The Pink Carnation managed to look their way without ever looking at Laura, as though Laura were no more an object to be remarked than the table used as a counter or the smoke leaching from the brazier. A servant. Invisible.

It seemed like a good time to take her leave.

“Come along, come along,” murmured Laura, wedging the four fat books under one arm and shooing Pierre-André ahead of her. “Gabrielle! You don’t want to keep these nice ladies from their shopping.”

With a protective eye on her book, which was currently bundled with the others under Laura’s arm, Gabrielle fell into step.

Laura pushed with her shoulder against the door, holding it for the children to precede her.

As the door slammed behind them, she heard the Pink Carnation earnestly asking the stepdaughter of Bonaparte, “What did you think of Madame de Staël’s latest novel?”

“Can I have purple feathers?” Pierre-André’s shrill voice drilled into Laura’s ears.

“Maybe,” said Laura, shifting to readjust the clumsy pile of books under her arm. “What would you use them for?”

“Flying,” he said, as though it were perfectly obvious.

“May I have my book?” interrupted Gabrielle.

“When we get back to the house,” Laura said. “I don’t want to undo the package while we’re walking.” She wondered if there would be another note hidden among the pages of the botanical treatise. She doubted it. The Pink Carnation’s message had been clear enough.

Gabrielle crunched loudly down on a thin patch of ice. “I don’t see why we couldn’t take the carriage,” she muttered.

“Because walking is good for you,” said Laura bracingly. And because she didn’t want the coachman to have a record of where they had gone. While there was no reason for Jaouen to suspect anything amiss about the bookshop, there was also no reason to lead him straight to it.

The road was busier than it had been when they had left, with people making their way home from offices and shops. The early winter dusk was already beginning to fall, tinting everything it touched with gray and lending a curious appearance of insubstantiality to the landscape as they passed, as though the stucco walls of the narrow houses were made of fog. The high walls cast strange shadows into the street, creating wells of darkness in which the shapes of passing people took on an ominous aspect. It might have been the twilight or the children’s flagging energy, but the walk back along the alleys of St. Michel seemed far longer than the walk there.

It was with relief that Laura emerged onto the Seine, holding one of her charges by each hand. Gabrielle had protested the gesture, but Laura didn’t want to risk losing her in the growing dark. The lights from the houses on the Île de la Cité reflected in the river, creating shimmering patterns in the water.

“Stay to the side,” warned Laura, as carriages rumbled past. “You don’t want to get squished.”

“Don’t want to walk anymore,” whined Pierre-André, burying his face in Laura’s waist. Laura had to execute a hasty double-step to keep from tripping over him. “Tired.”

“Just a little bit longer,” she promised. “We’re almost home.”

“That’s not home.” If she had been a few years younger, Gabrielle would have probably been burying her face in Laura’s waist too. Instead, she tugged her hand free and folded her arms tightly across her chest. “It’s just where we live.”

Laura knew what that felt like.

When was the last time she’d had a place that felt like home? Not since she was sixteen. Her parents had never kept a traditional home; they had moved from place to place as her parents’ whims and fortunes took them. Nonetheless, by some strange alchemy of affection, her parents—her excessive, flamboyant parents—had managed to make the series of borrowed rooms and lodging houses feel like home. Wherever they had been, that was where home was. And when they were gone. . . well, here she was.

“Home is where the people you love are,” Laura said, surprising both herself and Gabrielle.

Gabrielle gave her a look. Laura couldn’t blame her. At that age, she wouldn’t have understood it either.

“Home was in Nantes,” Gabrielle said. It was evident that she thought Laura very dim not to understand that.

“Will you carry me?” demanded Pierre-André. “My feet hurt.”

Laura herded the children towards the railing as a carriage drew alongside them, a little out of the ordinary stream of traffic. Instead of progressing, it slowed to a stop, despite the angry cries of the wagon owner behind it.

A man leaned out of the window, ignoring the various speculations on his ancestry being offered by the man behind him. He wore a tall black hat with a broad brim. The material had a threadbare sheen to it in the light of the carriage lamps. “Mademoiselle!” the man in the carriage called.

Laura put a hand on each of the children’s backs and hurried them forward.

“Mademoiselle Jaouen!”

Gabrielle stopped and turned, leaving Laura tugging futilely at the back of her coat. The carriage glided smoothly along beside them. It was a narrow, black conveyance, designed to hold only one passenger, or two at most. “It is Mademoiselle Jaouen, is it not?”

Laura took a tighter grip on the back of Gabrielle’s coat. “The children are not permitted to speak to strangers. Good day, Monsieur.”

“But I am no stranger. I am a colleague of their father’s.” The man leaned farther out the window, arranging his thin features into what he clearly believed to be an ingratiating smile. “And this young man must be Pierre-André.”

Pierre-André slunk back against Laura’s side and buried his face in her pelisse.

“The children are very tired,” said Laura, by way of explanation and apology. “I must get them home.”

The gentleman’s smile broadened. It reminded Laura of nothing so much as wolves in fairy stories. It was not a pleasing effect. “Allow me to assist you. I have the carriage at my disposal.”

Perhaps it was the teeth, but Laura found herself ill-inclined to take him up on the offer. “And very little room in it. We would not want to impose.”

The man held out a hand. “No imposition. Not when the children of a colleague are concerned.”

Something about the way he said “colleague” sent Laura’s hackles up. She pushed the children ahead, forcing them to move. “No need, sir. The walk will do the children good.”

Gabrielle sent her a decidedly baleful look.

“Feet hurt,” whined Pierre-André.

The man settled back in his seat, contemplating the mutinous children with an appraising air that made Laura think of a chef sizing up a joint. Perhaps not for this meal, but later.

“As you will, Madame,” he said. “But do be sure to give my regards to Monsieur Jaouen.”

“Who shall I say sends them?”

The man bared his yellowing teeth in a facsimile of a smile. “Delaroche. Gaston Delaroche.”

Chapter 5

It was with a heavy tread and weary heart that André returned to the Hôtel de Bac.

It was twilight again, twilight to twilight, one day bleeding into the other. A candle sat unlit on the table by the door. Blundering in the vast darkness of the hall, André found the flint and lit the candle, bringing the area around him into a semblance of visibility. In the grand, high-ceilinged chamber, the single flame seemed to emphasize the darkness rather than combat it.

He had the notes from Querelle’s interrogation with him. There was still a full night’s work ahead of him, turning fifty pages of disjointed testimony into reports of varying sizes and shapes: a discrete paragraph for the ledgers of the Prefecture, a one-page summary for the First Consul’s bulletin, and a more comprehensive account for Fouché’s private use, all to be delivered by the following morning. Memory presented him with Querelle’s face, skull-like in the candlelight, the skin sagging over the bones as he uttered the words that would condemn his comrades to a like cell in a like prison, and all their hopes with it.

This wasn’t what they had fought for, he and Julie.

André took the candle with him, using it to light his way to the room he had appropriated as a study.

There was a crayon drawing of Gabrielle and Pierre-André propped over the mantelpiece, the only item of personal significance that André had brought with him from Nantes to Paris all those years ago. In it, Gabrielle was a curly-haired five, Pierre-André a round-cheeked infant.

It was the last work Julie had done before she died.

Perhaps she was the lucky one, Julie, not to have seen how it all turned out, all their brave dreams of a world reborn. How joyously they had donned the Revolutionary cockade, seizing the chance for all their philosophies to be made flesh. Ancient injustice was to be banished, feudal dues abolished, the antiquated system that pitted noble against commoner erased. The Age of Reason had at last arrived, and they were its heralds.

André had attended the National Convention as one of the Nantes delegation, raising his voice against the entrenched evils of privilege and power, while Julie put her arguments into paint, creating bold historical scenes, mostly drawn from Ancient Rome, all depicting the triumph of Republican virtue over aristocratic sloth. Her Mother of the Gracchi had been all the rage, eclipsing even David’s Oath of the Horatii in its depiction of the sacrifices for one’s country incumbent upon a good citizen.

But not these sorts of sacrifices. Nor the ones that had been demanded by the guillotine in the name of public safety. That wasn’t the sort of world he and Julie had so optimistically planned to bequeath to their children.

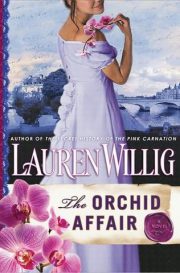

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.