‘Harcar? That’s where the Forfarshire went down? Where Grace Darling rowed to?’

‘Yes. Anyway, I did it. I got the dinghy out at dawn — I was small but I was strong; sailing’s a knack, nothing more. Even so, I don’t know why I wasn’t killed; the currents are terrible there. When I came back he was standing on the shore. He didn’t say anything. He just frogmarched me up to the house and beat me so hard that I couldn’t sit down for a week. But that night when I went to bed, there it was — my night light.’

‘Yes,’ said Ruth, after a pause. ‘I see.’

‘I could do it, Ruth. It’s no trouble to me to be Master of Bowmont. Physical things don’t bother me. I can find a wife —’ He checked himself, ‘a new wife — I can breed sons. But I don’t forget what it did to my father. I don’t forget that my mother died for his dynastic pride. So let someone else have it. I shall be off on my travels again soon in any case. Unless —’ But there was no need to speak to her of the war he was sure would come.

Back in the tower, he took the jacket from her shoulders, turned back the covers.

‘Tomorrow you shall go back to your friends, Rapunzel,’ he said. ‘Now get some sleep.’

The sudden gentleness almost overset her.

‘Can I stay, then?’ she managed to say.

‘Yes, you can stay.’

‘Oh, my dear!’ said Lady Plackett as her daughter turned from the mirror on the evening of the dance. ‘He will be overcome!’ — and Verena smiled for she could not help thinking that her mother spoke the truth.

Miss Somerville’s letter suggesting a party for her birthday had sent Verena to Fortnum’s in search of a suitable dress, where their chief vendeuse had suggested a simple Greek tunic of white georgette for, as she pointed out, Verena’s beauty was in the classical style.

Verena had refused. She wanted, on the night that she hoped would seal her fate, to be thoroughly and unexpectedly feminine and ignoring the ill-concealed disapproval of the saleswoman, she had decided on a gown of strawberry-pink taffeta with a tiered skirt, each tier edged with a double layer of ruffles. The big leg-o’-mutton sleeves too were lined with ruffles, as was the heart-shaped neckline, and wishing to emphasize the youthful freshness which (she was aware) her high intelligence sometimes concealed, she wore a wreath of rosebuds in her hair.

Had this been the informal dance originally planned, her toilette might have been too sumptuous, but the party, as the Placketts hoped, had snowballed to the point where the word ‘informal’ hardly applied. As Verena stepped into her satin sandal — carefully low-heeled since Quin, now past his thirty-first birthday, could not really be expected to grow any more — other girls all over Northumberland were bathing, young men were tying their black ties or putting on dress uniforms, ready to make their way to Bowmont. For after all, it had always been rather special, this sea-girt tower with its absent owner, its fierce chatelaine — and perhaps they knew what Quin knew; that Fate was knocking on the door and pleasure, now, a kind of duty.

Ann Rothley and Helen Stanton-Derby had come over early to help Frances. Helen had brought armfuls of bronze and gold chrysanthemums, of rosehips and traveller’s joy, and disappeared with rolls of chicken wire to transform the drawing room into a glowing autumnal bower while Ann had slipped upstairs to supervise Frances’ toilette. Had Miss Somerville worn anything other than her black chenille and oriental shawl, the County would have been seriously upset, but Ann could sometimes succeed where Martha failed in coaxing her friend’s hair into a less rigorous style and persuading her that a dab of snow-white powder in the middle of her nose did not constitute suitable make-up.

Now the three women sat in the hall, drinking a well-earned glass of sherry before the arrival of the guests.

‘Doesn’t everything look lovely!’ said Ann. ‘You can just see the place preening itself! You’ll see, it’s going to be a tremendous success.’

‘I hope so.’ Frances was looking tired.

‘And Verena being such a heroine, too!’ said Helen, a little blood-stained round the fingers from the chicken wire. ‘We’re all so impressed.’

For Verena’s version of what had happened on the Farnes had gained general currency. Everyone knew that a foreign girl had lost her head and jumped into the sea, putting everyone’s life into jeopardy, that Quin had been furious, and that Verena, by keeping calm and holding the boat steady, had been able to avert a tragedy.

‘I’m not quite sure why the girl jumped in the first place?’ asked Helen. ‘Someone said it was to save that mongrel puppy of yours, but that can’t be right surely?’

‘Yes, that seems to have been the reason,’ said Frances.

Though they could see that Frances didn’t really want to discuss the accident, her friends’ curiosity was thoroughly aroused.

‘It seems such an extraordinary thing to do,’ said Ann. ‘And for a foreigner! I thought they didn’t like animals. Though I must say the cowman was the same — when a calf died you had to drag him away or he’d have spent all night weeping over the cow.’

‘How is he getting on?’

‘He’s gone down to London — they’ve taken him on in the chorus at Covent Garden and the dairymaid’s distraught. Silly creature — he never gave her the least encouragement.’ But the change of subject had not, as Frances hoped, diverted her. ‘What’s she like, this girl? The one who jumped?’

‘She’s blonde too,’ said Frances wearily.

Helen Stanton-Derby sighed. ‘Well, it’s all very unsatisfactory,’ she said. ‘Let’s just hope something can be done about Hitler before the place is flooded out.’

But Ann now was looking upwards — and there stood Verena ready to descend!

Just for a moment, the faces of all three ladies showed the same flicker of unease — a flicker which was almost at once extinguished. It was touching that Verena had taken so much trouble, and in the softer light of the drawing room or beneath the Chinese lanterns on the terrace, the colour of the dress would be toned down. And anyway, it wasn’t what they thought of her dress that mattered — it was how she looked to Quin.

They turned their heads and relief coursed through them. Quin had entered the hall and moved over to the staircase. He meant to welcome her, to tell her how nice she looked.

And up to a point, this was true. Reminded of Verena’s unfortunate tumble on the night she came, touched by his aunt’s mysterious but undoubted affection for the Placketts he smiled at the birthday girl and though Lady Plackett was standing by to pay the necessary compliments, it was he who said: ‘You look charming, Verena. Without doubt, you’ll be the belle of the ball.’

As he led her through to the drawing room, a distant telephone began to ring.

Down on the beach, Ruth was gathering driftwood. It was a job she loved; a kind of useful beachcombing. The puppy was with her; ‘helping’, but cured of the sea. When she went too near the water, he dropped the sticks he had been corralling, and sat on his haunches and howled.

‘It’s going to be a lovely bonfire; the best ever,’ said Pilly, and Ruth nodded, wrinkling her nose with delight at the smell of wood smoke and tar and seaweed, and that other smell… the tangy, mysterious smell that might be ozone but might just be the sea itself. The happiness that Quin had shattered on the boat had returned. She felt that she wanted to stay here for ever, living and learning with her friends.

Looking up, she saw a man come down the cliff path and go into the boathouse, and presently Dr Felton came out and made his way towards them.

‘Your mother telephoned, Ruth. She wants you to ring her back at once. She’s waiting by the phone.’ And seeing her face: ‘I’m sure it’s nothing to worry about. I expect Heini’s come early.’

‘Yes.’ But Ruth’s face was drained of all colour. No one telephoned lightly at Number 27. The phone was in the hall, overheard, rickety. The coins collected for it always came out of a jam jar as important as hers for Heini, one spoke over a buzz of interference. Her mother would not have phoned without a strong reason when she was due home so soon in any case. It could, of course, be marvellous news… Heini on an earlier plane… it could be that.

‘I’ll come with you,’ said Pilly.

‘No, Pilly, I’d rather go alone. You keep the dog.’

The servant was waiting, ready to escort her.

‘If you come with me, miss, I’ll take you to Mr Turton. There’s a bit of a row going on at the house with the guests arriving, but Mr Turton’s got a phone in his pantry. You’ll be private there.’

‘Yes,’ said Ruth. ‘Thank you.’ And swallowed hard because her mouth was very dry, and dredged up a smile, and followed him up the path towards the house.

She had managed the bonfire; she had said nothing to the others. She had joined in the singing and helped with the clearing up. But now, lying beside Pilly in the dormitory, she knew she could endure it no longer, being here in this untouched place which washed one clear of anguish, which deceived one into thinking that the world was beautiful.

She had to get back; she had to get back at once. Three more days here were unendurable now that she knew what she knew — and her mother’s incoherent voice, scarcely audible, came back to her yet again — her desperate efforts to tell all she had to tell against the interruptions and the noise.

It was well past midnight; everyone was asleep. Ruth rose, dressed, scribbled a note by torchlight. She would take only the small canvas bag she used on her collecting trips — Pilly would bring the rest. She’d get a lift to Alnwick and wait for the milk train which connected with the express at Newcastle. It didn’t really matter how long she took, only that she was on her way. Every half-hour she spent here was a betrayal.

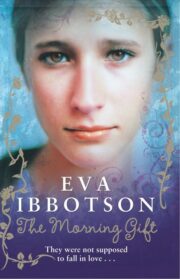

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.