Her friends, of course, saw that she looked ill; that she had lost her appetite.

‘What is it, Ruth?’ Pilly begged day after day — and day after day Ruth said, ‘Nothing. I’m fine. I’m just a bit worried about Heini, that’s all.’

From being a girl tipped to get a First, she became someone whom the staff hoped would simply last the course. Dr Elke wanted to speak to her and then, for reasons of her own, decided against it and Dr Felton, who normally would have made it his business to find out what ailed her, was himself struggling through his days, for the Canadian ballet dancer, to everyone’s consternation, had produced twins. The babies were enchanting — a boy and a girl — so that Lillian, after years of frustration, achieved in one fell swoop a perfect family, but among their accomplishments, the babies did not number an ability to sleep. Night after night, poor Dr Felton paced his bedroom and thought wistfully of the days when his wife’s thermometer was all he had to contend with. He knew that Ruth was unwell, that her work was slipping, but he too accepted the general opinion: that she was anxious about Heini, that her work at Thameside was now second to her life with him.

There was only one treat which Ruth allowed herself during those wretched weeks, and it arose out of a conversation she had with Leonie before her mother went north.

‘That old philosopher,’ Ruth had asked. ‘The one who used to meditate on the bench outside the Stock Exchange. What happened to him?’

‘Oh, they locked him away in a Swiss sanatorium years ago. He was completely batty — when they came to clear up his flat they found it full of women’s underwear he’d stolen from the shops, and he treated his housekeeper like dirt.’

That settled it. A man could be mad and one could still heed his words; even being an underwear fetishist could be forgiven — but ill-treating one’s housekeeper was beyond the pale.

And then and there, Ruth gave up her long struggle to love Verena Plackett.

The results of the first round of the piano competition were a surprise to no one. Heini was through, as were the two Russians and Leblanc; and the second round confirmed the general opinion that the winner must come from one of those four. But the Russians, though exceedingly gifted, had been shut away in their hotel under the ‘protection’ of their escorts and Leblanc was a remote, austere man whom it was difficult to like. By the time of the finals in the Albert Hall, Heini, with his winning personality and his now well-known romance, was the public’s undoubted favourite.

‘I feel so sick,’ said Ruth, and Pilly, beside her, pressed her hand.

‘He’ll win, Ruth. He’s bound to. Everyone says so.’

Ruth nodded. ‘Yes, I know. Only he was so nervous. All last night he kept waking up.’

All last night, too, Ruth had stayed awake herself, making cocoa for Heini, stroking his head till he slept, but not able to sleep again herself. Not that that mattered much: sleep was not really one of her accomplishments these days.

A surprising number of people had come to the Albert Hall for the finals of the Bootheby Piano Competition. Of the six finalists, three had played the previous day: one of the Russians, a Swede, and Leblanc whom Heini particularly feared. Today — the last day — would start with the pretty American girl, Daisy MacLeod, playing the Tchaikovsky and end with the tall Russian, Selnikoff, playing the Rachmaninoff — and in between, came Heini. Heini had been disappointed when they drew lots: he had hoped to play at the end. Whatever people said, the last performer always stayed in people’s minds.

The orchestra entered, then the conductor. To get Berthold to conduct the BBC Symphonia for the concertos was a real coup for the organizers. Heini, rehearsing with them in the morning, had been over the moon.

On Ruth’s other side, Leonie turned to smile at her daughter. She had come down from Manchester and meant to stay till the exams the following week. Her anxiety about Ruth, who was clearly unwell, was underlain by a deeper wretchedness for she knew that if Heini won it meant America and the idea of losing Ruth was like a stone on her chest.

‘You must not show it,’ Kurt had said. ‘You must want it. She’ll be safe there and nothing matters except that.’

Since March, when Hitler, not content with the Sudetenland, had marched into Prague, few people believed any more in peace.

The whole row was filled with Ruth’s friends and relations. Beside Pilly sat Janet and Huw and Sam. The Ph.D. student from the German Department was there, and Mishak and Hilda… even Paul Ziller had come and that was an honour. Ziller was very preoccupied these days; the chauffeur from Northumberland was pursuing him, begging to be heard — there was pressure from all sides for him to lead a new quartet.

It was hot in the hall with its domed roof. Leonie, dressed even at three in the afternoon like a serious concert-goer in a black skirt and starched white blouse, fanned herself with the programme. And now Daisy MacLeod came onto the platform with her dark hair tied back with a ribbon and her pretty blue dress and shy smile, and a storm of clapping greeted her. The Tchaikovsky suited her. She was very young; there were rough passages and once or twice she lost the tempo, but Berthold eased her back and the performance was entirely pleasing. Whether she won or not, she was assured of a career.

The applause was loud and prolonged, bouquets were carried onto the stage; the judges wrote things down and nodded. Ruth liked Daisy, liked her playing, but: ‘Oh, God, don’t let her win.’

And now the culmination of all those weeks of worry and work. Heini came on the platform with his light, springing gait; bowed. Ruth had searched the flower shops of Hampstead for the perfect camellia, Leonie had ironed each ruffle on his shirt, but the charm, the appealing smile, owed nothing to their ministrations. His platform manner had always been one of his strong points, and Ruth looked up at the box where Mantella sat with Jacques Fleury, the impresario, who as much as the judges held the keys to heaven or hell. Mantella was important, but Fleury was god — he could waft Heini over to the States, could turn him into a virtuoso and star.

Berthold raised his baton; the orchestra went into the tutti… the theme was stated gently by the violins, taken up by the woodwind…

And everybody smiled. Mantella had been right. The audience was ready for this music.

When the angels sing for God they sing Bach, but when they sing for pleasure they sing Mozart, and God eavesdrops.

Heini waited, looking down at the keys in that moment of stillness she had always loved. Then he came in, stating the theme so rightly, so joyfully… and she let out her breath because he was playing marvellously. Obviously he had been nervous only to the necessary degree: now he was purged of everything except this limpid, tender, consoling music which flowed through him from what had to be heaven if there was a heaven anywhere. He had performed this miracle for her the first time she heard him and she would never tire of it, never cease to be grateful. All her past was contained in the notes he played — all her life in the city she once thought would be her home for ever. No wonder she had been punished when she forsook that world.

The melody climbed and soared, and she climbed with it, out of her sadness, her wretchedness, the discomforts of her body… out and up and up. Ah God, if only one could stay up there; if only one could live like music sounded — if only the music never stopped!

The slow movement next. She was old enough now for slow movements, she was immemorially old. It must be possible to love someone who could draw such ravishment from the piano. And it was possible. She could love Heini as a friend, a brother, someone whose childishness and selfishness were of no account when set against this gift. But not as a man — not ever, now that she knew… and suddenly the platform, Heini himself, grew blurred in a mist of tears, for it was a strange cross that Fate had laid on her, ordinary as she was: an inescapable, everlasting love for a man to whom she meant nothing.

The last movement was a relief, for no one could live too long in the celestial gravity of the Andante — and here now was the famous theme! It would have to be a very unusual starling to have sung that melody, but what did it matter? Only Mozart could be so funny and so beautiful at the same time! Everyone was happy and Ziller was nodding his head which was important. Ziller didn’t like Heini, but he knew.

Then suddenly it was over and Heini rose to an ovation. People stamped and cheered; a group of schoolgirls threw flowers on to the stage — there were always schoolgirls for Heini — and in his box, Jacques Fleury had risen to his feet.

‘I’m sorry I said he was too long in the bath,’ said Leonie, dabbing her eyes. ‘He was too long, but I’m sorry I said it.’

He had to have won. There could be no doubt… not really.

But now Berthold returned, and the tall Russian, Selnikoff, to play the Rachmaninoff.

And, God, he was good! He was terrifyingly good, with the weight of his formidable training behind him and the outsize soul that is a Russian speciality.

Ruth’s nausea was returning. Please, God — oh, please… I’ll do anything you ask, but let Heini have what he so desperately wants.

The dinner, as always at Rules, had been excellent; they’d drunk a remarkable Chablis, and Claudine Fleury, in a little black dress which differed from a little chemise only on a technicality, had made Quin a much-envied man.

Now she yawned as delicately as she did everything. ‘That was lovely, darling. I wish I could take you back, but Jacques is here for another week.’

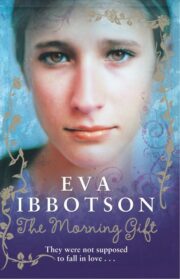

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.