Well, then, Laura told herself, keeping a grip on a squirming Pierre-André, the worst that would happen would be that they would have bought a book appropriate for a five-year-old.

The shopkeeper held up a book, squinted at it, clicked his tongue a few times more, and returned it to the pile, repeating this process before emerging triumphant with a large, ornately bound volume.

“You might want to try this,” he suggested.

No, no, no. Laura wanted to stamp in impatience. That wasn’t the right phrase. If he were her contact, he was supposed to say, “I usually recommend this for a child of seven,” or eight or nine, with the number representing the page on which she would find the key word that would then be used to decode the message.

“Oh?” said Laura. “What is it?”

Whatever it was, she hoped Pierre-André liked it, because it obviously wasn’t going to serve any other purpose.

Placing the book flat on the counter, the shopkeeper spread it open to reveal a delicately tinted engraving of a flower.

It was an orchid.

Chapter 4

It wasn’t silver. There was no such thing as a silver orchid. But it didn’t need to be. Laura knew exactly what it meant.

A thrill of excitement buzzed through her, heady as the champagne she dimly remembered drinking back in her pre-governess days.

“It’s perfect,” she said, and meant it. There would be no need for a page indication this time. She knew what her key word would be. “Silver.” In one fell swoop, the Carnation’s contact had confirmed his status and given her the code for the next message. “Natural history, is it?”

“Many young gentlemen these days are taking up botanical pursuits,” said the shopkeeper blandly.

“Young ladies, too,” Laura said, feeling positively arch.

“So I have been told,” said the shopkeeper, with something that wasn’t quite a smile. “Some may find it unconventional, but I hear that they take to it quite well.”

Laura felt an unaccustomed urge to grin. It was all she could do not to grab the shopkeeper by the hand and shake it, babbling, haven’t we done well? Aren’t we clever?

Instead, she nodded crisply, tapping a gloved finger against the open page of the book. “It will be good drawing practice for my pupils. We’ll take it.”

Without betraying any emotion, the shopkeeper closed the cover, concealing the orchid beneath a nondescript façade of blue leather. “Will there be anything more?”

“I will also need an introductory Latin text,” said Laura. That wasn’t part of the code, but, while she was teaching, she might as well teach. It would be hard to explain her continued presence in Jaouen’s household otherwise. “Do you have the Orbis Sensualium Pictus?”

“The—?” The shopkeeper paused to allow her to fill in the title.

It was a book she had often used to teach Latin before, especially to younger children. Brightly colored pictures were paired with the corresponding Latin and English translation.

“The Orbis Sensual—” Laura ground to a halt as she realized her blunder.

The second language after the Latin in the Orbis Sensualium wasn’t French. It was English.

She had used the Orbis Sensualium Pictus to teach English children in England. How could that not have occurred to her? That was certainly one way to get herself caught in a hurry; go about asking for English books in a French bookshop. She might as well emblazon “SPY” on her forehead. In capital letters. In English. With a Latin translation underneath.

Or she could just bang her head against the counter and wish she had never got out of bed that morning.

Laura glanced guiltily over her shoulder, but the only other person in the shop was the poet, who was, mercifully, too absorbed in poetic reflection to pay any attention to her faux pas.

“Never mind,” she muttered, and affected a cough to cover her confusion. She would have to be wary of slips like that. After sixteen years, she had become far more English than she had realized. So much for doing so well. Pride goeth, and all those other gloomy adages. She would have to be more careful in the future. “Er, do you have any picture books with Latin translations for children?”

Why hadn’t she just asked that in the first place? That was what she got for trying to show off.

“I can see about finding something like that for you,” the bookseller offered dubiously, “But it might take some time. We did have a copy of Aesop’s Fables in a Latin translation. I could have that for you next week.”

“Do you think it would be appropriate for a child of nine?”

“It very well could be,” agreed the shopkeeper. His slow nod of approval made Laura feel marginally less like an idiot. Whatever message the Carnation next wanted to convey would be found on page nine of Aesop’s Fables, corresponding to the code word “silver.”

“That would be very good of you,” said Laura, just as the door opened again with a tinkle of chimes and a blast of cold air.

Three women breezed into the store. Two were obviously ladies of fashion; the third, older by several years, was dressed with puritanical severity except for the truly alarming purple plumes that sprouted from her bonnet like a molting tropical bird. Laura sincerely doubted that any bird, even in the tropics, had ever dared to show itself among the avian haut monde in plumage of that shade.

Laura saw Gabrielle taking in the details of the ladies’ costumes with hungry eyes. With a twinge, Laura remembered what it was to be nine and plain, with that horrible awareness that one didn’t, somehow, look quite right. The child’s clothes were sturdy and well made, but they could not, under any circumstances, be termed anything other than provincial. Laura’s problem hadn’t been quite the same—she had, if anything, always been dressed in far too mature a style for her age—but she could well remember that anxious desire to look just like everyone else, and the squirming humiliation of knowing she didn’t.

She would have to speak to Jaouen about a new dress for his daughter. If books wouldn’t win Gabrielle over, perhaps pretty clothing might. And it would give her an excellent excuse to seek out her employer.

The poet’s sleeves expanded to hitherto unimaginable width as he flung his arms high in the air. Gabrielle hastily retreated back against a stack of books.

“My muse!” he cried, gesturing grandly at one of the ladies, who was magnificently turned out in a tight-sleeved, high-waisted sky blue pelisse finished in fur trim. She wore a bonnet with a silk-lined brim that shadowed her face, although not enough to curtain her from the eyes of her admirer. “Well met by midday, fair Miss Wooliston!”

Laura had to juggle to keep her grip on her book. Fortunately, no one was looking at her. All attention was on the lady in sky blue, the poet’s muse.

Or, as Laura knew her, the Pink Carnation.

Laura felt a tug on her arm. “What’s a muse?” demanded Pierre-André, in a whisper like a foghorn.

“Ah, the muse!” mused the poet, striking a pose like Jove about to throw thunderbolt. “The muse, my dear poppet, is a thing of glory, a flame of fire, a blazing comet of divine inspiration! In short—she!” He wafted his sleeve in the direction of the Pink Carnation.

The pretty lady didn’t appear to be on fire, but Pierre-André prudently backed up against Laura’s side in case she should blaze into divine inspiration and catch them all up in the conflagration.

Undaunted, the poet was courting artistic immolation. “I have just, this very morning, finished my latest ode to your sublime, um—”

“Sublimity?” suggested the Pink Carnation.

Gabrielle’s eyes were like saucers and Pierre-André was tugging at Laura’s arm again, hissing, “What’s sublimmy? And can I have a shirt like that? Can I? Can I?”

Turning back to the shopkeeper, Laura said hastily, “The Greek myths in the front. We would also like a copy of that. If you are a good boy,” she added to Pierre-André, “I’ll read you about Hercules and the snakes later. You’ll like the snakes.”

With a nod, the shopkeeper set off to the front to fetch the book.

Behind her, the poet was in full spate, fluttering his sleeves at Miss Wooliston in a bizarre sort of mating ritual. “Sublimity is too limiting a term to encompass the range of my regard for so rarefied a creature as thou. Which is why, instead of one word, I offer you five cantos.”

From somewhere in the vicinity of his left sleeve, the poet made good his word by producing a very thick roll of paper, beautifully tied with a pink silk ribbon.

“The pink,” he added helpfully, “represents love hopeful. I discuss that at some length in the fourth canto.”

Miss Wooliston eyed the thick roll of paper with comic apprehension. “You flatter me. Again.”

Her friend, a fair-haired woman whose claims to beauty were marred by the length of her nose, came to her rescue, “When will you immortalize me, Monsieur Whittlesby?”

The poet swept an elaborate bow that set all his ruffles fluttering. “You, Madame Bonaparte, have no need of my humble pen to make you immortal.”

Bonaparte. He had said Bonaparte, hadn’t he? If there had been anything in Laura’s mouth, she would have choked on it.

This Mme. Bonaparte was too young to be the First Consul’s wife, so it was presumably his stepdaughter, Hortense, made doubly a Bonaparte through her marriage to the First Consul’s younger brother.

That was a lot of Bonaparte in a very small space.

Mme. Bonaparte’s lips lifted in a rueful smile. “No. My stepfather’s cannon have done so already.”

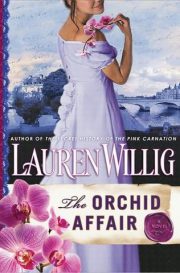

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.