Janet laid a hand on her arm. ‘Try to make sure that he takes them off early on. A man standing there with nothing on and then those dark socks… it can throw you a bit. But after all, you love him. There’s really nothing to worry about at all.’

Janet’s flat was in Bloomsbury, in one of those little streets behind the British Museum. Had she climbed down the fire escape which led from the kitchen, Ruth would have found herself a stone’s throw from the basement where Aunt Hilda worked. Hilda wouldn’t be shocked by what she was about to do. The Mi-Mi were very easy going; everyone in Bechuanaland took love lightly.

But her parents…

Ruth forced her mind away from what her parents would think. She had so hoped that the annulment would be through by now — then she could at least have got engaged to Heini. But it wasn’t and that was her fault and another reason for not keeping him waiting any longer.

The flat was very Bohemian; the furniture was sort of tacked together and there wasn’t much of it and everything was very dusty. Still, that was a good thing. Mimi had been a Bohemian, arriving with her candle and her tiny frozen hands and not fussing any more than the heroine of La Traviata about being married. She had died too, of course, clutching her little muff, but not from sin, from consumption — one had to remember that.

Heini should be here any moment now. She had cleaned the sink and swept the kitchen floor and unwrapped the wine that Janet had brought her as a good luck present. Ruth had been worried about this — Janet was dreadfully hard up — but Janet had waved her protests away.

‘It was a special offer from the Co-op,’ she said.

The wine would be a big help, Ruth was sure of that, remembering what it had done for her on the Orient Express.

Fighting down her nervousness, she opened the door of Corinne’s room which was the one Janet suggested they use. It had a double bed — well, a double mattress — covered in some interesting coloured sacking. Corinne was an art student; there were drawings tacked round the wall which she had done in life class. All the women had breasts which soared upwards and Doric-looking thighs. Heini was going to be very disappointed — perhaps it would be best to make the room properly dark. But when she began to draw the curtains, the bamboo rail came clattering down on to the floor and she only just had time to replace it before the doorbell rang.

‘Heini! Darling!’ But though he embraced her, Heini did not look happy. ‘Is everything all right? Did you get them?’

‘Yes, I did in the end, but I’ve had an awful time. The slot machines were right up against each other and the instructions had been ripped off so the first time I put a sixpence in I got a bar of chocolate — that revolting stuff with squishy cream in the middle.’

‘Oh, Heini; how awful!’ Heini never ate chocolate in case it gave him acne.

‘Then I tried the other one and the money got stuck. I had to hit it with my shoe while some idiot came past and sniggered. I never want to go through that again!’

Guilt surged through Ruth. Heini had asked her to go to the chemist and see to ‘all that’ and it was true that her English was much better than his, but there were words one wasn’t absolutely sure about, even if one looked them up in the dictionary. Particularly if one looked them up in the dictionary. At the same time, she wondered if he had brought the chocolate. She had missed her lunch, but it was probably better not to ask.

‘Anyway, we’re here,’ she said, helping him off with his coat. And then bravely: ‘Would you like a bath?’

Heini nodded — he must have read the same book as she had; the one which said that a bath beforehand was a good idea — and followed her into the bathroom where she lit the geyser and turned on the tap.

The effect was dramatic. There was a loud bang, gusts of steam erupted, and a purple flame.

‘Good God, we can’t use that!’ said Heini. ‘It’s worse than Belsize Park.’

‘You don’t think it’ll calm down?’

‘No I don’t.’ Heini had grabbed a towel and was holding it to his nose. ‘Emile Zola was killed by a leaking stove.’

‘Well, never mind,’ said Ruth, turning it off. (Not all the books had recommended hot baths. Some believed in naturalness.) ‘Let’s go and have some wine.’

They returned to the kitchen and she poured a glass for Heini and another for herself.

‘We’d better drink a toast,’ she said.

Heini smiled: ‘To our love!’ he said.

It was at this moment that they heard a series of frantic, high-pitched squeaks outside on the fire escape. Ruth opened the door and a black cat ran into the room, carrying a bird in its mouth. The bird was a sparrow and it was not yet dead.

‘Oh, God!’

‘Shoo it out for heaven’s sake!’

‘I think it lives here. Janet said something about a cat.’

‘It doesn’t matter if it lives here or not.’

Heini rose, chased the cat out, and bolted the door.

‘We should have killed it,’ said Ruth.

‘I can’t kill cats without a gun.’

‘Not the cat. The bird.’

Feeling distinctly queasy, she lifted her glass and drank. Sour and chill, the wine crashed into her stomach. Seemingly there was wine and wine…

‘Come on, Ruth! Let’s go into the bedroom.’

‘Yes. Only Heini, I’d like to get into the mood a bit. Couldn’t we have some music?’

‘I am in the mood,’ said Heini crossly. But he followed her into the sitting room where a pile of records was heaped untidily onto a low table.

‘Oh, look!’ she said delightedly. ‘They’ve got Highlights from La Traviata.’

But, of course, musicians do not listen to highlights — it is not to be expected — and Heini was beginning to look hurt.

‘You do love me, don’t you?’

‘Heini, you know I do!’

He held out both hands, boyish, appealing. She put hers into them. They made their way into the bedroom. And he was taking off his socks — someone must have warned him! It was going to be all right!’

‘Oh, damnation! This place is a tip! I’ve got a drawing pin in my foot.’

He had subsided on to the bed, clutching his left foot from which, sure enough, a drop of blood now oozed.

‘It’s not the part you pedal with,’ said Ruth who could always read his thoughts. ‘It’s right on the side. But I’ll get a bit of plaster.’

‘And some iodine,’ called Heini as she made for the door. ‘The floor must be knee-deep in germs.’

She found some iodine in the bathroom and a roll of zinc plaster, but no scissors. Carrying the plaster into the kitchen, she searched the drawers but without success. Eventually she took a kitchen knife and started to hack off a strip.

‘It’s stopped bleeding,’ called Heini. ‘If you just disinfect it, it’ll be all right.’

Carrying the iodine into the bedroom, she anointed the sole of Heini’s foot. Heini was being brave, not wincing.

‘We’ll have to wait for it to dry.’

‘It won’t take long,’ he said. ‘Why don’t you get undressed?’

‘I’ll just take the iodine back. It would be awful if we spilled it.’

She went past the life class pictures, past a small grey feather dropped from the breast of the little bird, and restored the iodine bottle. Returning, she found that Heini was in bed.

It could be postponed no longer, then — the living utterly. Ruth crossed her arms and pulled her sweater over her head.

On the same afternoon as Heini was learning to be demonic in Bloomsbury, Quin made his way to the Natural History Museum to confer with his assistant about the coming journey.

‘I’m afraid I have bad news for you,’ said Milner, climbing down from the scaffolding on which he was attending to the neck bones of a brontosaurus.

But he was smiling. Since Quin had told him they were off in June, he had been in an excellent mood.

‘What kind of bad news?’ asked Quin.

‘I’ll tell you in private,’ said Milner mysteriously, and together they made their way through the echoing dinosaur hall to Milner’s cubbyhole in the basement. ‘It’s Brille-Lamartaine,’ he went on. ‘He’s got wind of your trip and he wants to come! He’s been lurking and hinting and making a thorough nuisance of himself. I haven’t said a word, but something must have leaked out.’

‘Good God! I thought he was in Brussels.’

Brille-Lamartaine was the Belgian geologist whose spectacles had been stepped on by a yak. It isn’t often that a member of an expedition is a disaster without a single redeeming feature, but Brille-Lamartaine had achieved this distinction without even trying.

‘I wonder how he heard?’

‘He’s been spending a lot of time at the Geographical Society. Hillborough’s totally discreet but something may have leaked out.’

‘I’ll tell you what,’ said Quin, ‘if he brings up the subject again, tell him I’m bringing a woman. One of my students. A young life-enhancing woman greedy for experience with the opposite sex.’

Milner was appreciative. Brille-Lamartaine was terrified of women and convinced that every one had designs both on his portly frame and his inheritance from a maiden aunt in Ghent.

‘I shall like to do that,’ he said.

But as he left the museum, Quin knew that he could no longer postpone telling his staff that he was leaving. The Placketts could wait till the statutory term’s notice at Easter, but to let Roger and Elke and Humphrey hear the news from others would be unpardonable.

As it happened, Roger was in the lab, using the weekend to catch up with his research, and the look on his face when Quin spoke was hard to bear.

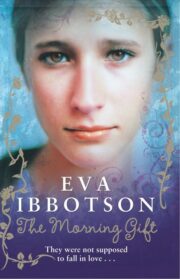

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.