‘You think I should invite her then?’

‘Yes, I do. And more than that. I think we should put our shoulders to the wheel. I think we should rally round and really welcome the girl. If it’s her birthday during the time she’s here why don’t you give a party for her, or a small dance? I know you don’t care for all that, but we’ll help you. Rollo’s coming up next week with a friend from Sandhurst and Helen’s girls are home. Nothing formal, of course, but it’s years since Quin’s seen his home en fête — and with the students here he can’t run away like he sometimes does!’

Frances, quailing at the thought of so much sociability, now had another unpleasant thought. ‘You don’t think he’ll expect the students to come? The ones down at the boathouse, I mean?’

‘I shouldn’t think so. Quin may be democratic, but he knows how things are done.’ And coming over to lay her arm round Miss Somerville’s shoulder in a rare gesture of affection: ‘This may be what we’ve been waiting for, Frances. Let’s give the girl a chance.’

Miss Somerville returned to Bowmont as a woman with a mission. The letter she wrote to Lady Plackett was cordial in the extreme, and the instructions she gave to Turton were explicit.

‘We’re having house guests next week — a Miss Plackett, one of the Professor’s students. I want the Tapestry Room prepared for her, and the Blue Room for her mother. And there’ll be a small party on the 28th which is Miss Plackett’s birthday.’

Turton might be discreet, but the girls who prepared the Tapestry Room for Verena were not and nor was the cook, told to expect twenty or so young people for supper and dancing. And soon it had spread to all the servants’ halls in North Northumberland that Quinton Somerville was expecting a very special young lady and that wedding bells were in the air at last.

And as below stairs, so above. Ann Rothley was as good as her word. She telephoned Helen Stanton-Derby, still suffering from the violin-playing chauffeur that Quin had wished on her, and Christine Packham over in Hexham and Bobo Bainbridge down in Newcastle — and all of them, even those with marriageable daughters who would have done very well as mistress of Bowmont, promised to welcome Verena Plackett whose mother was a Croft-Ellis and who would, if she married dear Quin, scotch once and for all this nonsense about giving his home away. Not only that, but they unhesitatingly offered their offspring for Verena’s party, for the knowledge that Quin had seen his duty at last made everyone extremely happy.

As for Lady Plackett, receiving a reply of such unexpected cordiality, she decided to accompany Verena herself and stay for a few days at Bowmont, returning for Verena’s actual party.

‘But I think, dear,’ she said to her gratified daughter, ‘that it might be best to say nothing about the invitation till just before we go. There could be jealousy and ill-feeling among the students — and you know how concerned dear Quinton is about any apparent favouritism.’

Verena thought this was sensible. ‘We will leave Miss Somerville to acquaint him,’ she said, and returned to her books.

And Frances did, of course, write to Quin and tell him what she had done, but the week before the students were due to leave, a Yorkshire quarryman turned up a leg bone whose size and weight caused pandemonium in the local Department of Antiquities. Answering a plea to authenticate the find and halt work in the gravel pit, Quin rearranged his lectures and drove north. Delayed by the importance of the discovery — for the bone turned out to be the femur of an unusually complete mammoth skeleton — and involved in a bloodthirsty battle with a rapacious contractor, Quin decided not to return to town, but make his way straight to Bowmont.

His aunt’s letter thus remained unopened in his Chelsea flat.

It was the day after Quin left for Yorkshire that Ruth received the confirmation she had been longing for. Heini had booked his ticket, he was coming on 2 November and in an aeroplane!

‘So no one will be able to take him off!’ said Ruth with shining eyes.

‘I can’t believe I’m really going to see him,’ said Pilly.

‘Well you are — and you’re going to hear him too!’

For now, of course, what mattered more than anything was to secure the piano. Ruth was only five shillings short of the sum she needed, and as though the gods knew there was no more time to waste, they sent, that very night, a young man named Martin Hoyle in to the Willow Tea Rooms.

Hoyle lived in a villa on Hampstead Hill with his mother and had independent means, but it was his ambition to be a journalist and he had already submitted a number of articles to newspapers and magazines, not all of which had been refused. Now he had had an idea which he was sure would further his career. He would extract from the refugees who had colonized the Willow, their recollections of Vienna; poignant anecdotes of the pomp and splendour of the Imperial City, or more recent ones of the Vienna of Wittgenstein and Freud. Not only that, but Mr Hoyle had an angle. He was going to contrast the rich stock of memories which they carried in their heads with the meagre contents of the actual luggage they had been allowed to bring. ‘Suitcases of the Mind’ was to be the title of the piece which he was sure he could sell to the News Chronicle or even to The Times.

He had come early. Though Ziller, Dr Levy and von Hofmann — all Viennese born and bred — were talking together by the window, it was Mrs Weiss, sitting alone by the hat stand, who accosted him.

‘I buy you a cake?’ she suggested.

To her surprise, the young man nodded.

‘Thank you,’ he said, ‘but let me buy you one.’

Mrs Weiss did not object to this so long as he sat down and let her talk to him. Two slices of guggle were brought, and Mr Hoyle introduced himself.

‘I was wondering if you would mind if we talked a little about your past? Your memories?’ said Mr Hoyle. ‘You see, I was once in Vienna; it was a city I loved so much.’

Mrs Weiss’s eyes flickered. She had never actually been in Vienna, which was a long way from East Prussia and her native city of Prez, but if she admitted this, Mr Hoyle would go away and talk to the men by the window, whereas if she played her cards right, she could keep him at her table and when her daughter-in-law came to fetch her, she would see her in conversation with a good-looking young man.

‘Vat is it you vant me to remember?’ she enquired.

‘Well, for example, did you ever see the Kaiser? Driving out of the gates of the Hofburg, perhaps?’

A somewhat frustrating quarter of an hour followed. In lieu of the Kaiser, Mr Hoyle received the old lady’s low opinion of mutton chop whiskers; instead of famous premieres at the opera, he learnt of the laryngeal problems which had prevented her nephew, Zolly Federmann, from taking to the stage.

‘But the Prater?’ asked Mr Hoyle, growing a little desperate. ‘Surely you must have bowled your hoop along the famous chestnut alley?’

Mrs Weiss had not, but described a rubber crocodile on a string, of which she had been very fond till some rough boys from an orphanage had punctured it.

‘Well, what about the Giant Wheel, then?’ Mr Hoyle wiped his brow. ‘Surely you remember riding on that? Or the paddle boats on the Danube?’

It was at this point that Ruth entered, ready to begin the evening’s work, and smiled at the old lady. To the men, Mrs Weiss would not have ceded the young journalist, but Ruth was different. Ruth was her friend. She became suddenly exasperated.

‘I haf not been on the wheel in the Prater. I haf not been on the Danube in the paddling boat. I haf not seen Franz Josef coming from gates, and I do not remember Vienna because I haf never been in Vienna. I have been only in Prez and once to the fur sales in Berlin, but was cheated. So now please go away for I am only a poor old woman and my daughter-in-law makes me sleep in wet air and it should be better for everybody that I am dead.’

Needless to say, this outburst, clearly audible throughout the café, brought help from all sides. While Ziller and Dr Levy consoled the shaken Mr Hoyle, Ruth comforted the old lady — and Miss Maud and Miss Violet agreed that under the circumstances (and because Mr Hoyle’s article, if published, might be good for trade) two tables could be pushed together.

And soon Mr Hoyle’s notebook began to fill up with useful anecdotes. Dr Levy told how he had assisted with the removal of an anchovy from the back of the Archduke Otto’s throat; Paul Ziller described being hit by a tomato during the premiere of Schönberg’s Verklärte Nacht and von Hofmann recounted the classic story of Tosca bouncing back from a too tightly stretched trampoline after her suicidal leap from the ramparts.

But it was at the Willow’s waitress, as she too shared her memories, that Mr Hoyle looked most eagerly, for he knew now what was missing from his story. Love was what was missing. Love and youth and a central theme. A young girl waiting for her man, working for him. Who wanted suitcases when all was said and done? Love was what they wanted. Love in the Willow Tea Rooms… Love in Vienna and Belsize Park. If only she would talk to him, he would sell his story, he was sure of that.

And Ruth did talk to him; talking about Heini was her pleasure and delight. As she whisked between the tables with her tray, she told him of Heini’s triumphs at the Conservatoire and how he had been inspired, in the meadow above the Grundlsee, to write an Alpine étude. He learnt of Heini’s passion for Maroni, the sweet chestnuts roasted everywhere on street corners in the Inner City — and that at the age of twelve he had played a Mozart concerto based on the song of a starling which surprised Mr Hoyle who had thought of starlings as raucous despoilers on the roofs of railway stations.

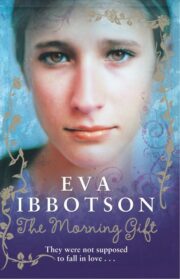

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.