I wanted to get rid of the Morning Star, and I wanted the Watchers to be free of its curse. But the Grigori were not permitted to carry the sword. “Your husband can pass beyond the seven gates,” the elder Grigori said. “And he knows the names of the angels who rule the planets. Perhaps he can invoke one of our brothers from the highest realms. The sword should be returned to its original home.”

“You mean heaven,” I said, and the elder Grigori nodded.

It was true. The stars had always been George’s favorite subject when he was in Paris studying with the mages. But he was not strong enough to complete such a ritual. I could not allow him to risk his health for this. “We’ll have to find another way,” I said, my hand going protectively to the sword at my side.

“Of course.” The two Grigori bowed and took their leave. “We will speak again soon, Duchess. In the meantime, we will guard you and your family.”

I wished I could simply turn the Morning Star over to the elder Grigori and be done with it. Miechen and Grand Duke Vladimir were both horrified that I should even consider letting such a valuable weapon go. But the tsar agreed with me; we both knew it did not belong in this world. The Grigori could not be freed from their curse, but I could ensure they would never again become the servants of a tyrant like Konstantin Pavlovich. For the present, the Morning Star would remain with me for safekeeping.

40

In the end, George did not get better. The wedding ball did not happen. Winter melted into spring, and the empress finally allowed me to send for the Tibetan doctor. I’d been continuing my studies with him and was certain he would be able to discover the source of George’s illness when I had not. Nor had any of the tsar’s physicians. Or perhaps they had and were too frightened to tell the tsar and the empress the truth. Because none of their suggested cures seemed to work.

Dr. Badmaev smiled at us both kindly after he examined George. “I am afraid the air in St. Petersburg is too cold and damp for you, Your Imperial Highness. A drier, warmer climate would be much more suitable.”

“Such as the Crimea?” I asked.

“Perhaps even farther south,” the Tibetan said as he began to pack his instruments back into his black bag. “I would suggest the Caucasus or even northern Africa. Algiers is nice this time of year.”

George took my hand in his. “Wherever you wish, Katiya,” he said quietly.

“Can you tell us exactly what is wrong with him, Doctor?” I asked. All along I’d had my own suspicions, but I prayed I wasn’t right.

“Oh, definitely. The wound the grand duke received from his duel with the crown prince of Montenegro continues to heal slowly. You yourself saw that his cold light seems to gather around his chest. But that should improve with time. The lung fever has me more concerned. I fear it may be consumption.”

Dr. Badmaev could not have given a more depressing diagnosis. I knew doctors in Germany and France were studying the mycobacteria that caused tuberculosis and were rushing to find a cure. Papa had asked Dr. Pavlov at the Institute in St. Petersburg to consider the disease a priority as well. But there was still so much modern medicine did not understand. Dr. Badmaev had given my husband a death sentence. I pulled George’s hand to my lips and kissed it.

“I suppose we should tell my parents,” he said gloomily.

“I’ll go and send for them,” I said, getting up in a daze.

Dr. Badmaev patted me on the shoulder as I walked past him. “Do keep me informed of your arrangements, Your Imperial Highness. We will find a way of continuing your lessons. There are Tibetan herbs your husband can take that will ease his symptoms, but we cannot completely cure the disease.”

The tsar and the empress refused to believe Dr. Badmaev’s diagnosis, but they were willing to send us south to the Caucasus for the dry air. “There is a Romanov villa in the mountains where you can stay,” the empress said. “It’s very peaceful there. Perhaps you’ll be able to return in a few months.”

Each grand duke and duchess had an opinion on the best warm climate for George. The Mikhailovichi branch had grown up in Tbilisi, where Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolayevich had been viceroy for many years. Militza thought we should return to Cairo, of course. Miechen and Grand Duke Vladimir, who were fond of gambling, praised the merits of the French Riviera.

“There is a school of medicine in Nice,” George said, his chin on my shoulder and his arms around my waist as we looked at the globe in his father’s study.

“Dr. Bokova mentioned the university in Marseille as well,” I said, turning around in his arms. One of the very first Russian women to become a doctor as well as a dear friend, she had agreed with the Tibetan’s diagnosis and recommended that we travel to a city where we’d be close to the leading doctors and researchers. But I knew George needed someplace quiet.

Dr. Bokova also told me I should take care of my own health. “Tuberculosis is extremely contagious,” she had warned me. “If you remain with your young husband, you will eventually contract the disease as well.”

I said nothing to George of this conversation as we mulled over our choices. Together we would defeat the disease, or die.

41

October 1891, Marseille, France

“Honestly, Katiya, must you argue with your professors every week?” George asked me. “This is the third time this month.”

I sighed as I threw my books down onto my desk in our shared study. Our small but fashionable villa sat high on a rocky cliff outside of Marseille, looking down at the sapphire-blue waters of the Mediterranean. We were close enough to the city that the university was only a short carriage ride away and visitors could reach us easily. In the few short months since we’d moved to France, most of our family in Russia had come. My parents, George’s parents, George’s brother Nicholas, his aunt Miechen and uncle Vladimir. My step-aunt Zina and cousin Dariya. Even the expatriates of the family, my Leuchtenberg uncles, had dropped in on us for dinner several times.

I still could not believe we were really here. I was officially a university student. My dreams of becoming a doctor were finally about to come true. My first day of attending lectures I’d sat in awe of the professor, too overwhelmed with emotion to even take notes. The sound of the renowned instructor’s voice faded to the background as I inhaled the scents of the dusty books and chalk and felt the smooth aged wooden desk beneath my fingertips. I was in a large semicircular room, surrounded by mostly young men, all solemnly scribbling notes as the gray-haired man in front of us droned on about scientific theory. Only one other female joined me in this class; she was an older woman who I later discovered was a midwife and was auditing the lectures.

I quickly caught up to my fellow students over the next few weeks, saying a silent prayer of thanks to my father and his enormous medical library at home. I had been more than adequately prepared for my studies at the university. But the practical knowledge I’d learned from Dr. Badmaev, as well as some of the more spiritual aspects of Eastern medicine, seemed to be at odds with what the European scientists were teaching.

George was right; it seemed as if I were constantly antagonizing my professors with something Badmaev had taught me: a technique or a medical preparation that worked just as well as, if not better than, traditional Western medicine. And then there were the stubborn old men who still did not approve of higher education for women. Most of the younger professors were supportive; some were even married to female mathematicians and chemists. But members of the faculty who’d been there the longest shared the mind-set of my father-in-law: women belonged at home in the nursery and in the kitchen, not in a classroom.

George rubbed his forehead with a sigh, but he still managed a smile for me. He looked more tired this afternoon, I thought worriedly. “What was it this time?” he asked.

I made tea for both of us. The elegant silver samovar that sat in the corner of the sunshine-filled study had been a wedding present from my parents. This was our favorite room in the house. I would study my lecture notes from the university while George concentrated on his plans for an observatory. “My anatomy professor insists that I not be allowed to dissect the male cadavers,” I said. “He thinks it would be most improper!”

My husband’s eyes twinkled in amusement as he looked up from his star charts. “And did you tell him you were already well versed in dismemberment?”

I set a silver-handled glass of tea down on his desk and kissed him on the cheek before sinking into a chair nearby. “I do not think that would have helped my case.”

“You will have other opportunities,” George said, before succumbing to a fit of coughing.

Alarmed, I rushed to his side as he pulled his handkerchief out of his pocket. With relief, I noted there was no blood this time. We were doing everything we could for him. The open-air treatment, advocated by most European doctors, offered the most hope for restoring George’s strength. He still had the occasional fever, and frequently I woke in the night to find him sweating and restless, with a rapid, weak pulse. But as the weeks went on, his appetite had been improving slowly, and the fresh sea air seemed to bring the color back to his cheeks.

He pushed back from his desk and got up, pulling away from me. “How do you stand this, Katiya? You are married to a corpse.”

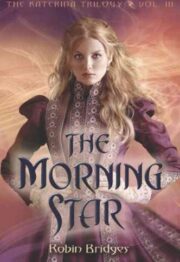

"The Morning Star" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Star". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Star" друзьям в соцсетях.