moving fast. Painter, bon vivant, loving friend. He had given her piggyback rides, her hands tangled in his hair, dipping her to make her squeal.

He didn’t see her at first. His goal was Jaouen. And why, thought Laura, with an ache she hadn’t expected to feel, would he notice the drab thing in gray standing at Jaouen’s side? Unlike Daubier, there was nothing to link her to the thing she once had been. She had changed out of all recognition.

Antoine Daubier fell on Laura’s employer with an embrace as exuberant as his clothing, dealing Jaouen a smacking kiss on either cheek.

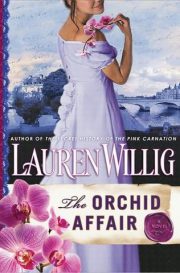

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.