‘Of course, I quite understand,’ said Quin, managing to infuse just the right amount of regret into his voice. Claudine’s father was notoriously easy-going, but there is an etiquette about such things. She had rung him a few days earlier to suggest dinner before he left for Africa and he had been ready to take the evening any way it suited her, for he owed her many hours of pleasure, but the temporary return of Jacques Fleury to attend to business was not unwelcome.

‘How is Jacques? Has he snapped up any more geniuses?’

‘As a matter of fact, he has. He called just before I left. He’s signed up an Austrian boy — a pianist whom he’s going to bring to New York and turn into a star! There was some competition today; he wanted me to come, but three concertos in one afternoon — no thank you!’

‘He won, then, this Austrian?’

‘No. He tied with a Russian and he wasn’t too pleased, I gather. Jacques thinks the Russian is more musical, but you can’t do anything with Russians; they’re so guarded — whereas he can get the Austrian boy over almost straight away. He’s going to bring his girlfriend over too — apparently she’s very pretty and absolutely devoted… worked in some café to pay for Radek’s piano or something. Jacques thinks he can use that at any rate till they’re married; she photographs well! There was some story about a starling…’

She yawned once more; then stretched a hand over the table. ‘I suppose we won’t meet again before you go?’

‘No, I’m off in less than three weeks. And Claudine… thanks for everything.’

‘How valedictory that sounds, darling!’ Her big brown eyes appraised him. ‘Surely we’ll meet again?’

‘Yes. Of course.’

For a moment, he felt the touch of her fingertips, light as butterflies, on his knuckles. ‘I shall miss you, chéri. I shall miss you very much, but I think you need this journey,’ she said. ‘Yes, I think you need it badly.’

The news that Quin was leaving Thameside, which the Vice Chancellor received officially on the first day of the summer term, had affected Lady Plackett so adversely that Verena had been compelled to take her mother aside and make her acquainted with the real state of things.

‘There is no doubt, Mummy, that he means to take me to Africa, but the matter has to be a secret for the time being. I can trust you, I know.’

Lady Plackett had not been as pleased as Verena had hoped. It was a proposal of marriage that she wanted from Quin, not the use of her daughter as an unpaid research assistant. She was still busy bringing Thameside’s morals up to scratch and had managed to get two first-year students sent down who had been caught in flagrante in the gym, so that her daughter accompanying a man, however platonically, to whom she was not married, was far from agreeable. But Verena had always done what she wanted, and Lady Plackett, accepting that times had changed, continued to be civil to Quin and to invite him to the Lodge.

Verena’s preparations, meanwhile, were going well. She had acquired a sunray lamp; she had been to the Army and Navy Stores for string vests and khaki breeches; she rubbed methylated spirits, nightly, into her feet. Some people might have wondered why the Professor was taking so long to inform her of his plans, but Verena was not a person to doubt her worth, and if she had felt any uncertainty, it would have been quelled by Brille-Lamartaine whose increasingly fevered descriptions of the academic femme fatale who had ensnared Somerville fitted her like a glove.

Nevertheless, with the final exams only a week away, Verena felt she could at least give the Professor a hint. He had praised her last essay so warmly that it had brought a blush to her cheek, and the intimate discussion she had had with him on the subject of porous underwear seemed to indicate that the time for secrecy was past.

So Quin was invited to tea, and aware that it was his last social engagement with the Placketts, he set himself to please.

It was a beautiful early summer day, with a milky sky and hazy sunshine. The French windows were open; the view was one Quin had enjoyed so often in previous years when Charlefont was alive and the talk had been easy and unaffected, not the meretricious academic babble he had had to endure from the Placketts.

‘Shall we go out on to the terrace for a moment?’ suggested Verena, and he nodded and followed her while Lady Plackett tactfully hung back. Leaning over the parapet, Quin let his thoughts idle with the lazy river, meandering down to the sea.

‘You always live by water, don’t you?’ the foolish Tansy Mallet had said, and it was true that he lived by water when he could and was likely to die by it, for he still had his sights set on the navy.

But it was not Tansy he thought of now, nor any of the girls he had once known.

They had collected a lot of rivers, he and Ruth. The Varne which she had intended to swim with a rucksack… The Danube which had brought Mishak his heart’s desire… and the Thames by which they’d stood on the night he thought had set a seal on their love. Once more he heard her recite with pride, and an Aberdonian accent so slight that only a connoisseur could have detected it, the words which Spenser had penned to celebrate an earlier marriage. Had she known it was a prothalamium, a wedding ode, that she spoke, standing beside him in the darkness? Had Miss Kenmore told her that?

And suddenly Quin was shaken once more by such an agony of longing for this girl with her lore and her legends, her funniness and the dark places which the evil that was Nazism had dug in her soul, that he thought he would die of it.

It was as he fought it down, this savage, tearing pain, that Verena, beside him, began to speak, and for a moment he could not hear her words. Only when she repeated them, laying a hand on his arm, did he manage to make sense of her words.

‘Isn’t it time we told everyone, Quin?’ she asked — and he recoiled at the intimacy, the innuendo in her voice.

‘Told them what?’

‘That you are taking me to Africa? I know, you see. Brille-Lamartaine told me that you were taking one of your final students and Milner confirmed it. You could have trusted me.’

Horror gripped Quin. Too late he saw the trail of misunderstandings that had led to this moment. But he was too fresh from his images of Ruth to be civil. The words which were forced out of him were cruel and unmistakable, but he had no choice.

‘Good God, Verena,’ he said, ‘you don’t think that I meant to take you!’

The final examinations for the Honours Degree in Zoology took place in the King’s Hall, a large, red-brick building shared by all the colleges south of the river. An ugly, forbidding place, its very walls seemed steeped in the fear of generations of candidates. Dark wooden desks, carefully distanced each from the other, faced a high rostrum on which the invigilators sat. There were notices about not smoking, not eating, not speaking. A great clock, located between portraits of rubicund Vice Chancellors, ticked mercilessly, and the stained floorboards were bare.

To this dire place, Ruth and her friends had crawled, day after day, their stomachs churning… had waited outside, pale with fear and sleeplessness, trying to crack jokes till the bell rang and they were admitted, numbered like convicts, to shuffle to the forbidding desks with their blue folders, the white rectangles of blotting paper which they would see in their dreams for years to come.

But today was the last exam, if the most important. In three hours they would be free! It was the Palaeontology paper, the one in which Ruth would have hoped to excel, but she hoped for nothing now except to survive.

‘It’ll be all right, Pilly.’ Wretched as she was, Ruth managed to smile at her friend, glad that whatever else had gone wrong with her life she had not neglected to help Pilly. ‘Don’t forget to do the “Short Notes” question if there is one; you can always pick up some marks on those.’

The bell rang. The door opened. Even on this bright June morning, the room struck chill. The two invigilators on the platform were unfamiliar: lecturers from another college whose students also had exams this morning. A woman with a tight bun of hair and a purple cardigan; a grey-haired man. Not Quin, who was sailing in a week, and Ruth was glad. If things went wrong, as they had before, she wouldn’t want him watching her.

‘You may turn over your papers and begin,’ said the lady with the bun in a high, clear voice.

A flutter of white throughout the hall… ‘Read the paper through at least twice,’ Dr Felton had said. ‘Don’t rush. Select. Think.’

But it would be better not to select or think too long. Not this morning…

What do you understand by the Theory of Allometric Growth? She could do that; it was a question she’d have enjoyed tackling under different circumstances — the kind of question that enabled one to show off a little. Discuss Osborn’s concept of ‘aristogenesis’ in the evolution of fossil vertebrates. That was interesting too, but perhaps she’d better do the dunce’s question first — Question Number 4. Write short notes on a) Piltdown Man b) Archaeopteryx c) The Great Animal of Maastricht…

Clever candidates were usually warned against the ‘short notes’ questions; they didn’t give you a chance to excel — but she wasn’t a clever candidate now, she was Candidate Number 209 and fighting for her life.

Verena had started writing already; she could hear her scratching with her famous gold-nibbed pen. Verena frightened her these days. Verena was solicitous, her eyes bored into Ruth.

But Verena didn’t matter. Nothing mattered except to get through the next three hours of which seven minutes had already passed.

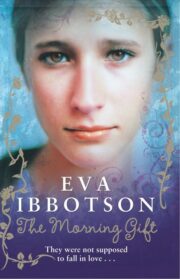

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.