In earlier times, Ruth might have sought sanctuary in a temple or a church. Now, homeless and desolate, she came to this place.

It was Tuesday, the day the museum was closed to the public. Silently, she opened the side door and made her way up the stairs.

Her father’s room was exactly as he had left it. His lab coat was behind the door; his notes, beside a pile of reprints, were on the desk. On a work bench by the window was the tray of fossil bones he had been sorting before he left. No one yet had unscrewed his name from the door, nor confiscated the two sets of keys, one of which she had left with the concierge.

She put her suitcase down by the filing cabinet and wandered through into the cloakroom with its gas ring and kettle. Leading out of it was a preparation room with shelves of bottles and a camp bed on which scientists or technicians working long hours sometimes slept for a while.

‘Oh God, let him come,’ prayed Ruth.

But why should he come, this Englishman who owed her nothing? Why should he even have got the keys she had left with the concierge? Hardly aware of what she was doing, she pulled a stool towards the tray of jumbled bones and began, with practised fingers, to separate out the vertebrae, brushing them free of earth and fragments of rock. As she bent forward, her hair fell on the tray and she gathered it together and twisted it into a coil, jamming a long-handled paintbrush through its mass. Heini liked her hair long and she’d learnt that trick from a Japanese girl at the university.

The silence was palpable. It was early evening now; everyone had gone home. Not even the water pipes, not even the lift, made their usual sounds. Painstakingly, pointlessly, Ruth went on sorting the ancient cave bear bones and waited without hope for the arrival of the Englishman.

Yet when she heard the key turn in the door, she did not dare to turn her head. Then came footsteps which, surprisingly, were already familiar, and an arm stretched over her shoulder so that for a moment she felt the cloth of his jacket against her cheek.

‘No, not that one,’ said a quiet voice. ‘I think you’ll find that doesn’t match the type. Look at the size of the neural canal.’

She leant back in her chair, feeling suddenly safe, remembering the hands of her piano teacher coming down over her own to help her with an errant chord.

Quin, meanwhile, was registering a number of features revealed by Ruth’s skewered hair: ears… the curve of her jaw… and those vulnerable hollows at the back of the neck which prevent the parents of young children from murdering them.

‘How quick you are,’ she said, watching his long fingers move among the fragmented bones. And then: ‘You had no luck at the Consulate?’

‘No, I had no luck. But we’ll get you out of Vienna. What happened back at the flat? Did you save anything?’

She pointed to her suitcase. ‘Frau Hautermanns warned me that they were coming.’

‘The concierge?’

‘Yes. I packed some things and went down the fire escape. They weren’t after me. Not this time.’

He was silent, still automatically sorting the specimens. Then he pushed away the tray.

‘Have you eaten anything today?’

She shook her head.

‘Good. I’ve brought a picnic. Rather a special one. Where shall we have it?’

‘I suppose it ought to be in here. I can clear the table and there’s another chair next door.’

‘I said a picnic,’ said Quin sternly. ‘In Britain a picnic means sitting on the ground and being uncomfortable, preferably in the rain. Now where shall we go? Africa? You have a fine collection of lions, I see; a little moth-eaten perhaps, but very nicely mounted. Or there’s the Amazon — I’m partial to anacondas, aren’t you? No, wait; what about the Arctic? I’ve brought rather a special Chablis and it’s best served chilled.’

Ruth shook her head. ‘The polar bear was almost my favourite when I was small, but I don’t want to get chilblains — I might drop my sandwiches. You don’t want to go back in time? To the Dinosaur Hall?’

‘No. Too much like work. And frankly I’m not too happy about that ichthyosaurus. Whoever assembled that skeleton had a lot of imagination.’

Ruth flushed. ‘It was old Schumacher. He was very ill and he so much wanted to get it finished before he died.’ And then: ‘I know! Let’s go to Madagascar! The Ancient Continent of Lemuria! There’s an aye-aye there, a baby — such a sad-looking little thing. You’ll really like the aye-aye.’

Quin nodded. ‘Madagascar it shall be. Perhaps you can find us a towel or some newspaper; that’s all we need. I’m sure eating here’s against the regulations but we won’t let that trouble us.’

She disappeared into the cloakroom and came back with a folded towel, and with her hair released from its skewer. There could be doubts about her face thought Quin, with its contrasting motifs, but none about her impossible, unruly, unfashionable hair. Touched now by the last rays of the sinking sun, it gave off a tawny, golden warmth that lifted the heart.

It was a strange walk they took through the enormous, shadowy rooms, watched by creatures preserved for ever in their moment of time. Antelopes no bigger than cats raised one leg, ready to flee across the sandy veld. The monkeys of the New World hung, huddled and melancholy, from branches — and by a window a dodo, idiotic-looking and extinct, sat on a nest of reconstructed eggs.

Madagascar was all that Ruth had promised. Ring-tailed lemurs with piebald faces held nuts in their amazingly human hands. A pair of indris, cosy and fluffy like children’s toys, groomed each other’s fur. Tiny mouse lemurs clustered round a coconut.

And alone, close to the glass, the aye-aye… Only half-grown, hideous and melancholy, with huge despairing eyes, naked ears and one uncannily extended finger, like the finger of a witch.

‘I don’t know why I like it so much,’ said Ruth. ‘I suppose because it’s a sort of outcast — so ugly and lonely and sad.’

‘It has every reason to be sad,’ said Quin. ‘The natives are terrified of them — they run off shrieking when they see one. Though I did find one tribe who believe they have the power to carry the souls of the dead to heaven.’

She turned to him eagerly. ‘Of course, you’ve been there, haven’t you? With the French expedition? It must be so beautiful!’

Quin nodded. ‘It’s like nowhere else on earth. The trees are so tangled with vines and orchids — you can’t believe the scent. And the sunbirds, and the chameleons…’

‘You’re so lucky. I was going to travel with my father as soon as I was old enough, but now…’ She groped for her handkerchief and tried again. ‘I’m sure that tribe was right,’ she said, turning back to the aye-aye. ‘I’m sure they can carry the souls of the dead to heaven.’ She was silent for a moment, looking at the pathetic embalmed creature behind the glass. ‘You can have my soul,’ she said under her breath. ‘You can have it any time you like.’

Quin glanced at her but said nothing. Instead, he took the towel and spread it on the parquet. Then he began to unpack the hamper.

There was a jar of pâté and another of pheasant breasts. There were fresh rolls wrapped in a snowy napkin and pats of butter in a tiny covered dish. He had brought the first Morello cherries and grapes and two chocolate soufflés in fluted pots. The plates were of real china; the long-stemmed goblets of real glass.

‘I think you’ll like the wine,’ said Quin, lifting a bottle out of its wooden coffin. ‘And I haven’t forgotten the corkscrew!’

‘How did you do it all? How could you get all that? How did you have the time?’

‘I just went into a shop and told them what I wanted. It only took ten minutes. All I had to do was pay.’

She watched him lay out the picnic, amazed that he was thus willing to serve her. Was it British to be like this, or was it something about him personally? Her father — all the men she knew — would have sat back and waited for their wives.

When it was finished it was like a banquet in a fairy story, yet like playing houses when one was a child. But when she began to eat, there were no more thoughts; she was famished; it was all she could do to remember her manners.

‘Oh, it’s so good! And the wine is absolutely lovely. It’s not strong, is it?’

‘Well…’ He was about to advise caution but decided against it. Tonight she was entitled to repose however it was brought about.

‘Where have your parents gone to?’ he said presently, as they sat side by side, leaning their backs against a radiator. ‘I mean, what part of London?’

‘Belsize Park. It’s in the north-west, do you know it?’

‘Yes.’ The dreary streets with their dilapidated Victorian terraces, the cat-infested gardens of what had once been a prosperous suburb, passed before his mind. ‘A lot of refugees live there,’ he said cheerfully. ‘And it’s very near Hampstead Heath, which is beautiful.’ (Near, but not very near… Hampstead, at the top of the hill, was a different world with its pretty cottages, its magnolia trees, and the blue plaques announcing that Keats had lived there, and Robert Louis Stevenson, and a famous Admiral of the Fleet.) ‘And Heini will go there too?’

‘Yes; very soon. He’s in Budapest getting his emigration papers and saying goodbye to his father, but there won’t be any trouble. He’s Hungarian and the Nazis don’t have anything to say there. He had to go quickly because he’s completely Jewish. After the goat-herding lady died, my grandfather married the daughter of a rabbi who already had a little girl — she was a widow — and that was Heini’s mother, so we’re not blood relations.’ She turned to him, cupping her glass. ‘He’s a marvellous pianist. A real one. He was going to have his debut with the Philharmonic… three days after Hitler marched in.’

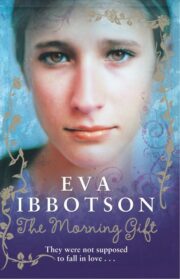

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.