Lady Plackett was spending the day with relatives in Cumberland, but Verena had accompanied the Somervilles to church and heard Quin read the lesson, and now, dressed in a cashmere twin set and pearls, she set about trying to put her classmates at ease. She had already prevented Sam and Huw from trying to dispose of their own coats, explaining that there was a butler there for the purpose and as they took their places at table, she kept a watchful eye on those who might have trouble with their knives and forks. Though Bowmont now was run with a minimum of servants, Verena was aware that the man serving at the sideboard, the maid with her cap and apron, might overwhelm those from simple homes, and since Dr Felton was conversing with Miss Somerville, and Dr Elke was giving Quin an account of a recent journey to Lapland, Verena applied herself to the burden of making small talk, asking Pilly about the average consumption of aspirin per head of the population and enquiring whether Janet’s father managed his parish with one curate or two. She also found time to check up on her protégé, Kenneth Easton. There was no question as yet of inviting Kenneth to the Lodge and she would, for example, have been far from happy to see him tackle an artichoke in melted butter, but considering his origins in Edgware Green, Kenneth was doing rather well.

They took coffee in the drawing room and then Quin rose and offered croquet on the lawn or the use of a rather bumpy tennis court, and bore Roger and Elke off to billiards in the library.

‘Would anyone like to look round the house?’ asked Miss Somerville.

Several students said they would, but before the party could set off, Verena said with proper deference: ‘Would you like me to show them round, Miss Somerville? I’m sure you must want to rest.’

For a moment, Frances’ eyebrows drew together in a frown. But she herself had bidden Verena make herself at home; the girl was only trying to be helpful.

‘Very well — only not the tower, of course.’

Leaving behind a very disgruntled group of students, she left the room. But she did not go upstairs to rest. Instead, she went to the lumber room to fetch a bag of bonemeal and the bulbs that had come the previous day from Marshalls, and made her way to the garden.

Opening the door in the high wall, Aunt Frances saw with displeasure that she was not alone.

A girl was standing with her back to her, one arm raised to a spray of Autumnalis where it climbed, loaded with blossom, up the southern wall. Moving forward angrily to remonstrate, Frances found that the girl was not in fact stealing a rose, but was rather, with some skill, tucking a stray tendril back behind the wire before burying her nose once more in the fragrance of the voluptuous deep-pink flowers.

‘You’re trespassing,’ she said, in no way placated by this appreciation of one of her favourite plants.

The girl spun round, startled, but not, in Miss Somerville’s opinion, suitably cowed. ‘I’m sorry. Professor Somerville said we could go into the grounds, but I can see this would be different. It’s almost like a room, isn’t it? — a hortus conclusus. All it needs is a unicorn.’

‘Well, it’s not going to get a unicorn,’ said Aunt Frances irritably. ‘The sheep are bad enough when they get in.’

She put down her trug and glared at the intruder.

‘I will go,’ promised Ruth. ‘Only it’s so unbelievable, this garden. The shelter… and the way it’s so contained and so rich… and the roses still going on as though it’s summer, and all those tousled, tangly things. And those silver ones like feathers; I don’t know what they’re called.

‘Artemesia,’ said Aunt Frances, still scowling.

‘It’s magic. To have that and the sea, the two worlds… And your scarf!’

‘What on earth are you talking about?’ said Aunt Frances, wondering if the intruder was unhinged, for she was looking at the scarf round her neck as she had looked at the white stars of a lingering clematis.

‘It’s beautiful!’ said Ruth, feeling suddenly remarkably happy. ‘I saw it on the hominid in Professor Somerville’s room, but it looks much better on you!’

‘Don’t be silly, it’s just an old woollen thing. I’m surprised Quin remembered to bring it up.’

But she now had to face the fact that she was in the presence of the missing student, the one who had refused to come to lunch. Like many of the girls of her generation, Frances had spent six months being ‘finished’ in Florence where she had found it difficult to distinguish between Titian and Tintoretto and been unpleasantly affected by the climate. Still, she had retained enough to be aware that the intruder, in spite of her dark eyes, belonged to the tradition of all those Primaveras and garlanded goddesses accustomed to frolicking in verdant meadows. If she had indeed been about to pluck a flower for her hair it would not have been unreasonable. As a Jewish waitress for whom special food had to be prepared, however, she was not satisfactory.

‘You’re the Austrian girl, then? The one with the dietary problems?’

‘I don’t think I have dietary problems,’ said Ruth, puzzled. ‘Though I’m not very fond of the insides of stomachs. Tripe is it?’

‘Miss Plackett informed us that you didn’t eat pork. It is very foolish to suppose that anyone would make you eat what you don’t want. And anyway you could have had an omelette.’

She knelt down and began to clear a patch of earth for her bulbs, and Ruth knelt down beside her to help.

‘But I like pork very much. We often had it in Vienna — my mother does it with caraway seeds and redcurrant jelly; it’s one of her best dishes.’

Miss Somerville tugged at a tuft of couch grass. ‘I thought you were a Jewish refugee,’ she said, a touch of weariness in her voice, for she could see again that life was not going to be simple; that it was the blond cowman all over again.

‘Yes, I suppose I am. Well, I’m five-eighths Jewish or perhaps three-quarters — we don’t know for certain because of Esther Olivares who may have been Jewish but may have been Spanish because she came from Valencia and was always painted in a shawl which could have been a prayer shawl but it could have been one that she wore to bull fights. But my mother was a Catholic and we’ve never been kosher.’ She pulled up a mare’s-tail and threw it onto the pile of weeds. ‘It’s a bit of a muddle, I’m afraid — the poor rabbi in Belsize Park gets quite cross: all these people being persecuted who don’t even know when Yom Kippur is or how to say kaddish. He doesn’t think we deserve to be persecuted.’ She turned to Aunt Frances: ‘Would you like me to stop talking? Because I can. I have to concentrate, but it’s possible.’

Miss Somerville said she didn’t mind one way or another and passed her the bag of bonemeal.

‘I just can’t believe this garden! I used to think that when I went to heaven I’d want to find a great orchestra like you see it from the Grand Circle of a concert hall — all the russet-coloured violins and the silver flutes and a beautiful lady harpist plucking the strings. But then when I came here I thought it had to be the sea. Only now I don’t know… there can’t be anything better than this garden. Whoever made it must have been so good!’

‘Yes. She was a Quaker.’

‘Gardeners are never wicked, are they?’ said Ruth. ‘Obstinate and grumpy and wanting to be alone, but not wicked. Oh, look at that creeper! I’ve always loved October so much, haven’t you? I can see why it’s called the Month of the Angels. Shall I go and fetch a wheelbarrow?’

‘Yes, it’s over there behind the summerhouse. And bring a watering can.’

Ruth disappeared. Minutes passed; then there was a cry. Displeased, and for a moment fearful, Miss Somerville rose.

Ruth was kneeling down by a patch of mauve flowers which had gone wild in the grass behind the shed. Flowers like slender goblets growing without leaves so that their uncluttered petals opened to the sky and their golden centres mirrored the sun. She was kneeling and she was worshipping — and Miss Somerville, made nervous by what was obviously going to be more emotion, said sharply: ‘What’s the matter? They’re just autumn crocus. I put some in a few years ago and they’ve spread.’

‘Yes, I know. I know they’re autumn crocus.’ She looked up, pushing her hair off her forehead, and it was as Miss Somerville had feared; there were tears in her eyes. ‘We used to wait for them every year before we left the mountains. There were meadows of them above the Grundlsee and it meant… the marvellousness of summer but also that it was time to leave. Things that flower without their leaves… they come out so pure. I never thought I’d find them here by the sea. Oh, if only Uncle Mishak was here. If only he could see them.’

She rose, but it was hard for her to pick up the handle of the barrow, to turn her back on the flowers.

‘Who’s Uncle Mishak?’

‘He’s my great-uncle… he loves gardening. He’s managed to make a garden even in Belsize Park and that isn’t easy.’

‘No, I imagine not. A dreadful place.’

‘Yes, but it’s friendly. He’s cleared quite a patch, and now he’s trying to grow vegetables for my mother… We can’t get fertilizer but —’

‘Why on earth not? Surely they sell it there?’

‘Yes, but we can’t afford it. Only it doesn’t matter — we use washing-up water and things like that. But oh, if he saw these! They were Marianne’s favourite flowers. It was the wild flowers she loved. She died when I was six but I can remember her standing on the alp and just looking. Most of us ran about and shrieked about how lovely they were, but Marianne and Mishak — they just looked.’

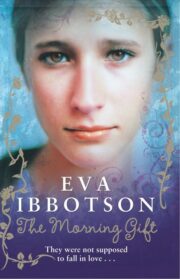

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.