‘It’ll be a desert without you,’ he said and turned away to hide his distress. ‘Elke thought this might happen, but I hoped… Oh, hell!’

‘If it’s any consolation to you, I think next year may see us all scattered,’ said Quin. ‘This war, if it comes, won’t be like the last one. I’ve seen some pretty weird contingency plans, but few of them involve leaving scientists in peace in their universities.’ And as Roger still stood in silence, trying to deal with his sense of loss, Quin put a hand on his arm and said: ‘I’ll take you to Africa, Roger, if you can get away. I’d be glad to. It’s not strictly your line of country, but I think you’d enjoy it.’

‘Thanks — you know how I’d love it, but I can’t leave Lillian. We’re supposed to be taking delivery of an infant at the end of May, sight unseen. A Canadian dancer who’s got into trouble. Lillian thinks it’ll do entrechats as soon as we get it; she’s really thrilled.’

‘I’m glad!’ said Quin warmly. ‘And if you’ve got a vacancy for a godfather, perhaps you’d consider me?’

Roger’s face lit up. ‘The job is yours, Professor.’

Crossing the courtyard after his talk with Roger, Quin encountered Verena accompanied by Kenneth Easton, carrying a squash racket and clearly in the best of spirits.

‘You look very fit,’ said Quin when it was evident that she would not let him pass.

‘Oh I am, Professor!’ said Verena archly. She did not actually invite him to feel her biceps, but this was not necessary. Bare-armed and in shorts, the state of her musculature was evident to anyone with eyes to see. And then: ‘I was wondering what you thought of the Army and Navy Stores? Would you recommend them as the best outfitters before an expedition?’

‘Yes, indeed. They’re excellent — I always use them; you’ll find everything you want there. If you mention my name to Mr Collins, you’ll find him very helpful.’

‘Thank you, I’ll do that. And flea powder? Do you recommend Coopers or Smythsons?’

Quin, who had vaguely gathered that Verena was off on some kind of journey with her Croft-Ellis cousins, came down in favour of Coopers and made his way to his room, leaving Kenneth in a state of deep depression. The sacrifices he had made for Verena were considerable. He travelled fourteen stations on the Underground to partner her in squash; he had stopped saying ‘mirror’ and ‘serviette’ both of which, it seemed, were common, and been corrected when he mispronounced Featherstonehaugh. And yet every time she saw the Professor, Verena bridled and simpered like a schoolgirl. There were times, thought Kenneth, when one wondered if it was all worthwhile.

‘I am leaving,’ announced Heini. ‘I’m going to look for another room.’

Leonie stared at the wild-haired youth who had come back in a towering rage after spending Saturday in town.

‘But why, Heini? What has happened?’

‘I can’t discuss it, but I have to leave. I’m too upset to stay here. I can’t even play.’

This was not strictly true. Heini had been home for half an hour and had considerably decreased the life expectancy of the hired piano by crashing through the Busoni Variations so as to send the dishes rattling on the sideboard.

‘Does Ruth know?’ asked Leonie nervously.

‘Not yet. But she will not be surprised,’ said Heini darkly.

‘Oh, dear. If you’ve quarrelled… I mean, that does happen.’

‘Not this,’ said Heini obscurely. ‘This does not happen. I’ll leave as soon as I’ve found somewhere to go.’

Warring emotions clashed in Leonie’s breast. Ruth would be upset and Leonie would do anything to spare her daughter pain. Yet the thought of Heini being elsewhere rose like an image of Paradise in her mind. To be able to wander in and out of her sitting room at will, to be able to put her feet up in the afternoon… To be able to get into the bathroom!

Not knowing what to say, she retreated into the kitchen where Mishak was looking at the pages of a gardening catalogue lent to him by the lady two houses down.

‘Heini says he is leaving. I think he and Ruth have had some dreadful quarrel.’

Mishak looked up. ‘Where will he go?’

‘I don’t know. He says he’s going to look for another room.’

‘And how will he pay for it?’

Heini had, of course, been living rent-free; the money he had brought from Budapest having been used up long ago.

‘I don’t know. But he’s very determined.’

In Mishak’s mind, as in Leonie’s, there rose a vision of Number 27 without Heini. He imagined hearing the blackbirds in the morning, the rustle of wind in the trees.

‘Do you think he’ll want any supper?’ asked Leonie, preparing to mix the pancakes which, when filled with scraps of various sorts, could fill up large numbers of people at very little expense. ‘He was very upset.’

‘He will want supper,’ said Mishak, and was proved right.

It was Ruth who did not want supper. Ruth who phoned to say she would be late… and who was walking the streets wringing her hands like a Victorian heroine. Ruth who felt disgraced and shamed and wished the earth would open up and swallow her…

For after all, it had happened, the thing she had dreaded that night on the Orient Express. It was prophetic, all the reading she had done there on the Grundlsee. They had not minced their words, those behavioural experts with their three-volumed tomes: Havelock Ellis and Krafft-Ebing and a particularly alarming man called Eugene Feuermann. It was not for nothing that they had devoted chapter after chapter to one of the great scourges of those who seek fulfilment in the act of love.

Anything would have been better than what had happened. There were chapters on nymphomania too, but Ruth would have settled for that. Nymphomania might end badly, but it sounded generous and giving. Someone with nymphomania might expect to live utterly and die whereas…

Why me? thought Ruth, when I was so much looking forward to being with him. And what would Janet say? Could one even mention it to Janet who was so bountiful in the backs of motor cars?

The word drummed in her ear — the dreaded word which branded her as ice cold, as having splinters in her heart as if the Snow Queen herself had put them there. It had begun to drizzle and she pulled up the hood of her loden cape, but the bad weather suited her. Why should the sun shine ever again on someone who was the subject of two whole chapters and a set of tables in Feuermann’s Sexual Psychopathology?

Ruth walked for one hour, and two… and then, tainted or not, she made her way to the Underground. Sooner or later she would have to face Heini and to add cowardice to coldness would solve nothing.

‘Come in.’

Fräulein Lutzenholler sat in her dressing-gown drinking a cup of cocoa with a wrinkled skin, which she had made earlier, spilling the milk. Above her hung the portrait of the couch she had used to see patients in Breslau, a small blue flame hissed in the gas fire, and she was not at all pleased to see Ruth.

‘I am going to bed,’ she announced.

Ruth entered, her hair in disarray, her eyelids swollen. ‘I know; I’m sorry. And I know you can’t help me because I can’t pay you and psychoanalysis only works if you pay the person who’s doing it.’

‘And in any case I am not permitted to practise in England,’ said Fräulein Lutzenholler firmly.

‘But I thought you might know if there’s anything I can do.’ It had been difficult to come into the analyst’s uninviting room and after her remarks about the lost papers on the bus, Ruth had sworn never to consult her again, but it seemed one couldn’t escape one’s fate. ‘I am so unhappy, you see, and I thought there might be something I haven’t understood about my childhood. Something I have repressed.’

Fräulein Lutzenholler sighed and put down her cup. ‘Is it true that Heini is moving away?’ she asked.

Ruth nodded, and something that was almost a smile passed over the analyst’s features, lightening the moustache on her upper lip.

‘It is not so simple, repression,’ she said.

‘No. But I know that if you see something awful when you are small… if your parents… you know if you find them making love. But I never did. When Papa had his afternoon rest everyone crept about and my mother sat in the drawing room with her embroidery like a Grenadier Guard shushing everybody. And anyway our flat had double doors, you couldn’t hear anything. And on the Grundlsee I always fell asleep very quickly because of all that fresh air and though the maids told me about Frau Pollack always wanting gherkins before she let her husband come to her, I don’t think it was a trauma and anyway I haven’t repressed it. And I can’t think —’

Fräulein Lutzenholler frowned. The good humour caused by the news that Heini was leaving had evaporated and she was worried about her hot-water bottle. She had filled it half an hour before and liked to get into bed while it was still in peak condition.

‘What are you talking about?’ she said, spooning the cocoa skin into her mouth. ‘I don’t understand you.’

Ruth, who had shied away from the word all day, now pronounced it.

There was a pause. Fräulein Lutzenholler looked at the clock. ‘Ruth, it is a quarter to eleven. I cannot discuss this with you now. It is a technical problem and there can be very many causes; physiological, psychological…’

‘Oh, please… please help me!’

Fräulein Lutzenholler stifled a yawn.

‘Very well, tell me what happened.’

Ruth began to speak. Her words tumbled over each other, tears sprang to her eyes, her hair fell over her face and was roughly pushed away.

To these outpourings of a tortured soul, Fräulein Lutzenholler listened with increasing and evident displeasure. She put her soiled cup back in its saucer. She frowned.

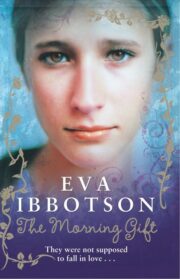

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.