“We could, but since I’ll be spending the bulk of the day at the mall and the outlets browbeating three boys into trying on back-to-school clothes, I’d probably just shoot the first male who spoke to me.”

“Girls’ night in it is.”

“Perfect.”

Avery boxed up the takeout herself, put it on Clare’s tab.

“Thanks. See you tomorrow.”

“Clare,” Avery said as Clare walked to the door. “Saturday, I’ll bring a second bottle of wine, something gooey for dessert. And my pj’s.”

“Even better. Who needs a man when you’ve got a best girl pal?”

Clare laughed as Avery shot a hand in the air.

She stepped out and nearly bumped into Ryder.

“Two out of three,” she said. “I saw Beck earlier. Now I just need Owen for the hat trick.”

“Heading over to Mom’s. He and Beck are working in the shop. I’ll give you a ride,” he said with a grin. “I just took a dinner order, since Mom says it’s too hot to cook.”

Clare lifted her bag. “I’m with her. Say hi for me.”

“Will do. Looking good, Clare the Fair. Wanna go dancing?”

She shot him grin for grin as she pushed the Walk button on the post. “Sure. Pick me and the boys up at eight.”

She got lucky with the timing, and headed across with a wave. She tried to remember the last time a man had asked her to go dancing and meant it.

She just couldn’t.

The Montgomery Workshop was big as a house and designed to look like one. It boasted a long covered porch—often crowded with projects in various stages—including a couple of battered Adirondack chairs waiting for repair and paint, for two years and counting.

Doors, windows, a couple of sinks, boxes of tile, shingles, plywood, and various and sundry items salvaged from or left over from other jobs mixed together in a rear jut they’d added on when they’d run out of room.

Because the hodgepodge drove him crazy, Owen organized it every few months, then Ryder or Beckett would haul something else in, and dump it wherever.

He knew damn well they did it on purpose.

The main area held table tools, work counters, shelving for supplies, a couple of massive rolling tool chests, stacks of lumber, old mason jars and coffee cans (labeled by Owen) for screws, nails, bolts.

Here, though it would never fully meet Owen’s high standards, the men kept at least a semblance of organization.

They worked together well, with music from the ancient stereo recycled from the family home banging out rock, a couple of floor fans blowing the heat around, the table saw buzzing as Beckett fed the next piece of chestnut to the blade.

He liked getting his hands on wood, enjoyed the feel of it, the smell of it. His mother’s Lab-retriever mix Cus—short for Atticus—stretched his massive bulk under the table saw for a nap. Cus’s brother, Finch, dropped a baseball squeaky toy at Beckett’s feet about every ten seconds.

Dumbass lay on his back in a pile of sawdust, feet in the air.

When Beckett turned off the saw, he looked down into Finch’s wildly excited eyes. “Do I look like I’m in play mode?”

Finch picked up the ball in his mouth again, spat it on Beckett’s boot. Though he knew it only encouraged the endless routine, Beckett snagged the ball, then heaved it out the open front door of the shop.

Finch’s chase was a study in mad joy.

“Do you jerk off with that hand?” Ryder asked him.

Beckett wiped the dog slobber on his jeans. “I’m ambidextrous.”

He took the next length of chestnut Ryder had measured and marked. And Finch charged back with the ball, dropped it at his feet.

The process continued, Ryder measuring and marking, Beckett cutting, Owen putting the pieces together with wood glue and clamps according to the designs tacked on sheets of plywood.

One set of the two floor-to-ceiling bookshelves that would flank The Library’s fireplace stood waiting for sanding, staining, for the lower cabinet doors. Once they’d finished the second, and the fireplace surround, they’d probably tag Owen for the fancy work.

They all had the skills, Beckett thought, but no one would deny Owen was the most meticulous of the three.

He turned off the saw, tossed the ball for the delirious Finch, and noticed it had gone dark outside. Cus rose with a yawn and stretch, leaned against Beckett’s leg for a rub before wandering out.

Time to call it, Beckett decided, and got three beers out of the old shop refrigerator. “It’s oh-beer-thirty,” he announced and walked over to hand bottles off to his brothers.

“I hear that.” Ry kicked the ball the dog dropped at his feet out the open window with the same accuracy he’d kicked a football through the goalposts in high school.

With a running leap, Finch soared through after it. Something crashed on the porch.

“Did you see that?” Beckett demanded over his brothers’ laughter. “That dog’s crazy.”

“Damn good jump.” Ryder wet his thumb, rubbed it on the side of the bookcase. “That’s pretty wood. The chestnut was a good call, Beck.”

“It’s going to work well with the flooring. The sofa in there needs to be leather,” he decided. “Dark, but rich, with lighter leather on the chairs for contrast.”

“Whatever. The ceiling lights Mom ordered came in today.” Ryder took a pull of his beer.

Owen took out his phone to make a note. “Did you inspect them?”

“I was a little busy.”

Owen made another note. “Mark the boxes? Put them in storage?”

“Yeah, yeah. Marked and in the basement at Vesta. The dining room lights—ceiling and sconces—came in, too. Same deal.”

“I need the packing slips.”

“They’re on-site, Nancy.”

“We’ve got to keep the paperwork organized, Jethro.”

Finch trotted back in, dropped the ball, banged his tail like a hammer.

“See if he’ll do it again,” Beckett suggested.

Obliging, Ryder kicked it out the window. The dog sailed after it. Something crashed. Intrigued, Dumbass wandered over, put his paws on the sill. After a moment he tried crawling out.

“I’ve got to get a dog.” Owen sipped his beer as they watched D.A.’s back legs kicking and scrabbling. “I’m getting a dog as soon as we get this job finished.”

They closed up, and taking the beer outside, spent another fifteen minutes talking shop, throwing the ball for the indefatigable Finch.

The cicadas and lightning bugs filled the strip of lawn and surrounding woods with sound and sparkles. Now and again, an owl worked up the energy to hoot mournfully. It made Beckett think of other sultry summer nights, with the three of them running around as tirelessly as Finch. With the lights on in the house on the rise as they were now.

When the lights flicked on and off, on and off, it was time to come in—and always too soon.

He’d wondered—and worried a little—about his mother, alone up here in the big house tucked in the woods. When his father had died—and that had been hard—the three of them had basically moved back home. Until she’d booted them out again after a couple months.

Still, for probably another year, at least one of them would find an excuse to spend the night once a week or so. But the simple fact was, she did fine. She had her work, her sister, her friends, her dogs. Justine Montgomery didn’t rattle around in the big house. She lived in it.

Ryder nodded toward the house where the porch and kitchen lights—in case they came back in—and their mother’s office light shone.

“She’s up there, hunting on the Internet for more stuff.”

“She’s good at it,” Beckett said. “And if she didn’t spend the time, and have a damn good eye, we’d be chained down doing it.”

“You do anyway,” Ryder pointed out. “Mister Dark but Rich with Contrast.”

“All part of the design work, bro.”

“Speaking of which,” Owen put in, “we still need the safety lights and exit signs for code.”

“I’m looking. We’re not putting up ugly.” Beckett stuck his hands in his pockets, dug in on the point. “I’ll find something that works. I’m going to head out. I can give you most of tomorrow,” he told Ryder.

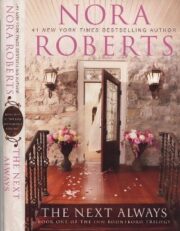

"The Next Always" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Next Always". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Next Always" друзьям в соцсетях.