‘That’s rough.’

‘Yes. He was absolutely frantic. I didn’t know how to comfort him; not properly.’

She retreated momentarily into her hair.

‘And you’re going to get married?’

‘Yes… Well, Heini doesn’t talk a lot about getting married because he’s a musician… an artist… and they don’t talk much about bourgeois things like marriage — but we’re going to be together. Properly, I mean. We were going to go away together after the concert, to Italy. I’d have gone earlier but my parents are very old-fashioned… also there was the thing about Chopin and the études.’

The fork which Quin had been conveying to his mouth stayed arrested in his hand. ‘I’m sorry, I’m afraid you’ve lost me. How do Chopin études come into this?’

Too late, Ruth realized where she was heading and looked with horror at her empty glass, experiencing the painful moment when it becomes clear that what has been drunk cannot be undrunk. It had been so lovely, the wine, like drinking fermented hope or happiness, and now she was babbling and being indiscreet and would end up in the gutter, a confirmed absinthe drinker destined for a pauper’s grave.

But Quin was waiting and she plunged.

‘Heini had a professor who told him that Chopin thought that every time he made love he was depriving the world of an étude. I mean that… you know… the same energy goes into composing and… the other thing. A sort of vital force. And this professor thought it was good for Heini to wait. But then Heini found out that the professor was wrong about the way to finger the Appassionata, so then he thought maybe he was wrong about Chopin too. Because there was George Sand, wasn’t there?’

‘There was indeed,’ said Quin, deeply entertained by this gibberish. It wasn’t till they had finished the meal and Ruth, moving nimbly in the gathering darkness, had cleared away and packed up the hamper, that he said: ‘I’ve been thinking what to do. I think we must get you out of Vienna to somewhere quiet and safe in the country. Then we can start again from England. I know a couple of people in the Foreign Office; I’ll be able to pull strings. I doubt if anyone will bother you away from the town and I shall make sure that you have plenty of money to see you through. With your father and all of us working away at the other end we’ll be able to get you across before too long. But you must get away from here. Is there anyone you could go to?’

‘There’s my old nurse. She lives by the Swiss border, in the Vorarlberg. She’d have me, but I don’t know if I ought to inflict myself on anyone. If I’m unclean —’

‘Don’t talk like that,’ he said harshly. ‘And don’t insult people who love you and will want to help you. Now tell me exactly where she lives and I’ll see to everything. What about tonight?’

‘I’m going to stay here. There’s a camp bed.’

He was about to protest, suggesting that she come back to Sacher’s, but the memory of the German officers crowding the bar prevented him.

‘Take care then. What about the night watchman?’

‘He won’t come into my father’s room. And if he does, he’s known me since I was a baby.’

‘You can’t trust anyone,’ he said.

‘If I can’t trust Essler, I’ll die,’ said Ruth.

At two in the morning, Quin got out of bed and wondered what had made him leave a girl hardly out of the schoolroom to spend a night alone in a deserted building full of shadows and ghosts. Dressing quickly, he made his way down the Ringstrasse, crossed the Theresienplatz, and let himself in by the side entrance.

Ruth was asleep on the camp bed in the preparation room. Her hair streamed onto the floor and she was holding something in her arms as a child holds a well-loved toy. Professor Berger’s master key unlocked also the exhibition cases. It was the huge-eyed aye-aye that Ruth held to her breast. Its long tail curved up stiffly over her hand and its muzzle lay against her shoulder.

Quin, looking down at her, could only pray that, as she slept, the creature that she cradled was carrying her soul to the rain-washed streets of Belsize Park, and the country which now sheltered all those that she loved.

Chapter 3

Leonie Berger got carefully out of bed and turned over the pillow so that her husband, who was pretending to be asleep on the other side of the narrow, lumpy mattress, would not notice the damp patch made by her tears. Then she washed and dressed very attentively, putting on high-heeled court shoes, silk stockings, a black skirt and crisply ironed white blouse, because she was Viennese and one dressed properly even when one’s world had ended.

Then she started being good.

Leonie had been brave when they left Vienna, secreting a diamond brooch in her corset which was foolhardy in the extreme. She had been sensible and loving, for that was her nature, making sure that the one suitcase her husband was allowed to take contained all the existing notes for his book on Mammals of the Pleistocene, his stomach pills and the special nail clippers which alone enabled him to manicure his toes. She had been patient with her sister-in-law, Hilda, who was emigrating on a domestic work permit, but had fallen over her untied shoelaces as they made their way onto the Channel steamer, and she had cradled the infant of a fellow refugee while his mother was sick over the rails. Even when she saw the accommodation rented for them by their sponsor, a distantly related dentist who had emigrated years earlier and built up a successful practice in the West End, Leonie only grumbled a little. The rooms on the top floor of a dilapidated lodging house in Belsize Close were cold and dingy, the furniture hideous, the cooking facilities horrific, but they were cheap.

But that was when she thought Ruth was waiting for them in the student camp on the South Coast. Since the letter had come from the Quaker Relief Organization to say that Ruth was not on the train, Leonie had started being good.

This meant never at any moment criticizing a single thing. It meant inhaling with delight the smell of slowly expiring cauliflower from the landing where a female psychoanalyst from Breslau shared their cooker. It meant admiring the scrofulous tom cats yowling in the square of rubble that passed for a garden. It meant being enchanted by the hissing gas fire which ate pennies and gave out only fumes and blue flames. It meant angering no living thing, standing aside from houseflies, consuming with gratitude a kind of brown sauce which came in bottles and was called coffee. It meant telling God or anyone else who would listen at all hours of the day and night, that she would never again complain whatever happened if only Ruth was safe and came to them.

By 7.30, Leonie had prepared breakfast for her family — bread spread with margarine, a substance they had never previously tasted — and sent Hilda, with red-rimmed eyes, off to her job as housemaid to a Mrs Manfred in Golders Green. If she hadn’t been so desperate about Ruth, Leonie would have greatly pitied her sister-in-law, who was constantly bitten by Mrs Manfred’s pug and found it impossible to believe that a bath, once cleaned, also had to be dried, but now she could only be thankful that Hilda would not be around to ‘help’ her with her chores.

At eight o’clock, Uncle Mishak, the English dictionary in the pocket of his coat, set off up the hill to join the long queue of foreigners in Hampstead Town Hall who waited daily for news of relatives, for instructions, for permission to remain — and as he walked, a tiny compact figure stopping to examine a rose bush in a garden or address an unattended dog, he was hailed by the acquaintances this kind old man had made even in the ten days he had been in exile.

‘Heard anything yet?’ asked the man in the tobacco kiosk, and as Mishak shook his head: ‘There’ll be news today, maybe. They’re coming over all the time. She’ll come, you’ll see.’

The cockney flower seller with the feather in her battered hat, from whom Mishak had bought nothing, told him to keep his pecker up; a tramp with whom he’d shared a park bench one afternoon stopped to ask after Ruth.

And as Uncle Mishak made his way up the hill, Professor Berger, holding himself very erect, forcing himself to swing his walking stick, made his way downhill for the daily journey to Bloomsbury House where a bevy of Quakers, social workers and civil servants tried to sort out the movements of the dispossessed — and as he walked through the grey streets whose very stones seemed to be permeated with homesickness, he raised his hat to other exiles going about their business.

‘Any news of your daughter?’ enquired Dr Levy, the renowned heart specialist who spent his days in the public library studying to resit his medical exams in English.

‘You’ve heard something?’ asked Paul Ziller, the leader of the Ziller Quartet. He had no work permit, his quartet was disbanded, but each day he went to the Jewish Day Centre to practise in an unused cloakroom, and each night he dressed up in a cummerbund to play bogus gypsy music in a Hungarian restaurant in exchange for his food.

Left alone in the dingy rooms, Leonie continued to be good. There were plenty of opportunities for this as she set about the housework. The thick layer of grease where the psychoanalyst’s stew had boiled over would normally have sent her raging down to the second-floor front where Fräulein Lutzenholler sat under a picture of Freud and mourned, but she wiped it up without a word. The bathroom, shared by all the occupants, provided almost unlimited opportunities for virtue. There was a black rim around the bath, the soaked bathmat was crumpled up in a corner… and Miss Bates, a nursery school teacher and the only British survivor at Number 27, had hung a row of dripping camiknickers on a sagging piece of string.

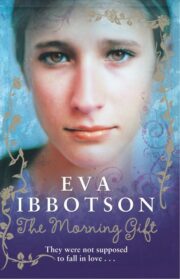

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.