The resulting conversation was as informed and intelligent as might have been expected, and when Verena turned to the women, they found her most understanding and sympathetic about their complaints. For as might have been expected, the refugees that Quin had wished on them were continuing to be ungrateful and difficult. Ann Rothley’s dismissed cowman had been taken on by the Northern Opera Company and caused havoc among the servants.

‘They’re all asking for time off to go to Newcastle and hear him sing in that ridiculous opera — the one where they burn a manuscript to keep warm. Something about Bohemians.’

And Helen’s chauffeur too was giving trouble: he was threatening to leave and go to London to try and join a string quartet.

‘Well if he does at least you won’t have to listen to all that chamber music,’ said Frances.

But, of course, it wasn’t so simple — it never is.

‘Actually, he’s rather good at his job,’ said Helen, ‘and much cheaper than an Englishman would be.’

Only with Bobo Bainbridge did Verena not attempt to converse. Bobo, whose adored husband had dropped dead nine months ago and whose mother-in-law did not approve of displays of grief, now navigated through her social engagements by means of liberal doses of Amontillado, and for women who let themselves go in this way, Verena had nothing but contempt.

At nine o’clock, Quin took the men to smoke and play billiards in the library and the women were left to discuss Verena’s party.

This, somewhat to Frances’ dismay, soon grew into a much larger affair than she had intended. Her suggestion of a buffet supper and dancing to the gramophone caused Lady Plackett considerable surprise.

‘The gramophone?’ she said in offended tones. ‘If it is a matter of expense…’

‘No, of course it isn’t,’ interrupted Ann Rothley, rather put out by this gaffe, ‘but actually, Frances, there’s a very good little three-piece band just starting up in Rothley — it would be a kindness to give them work.’

So the three-piece band was agreed on, and Helen Stanton-Derby (over-ruling Lady Plackett’s suggestion of lilies and stephanotis from the florist in Alnwick) said she would do the flowers. ‘There’s such lovely stuff in the hedges now — traveller’s joy and rosehips… with only a little help from the gardens one can make a marvellous show.’

‘And I thought mulled wine,’ said Frances. ‘Cook has an excellent recipe.’

Mulled wine, however, affected Lady Plackett as adversely as the gramophone had done and she asked if she could contribute to a case of champagne, an offer which Miss Somerville refused. ‘I’ll speak to Quin,’ she said firmly; ‘he’s in charge of the cellar,’ and they went on to discuss the menu and the list of guests.

Comments on Verena, as the County drove home, were entirely favourable.

‘A very sensible girl,’ said Ann Rothley and her husband grunted assent, but said he was surprised that Quin, who’d had such beautiful girlfriends, was willing to marry somebody who, when all was said and done, looked like a Roman senator.

His wife disagreed. ‘She has great presence. All she needs is a really pretty dress for the dance and she’ll be as attractive as anyone could wish.’

An unexpected voice now spoke from the back of the motor where Bobo Bainbridge had been supposed to be asleep.

‘It will have to be a very pretty dress,’ said Bobo — and closed her eyes once more.

Frances, meanwhile, had followed Quin into the tower — a thing she did seldom — to ask his advice about the drinks.

‘Ah yes, Verena’s dance.’ Quin had taken so little notice of discussions about this event that it took an effort to recall it. ‘It’s on Friday week, isn’t it? Does Verena want me to look in or would she prefer to entertain her friends on her own?’

Frances looked at him in dismay. ‘But of course she wants you to be there. It would look very odd if you weren’t.’ And then: ‘You do like Verena, don’t you?’

‘She’s an excellent girl,’ said Quin absently. And then: ‘Who have you invited?’

‘Rollo’s coming up from Sandhurst — he won the Sword of Honour, did Ann tell you? And he’s bringing a friend of his who’s going to join the same regiment. And the Bainbridge twins have got leave from the air force so —’

‘From the air force? Mick and Leo? But they can’t be more than sixteen!’

‘They’re eighteen, actually — they went in as cadets. Bobo was hoping one of them would stay on the ground, but they’ve always done things together; they’re both fully fledged pilots now.’

‘My God!’ Bobo’s adored twins had kept her alive after her husband’s death. When they came home, she sobered up, became the friendly, funny person she had been throughout his childhood.

‘And both Helen’s girls are coming up from London. Caroline’s going to marry that nice red-haired boy in the Marines — Dick Alleson.’ Caroline had carried a torch for Quin for many years and everyone had rejoiced when she became so suitably engaged.

She went on counting off the guests and Quin looked out over the silvered sea. It might not come — the war — but if it did, there was not one of those gilded youths but would be in the thick of the slaughter.

‘I know what we’ll drink, Aunt Frances!’ he said, taking her hands. ‘The Veuve Clicquot ’29! I’ve got two cases of it and I’ve been saving it for something special.’

Frances stared at him. She was no connoisseur of wine but she knew how Quin prized his fabulous champagne. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Why not? Let’s make it a night to remember!’

Frances went to bed a happy woman, for what could this open-handed gesture mean except that he wished to honour Verena? But the next morning came the remark she had been dreading.

‘If there’s a party of young people, we must ask the students if they’d like to come along.’

Gloom descended on Aunt Frances. Jewish waitresses, girls who did things in the backs of motor cars, to mingle with the decently brought up children of her friends.

‘They’re coming to lunch on Sunday. Surely that’s enough?’

Quin, however, was adamant. ‘I can’t single Verena out to that degree, Aunt Frances, you must see that.’

But to Frances’ great surprise, Verena entirely agreed with Quin and offered herself to invite the students.

She was as good as her word. Arriving at the boat-house while everyone was still at breakfast, she said: ‘There’s going to be a dance up at Bowmont for my birthday. Anyone who wouldn’t feel uncomfortable without the proper evening clothes would be entirely welcome.’

By the time Quin appeared to begin the morning’s work, she was able to tell him with perfect truth that the students had refused to a man.

Chapter 19

‘But why? Why won’t you come? Everyone is invited — all the students go to Sunday lunch at Bowmont. It’s a ritual.’

‘Well, it’ll be just as much of a ritual without me. I’m waiting for a message from Heini and —’

‘Not on a Sunday. The post office is shut.’

The other students joined in, even Dr Elke — but Ruth was adamant. She didn’t feel like a big lunch, she was going for a walk; she thought the weather might be breaking.

‘Then I’ll stay with you,’ said Pilly, but this Ruth would not hear of and Pilly was not too hard to persuade, for the thought of sitting in a well-upholstered chair and eating a substantial Sunday lunch was very attractive.

It was very quiet when the others had gone. For a while, Ruth wandered along the shore, watching the seals out in the bay. Then suddenly she turned inland, taking not the steep cliff path that led up to the terrace, but the lane that meandered between copses of hazel and alder, to join, at last, the drive behind the house.

She had been along here before on the way to the farm and now she savoured again the rich, moist smells as the earth took over from the sea. She could still hear the ocean, but here in the shelter were hedgerows tangled with rosehips and wild clematis; sloes hung from the bushes; and the crimson berries of whitebeam glinted among the trees.

After a while the lane looped back, passing between open farmland where freshly laundered sheep grazed in the meadows and she leant over the fence to speak to them, but these were not melancholy captives in basements, but free spirits who only looked up briefly before they resumed their munching.

She was close to the house now, but hidden from it by a coppice of larches. If she turned into the drive she would reach the lawns and the shrubberies on the landward side. The students had been told they could go where they wanted, and Ruth, who could not face Verena lording it over Quin’s dining table, still found that she was curious about his home.

Crossing the bridge over the ha-ha, she came to a lichen-covered wall running beside a gravel path — and in it, a faded blue door framed in the branches of a guelder-rose. For a moment, she hesitated — but the grounds were deserted, no sound came to break the Sunday silence — and boldly she pushed open the door and went inside.

‘I expect it’s the dietary laws,’ said Verena reassuringly to Aunt Frances. ‘She is a Jew, you know, from Vienna. Perhaps she expects that we shall be eating pork!’ And she laughed merrily at the oddness of foreigners.

Pilly and Sam, sipping sherry in the drawing room, looked angrily at Verena.

‘Ruth doesn’t fuss at all about what she eats, you know that — and anyway she was brought up as a Catholic.’

But this was not a very promising defence for no one knew now what excuse to make for Ruth. Aunt Frances, however, accepted the kosher version of events, remarking that it had been the same with the cowman Lady Rothley had employed in the dairy. ‘We could have given her something else, I suppose. An omelette. But there is always the problem of the utensils.’

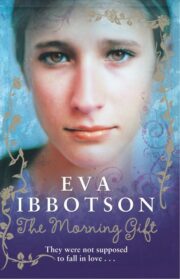

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.