“Well, anyway,” I said, brushing that aside, “the Pink Carnation came back home for Christmas in 1803. Thanks to your archives, I have full documentation on that. While she was there, she solicited the services of a graduate of the Selwick spy school, a Miss Grey.”

“A good name for an agent,” commented Colin. He should know; not only was he descended from spies, he was writing a novel about them—although his novel, or so he claimed, was more of the James Bond variety, complete with extraneous gadgetry and hot and cold running women.

“They dubbed her the Silver Orchid. I suppose they couldn’t very well go around referring to her as Miss Grey in correspondence.”

“Why not just 24601?”

“You don’t think Victor Hugo would have objected?”

“He wasn’t born yet,” Colin pointed out.

“Details, details.”

Colin raised a brow. “And you, a historian.”

“Even historians go on”—the shuttle came to an abrupt halt, sending me lurching forward—“holiday,” I finished breathlessly.

Okay, I got it; the shuttle driver wasn’t a fan of academic history. Or of Hugo.

“Minerve!” he called back. With a long drag on his cigarette, he settled comfortably back into his seat, pausing only to exchange obscenities with a passing driver who had taken umbrage with his stopping in the middle of the street.

Colin went to check us in while I loafed around the inevitable leaflet rack. There were advertisements for various museums and attractions, some of which I had heard, others more obscure.

My attention was caught by one for a special exhibition at a museum I had never heard of. It was a single sheet, on glossy paper, with a diagonal band across the middle that read, in bold letters, Artistes en 1789: Marguerite Gérard et Julie Beniet. It was a little early for my time period, but close enough to pique my interest.

A large key dangled in front of my nose. “All set,” said Colin. “Ready?”

“Ready.” I shoved the leaflet into my pocket and took the key from him. As the one with a large shoulder bag, I automatically assumed the role of Keeper of Movable Objects, including, but not limited to, keys, tissues, cough drops, and airline tickets.

The elevator was a tiny thing, barely large enough for the two of us to squeeze in together, our luggage jammed in at our feet and my shoulder bag wedged between us like a modern chastity belt. The wooden tag attached to the key, worn smooth with time and use, read 403. Room 403 turned out to be all the way in the corner. After two tries, during which I accidentally relocked the door while Colin tried to reach around me to help and managed to bang an elbow on the door frame, the lock finally gave and we both all but fell into the room.

It was certainly cute. There was pink-striped paper on the walls, pink fleurs-de-lis ringing the green carpet, and a mural on the ceiling, featuring an idyllic image of fluffy white clouds, blue sky, and green foliage, with a few birds winging their way peacefully along. It was also about three feet square, the entire center of the room taken up by a double bed sporting a pink quilt and four suspiciously flat pillows. The ceiling sloped down at an acute angle behind the bed. On one wall, long windows opened out onto a view of an air shaft. On the other side, a narrow sofa covered in a pink and green print stretched across one wall. A desk had been jammed in the corner across from the door, with just enough space for the door to clear.

The room looked absurdly small—and absurdly pink—with Colin standing in the middle of it. His big leather folding bag took up the better part of the bed.

“It’s cozy,” I said, dumping my own overnight bag on the sofa. “Cute.”

My bag was about an eighth the size of Colin’s. Fortunately, cocktail dresses pack small. So does the aspirational lingerie that one buys in the hopes of things like romantic weekends in Paris, that then generally sits in the back of the drawer, gently yellowing.

That, I had to admit, had been a big part of the draw of this weekend’s Paris jaunt, the chance to finally take out the That Weekend lingerie. I might not have the guts to wear it, but at least it was getting an outing.

Colin pointed at the painting on the ceiling. “Nice touch. Ouch.” He’d banged his head on the slope.

Wincing in sympathy, I put a hand to his temple, sliding my fingers through his hair. It was beginning to get long on top, like the floppy-haired teen idols of my 1980s youth. “There?”

Colin angled his head for better access. “You can keep rubbing,” he said hopefully. “A little to the left. . . .”

“I think you’ll live.” I patted him briskly on the shoulder and stepped back. “All right, BooBoo, let’s go.”

“BooBoo?” Colin looked at me quizzically as I jettisoned my in-flight reading from my bag. Because everyone needs three heavy research tomes and two novels for a forty-minute flight.

“You know. As in ‘Sit, BooBoo, sit.’” Every now and then I forget that we’re divided by a common language. I’d never felt quite so glaringly American until I started dating an Englishman. I decided to leave off the “good dog” bit. Even the most laid-back of boyfriends might take that the wrong way. “It was a commercial.”

Colin decided to let it go. He twisted the door handle, conducting an elaborate shuffle in order to open the door without trapping himself behind it or impaling himself on the side of the desk. He managed it, but only just. “Shall we get a coffee before I lose you to the archives?”

“I’d love a coffee.” I scooped up the key and gestured to him to move along so I could lock up. There wasn’t room for both of us. “And maybe one of those marzipan pigs.”

“Marzipan what?”

“Pigs.” I hoisted my bag up on my shoulder and followed him back along the hall to the elevator, walking a little bit behind, since there wasn’t room for us to go two abreast. “They were sort of a thing for me and—well, they were sort of a thing last time I was here.”

I squeezed myself into the elevator next to him. No need to explain that the last time I had been in Paris had been with my ex, Grant. He’d been speaking at an academic conference and I had tagged along. A lot of Grant’s time had been devoted to departmental schmoozing, which was only fair, considering that his department had been paying his tab, but I had managed to kidnap him for coffee and cake in between panels.

I had been delighted by the marzipan-coated pigs, Grant rather less so. He had been even less delighted when the pig attempted to carry on a conversation with him. Not that it was anything particularly deep. It had been more of the “Hello, Mr. Piven. Are you planning to eat me?” variety. Grant had been terrified that one of his colleagues would see him in flagrante pigilicto . Not very good for one’s image as a mature and responsible member of the faculty of the Harvard gov department.

That was what he got, I’d teased him, for dating a grad student.

Not one of his grad students, he’d hastily specified. Dating one’s own grad students was a no-no, punishable by expulsion. I was in another department; I was fair game.

So, apparently, were underage art historians.

But that had all been a long time ago. Two years ago, to be precise. It had been more than a year now since the breakup, two years since we had been in Paris together. This Paris would be a different city; my city with Colin, not with Grant.

The elevator decanted us into the lobby and we wiggled our way out, the strap of my bag snagging on Colin’s coat.

“Marzipan pigs, eh?” said Colin, skeptical, but game, and I liked him even more for it, liked him so much that it made my chest hurt.

“You’ll see.” I threaded my arm through his. “The big question is, tail first or head first?”

“What do you usually do?” he asked.

“I generally start with the tail and work my way up.”

“Prolonging the agony? Bloodthirsty woman.” Colin sounded like he rather approved. He nodded towards the desk. “Shall we see if Serena’s in yet?”

“We can get her a pig too,” I said cheerfully. Serena needed fattening up. They say a camel can’t fit through the eye of a needle, but Serena probably could. She was at the point of thin that crosses over from elegant to gaunt. And, no, that wasn’t just sour grapes speaking.

I smiled ingratiatingly at the receptionist, who couldn’t have cared less.

“Est-ce que une Serena Selwick est ici?” I asked in my very ungrammatical sixth-grade French. I can read the stuff; just don’t ask me to speak it.

The receptionist was not impressed. She checked the book. “Selwick . . . 403?”

“Um, no,” I said. “I mean, non. Nous sommes dans 403. Me and him. Nous cherchons l’autre Selwick. Serena?”

“Oui.” The woman seemed unfazed. She poked a manicured nail at the book. “Selwick. 403.”

This was getting a little frustrating. “Mais où est l’autre Selwick? Une autre Selwick? There should be another reservation.”

Now it was her turn to look confused. From the look on her face, she was thinking, Americans. Why do I always get the Americans?

Colin stepped in. “My sister is also staying here,” he said in accented but perfectly grammatical French. “Which room is she in?”

“Room 403,” repeated the woman in the same language, frowning at him, although not as she had frowned at me. This was confusion, not annoyance. “The entire party is in 403. It is a room for three.”

“What?” I yelped. Like I said, I can’t speak it, but I can understand it. Room for three came across loud and clear.

Turning to me, she switched to English. “How you say? A . . . three-person,” she said helpfully.

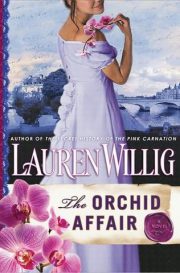

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.